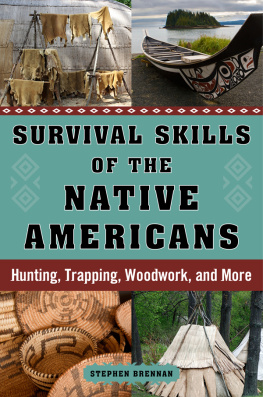

Copyright 2015 by Stephen Brennan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Jane Sheppard

Cover photos: ThinkStock

Print ISBN: 978-1-62873-709-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62914-049-0

Printed in China

CONTENTS

THE TRAPPERS BY W. F. WAGNER

T he evolution of the trapper may be traced back to the old French rgime when the coureurs des bois , rangers of the woods, or the peddlers of the wilderness, held sway. These were, however, more traders than trappers, purchasing the pelts from the Indians for trifles and frequently accompanying them on their hunting excursions. They were as profligate as their successors, and their occupation passed away with the passing of the French control of Canada and with the establishment of the interior trading-posts by the merchants of Canada, who later formed companies and conducted the business in a more systematic manner. From these interior trading-posts. traders and trappers were sent out to trade with the Indians and trap in their territory at the same time. The trading gradually fell into the hands of the trading-posts; the trapper meanwhile pursued his vocation, and it became his recognized and established business, where he remained an important factor in the fur-trade down to the time of its decline and ultimate death.

While Mr. Hunt was at Mackinaw engaging men for the Astoria venture, there arrived at this place some of these characters, and his description of them is so accurate that I take the liberty of giving it here:

A chance party of Northwesters appeared at Mackinaw from the rendezvous at Fort William. These held themselves up as the chivalry of the fur-trade. They were men of iron; proof against cold weather, hard fare, and perils of all kinds. Some would wear the Northwest button, and a formidable dirk, and assume something of a military air. They generally wore feathers in their hats, and affected the brave. Je suis un homme du nord! I am a man of the northone of these swelling fellows would exclaim, sticking his arms akimbo and ruffling by the Southwesters, whom he regarded with great contempt, as men softened by mild climates and the luxurious fare of bread and bacon, and whom he stigmatized with the inglorious name of pork-eaters. The superiority assumed by these vainglorious swaggerers was, in general, tacitly accepted. Indeed, some of them had acquired great notoriety for deeds of hardihood and courage; for the fur-trade had its heroes, whose names resounded throughout the wilderness.

The influence and part played by the trapper and free trapper in the development of our great West has had up to this time but little consideration from either the government or the people. We have given entirely too much credit to pathfinders whose paths were as well known to the above as is the city street to the pedestrian. It is true, however, that they gave to the world a more complete description and placed these secret ways of the mountains in a more correct geographical position than the uneducated trapper was able to do.

There was not a stream or rivulet from the border of Mexico to the frozen regions of the North, but what was as familiar to these mountain rangers and lonesome wanderers, as the most traveled highway in our rural districts. The incentive was neither geographical knowledge nor the honor won by making new discoveries for the use and benefit of mankind in general, but a mercenary motivethe commercial value of the harmless and inoffensive little beaver. The trappers followed the course of the various streams looking for beaver signs and had no interest whatever in any other particular. Every stream had a certain gold value if it contained this industrious little animal, and so they followed them from their source to their mouth with this one object in view. For their own comfort and convenience they observed certain landmarks and the general topography of the country, in order that they might rove from one place to another with the least labor and inconvenience. In this manner they came to have a thorough and comprehensive knowledge of the geography and topography of the great West, and were in truth the only pathfinders; but they have been robbed even of this honor to a great extent.

The life of the solitary trapper in the mountains seems unendurable to one who is fond of social intercourse or of seeing now and then one of his fellow-beings. This habit of seclusion seemed to grow on some of the men and they really loved the life on that account, with all its hardships, privations, and dangers. The free trappers formed the aristocratic class of the fur-trade, and were the most interesting people in the mountains. They were bound to no fur company and were free to go where and when they pleased. It was the height of the ordinary trappers ambition to attain such a position. They were men of bold and adventurous spirit, for none other would have had the courage to follow so dangerous an occupation. They were liable to have too much of this spirit of bravado, and frequently did extremely foolhardy things, nor could their leaders always control them in these excesses. They were exceedingly vain of their personal appearance and extravagantly fond of ornament for both themselves and their steeds, as well as their Indian wives. Indeed, they rivaled the proud Indian himself in the manner in which they bedecked themselves with these useless and cheap ornaments. They were utterly improvident, extremely fond of gambling and all games of chance, as well as all sorts of trials of skill, such as horsemanship and marksmanship; of course, the necessary wager to make it interesting was never wanting. As a general rule, the greater part of the proceeds of their labor was squandered at the first rendezvous or trading-post which they reached, and it was of great importance to the trader to be the first to reach such a rendezvous, thus securing the greater part of this most profitable trade.

Very little is known of their lonely vigils and wanderings, with a companion or two, in the defiles of the mountains, and of the dangers and privations they have had to endure. How frequently their bones have been left to bleach on the arid plains, as the result of Indian hatred and hostility, without the rites of burialtheir names, unhonored and unsung, will never be known. Certain tribes were the uncompromising enemies of the trappers, and when they had the misfortune to meet, they waged a relentless war, until one or the entire party left the country or was exterminated. It is true, the returns were sometimes enormous, and had they exercised ordinary economy, even for one season, they could have retired from the dangers and privations of the mountains with a competence; but had they done so, it is altogether likely that they would sooner or later have again fallen victim to its allurements.