When all else fails, fire is the simplest means of providing comfort and warmth against cold and wet in the Northern Forests.

If you were dressed in the old European tradition, with numerous layers of fluffy wool adequate to deal with the bitter cold, you would likely be wearing about nine kilograms or 25 pounds of clothing. If you were unable to dry your clothing out, within five days you would be carrying six kilograms more weight of accumulated frost. The efficiency of your clothing would be so impaired by this frost build up you could die of hypothermia within a week.

When you stop moving in cold weather, the first thought should be to light a fire. Your hands should not be allowed to become so numb that fire-lighting becomes difficult. A simple test of your level of physical capacity is to touch the thumb to the little finger of the same hand. The moment you have any difficulty in doing this you should light a fire.

In cold, wet weather when the need is most urgent, firelighting is often the most difficult. You may have to exercise strenuously to restore some manipulative capacity to your hands, or in your clumsiness you may drop or break matches while attempting to strike them.

The test for hypothermic incapacity. If you cannot touch your thumb to your little finger, you should take immediate steps to warm up.

FIRE-LIGHTING

There are four basic stages in fire-lighting:

1. Ignition. Fire may be started in a variety of ways. The most common methods are matches, the flint and steel, and the bow drill.

2. Establishment. This stage involves using the most effective method to light the required type of fire with the fuel available. Fine and coarse kindlings are ignited, which in turn ignite sufficient fuel of the right quality so the fire will continue to burn even in wind or rain. Establishment is a critical aspect of fire-lighting under adverse conditions as there are often many problems to overcome.

3. Application. There are a number of different fire arrangements that produce the best desired effect, combined with the special properties of the fuels available. There are fires for cooking, warming, drying, repelling insects, signaling and so on.

Maintenance and Moderation. A fire can be made to burn at a desired output with a minimum of smoke. Knowledgeable maintenance will allow you long periods between adjustments or stokings.

In a stove, a fine kindling is set on fire (ignition) which in turn ignites coarse kindling, and then a fuel that burns fairly hot (establishment). The fuel should produce a good bed of coals to better utilize a slower burning, perhaps green fuel, for staying power. If the fire is too hot, green fuel may be added or the air supply restricted (moderation). An open fire, being fuel regulated, is more complex to control than one in a stove but the stages remain the same.

IGNITION

Matches

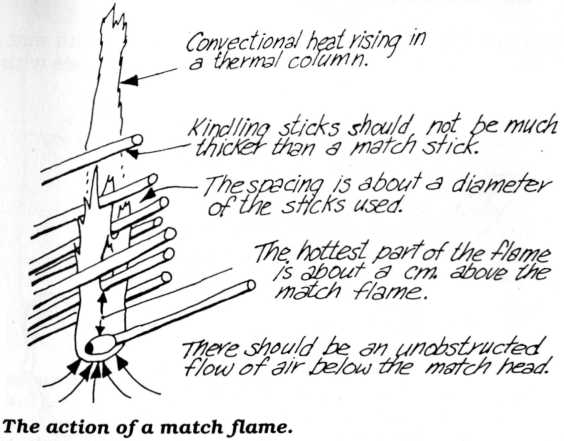

The most common and convenient way to light a fire is, understandably, to use a match. The match flame should be instantly transferred to a combustible material while taking care to protect the flame from any wind. Open-flame methods of ignition are vulnerable to air movements that tend to extinguish a flame while it is small, but help intensify it when it is large.

The larger the match, the more time there is to transfer the flame to any kindling, and the better the chance the flame will catch. For example, a large kitchen match will burn for at least the count of 40, one of paper for 15, and a split paper match for five. If you consistently succeed with a split paper match in wet, windy weather, you should never have a problem lighting fires in the bush.

Matches should be carried in waterproof containers in three separate places. First, in your pants pocket (assuming your pants are the last items of clothing to be removed). A second back-up container should be carried elsewhere, possibly in your shirt pocket. The third is a reserve in your pack to replenish the other two sources.

Unprotected matches are ruined by sweat, melted frost build-up in the clothes, rain or from falling into water. A match container should be tested by submersion for ten minutes. The container must be easy to open with wet or numb hands.

Matches should never be carried loose in any pocket. Every year thousands of North Americans suffer severe burns from this habit, with over 50 actually burning to death.

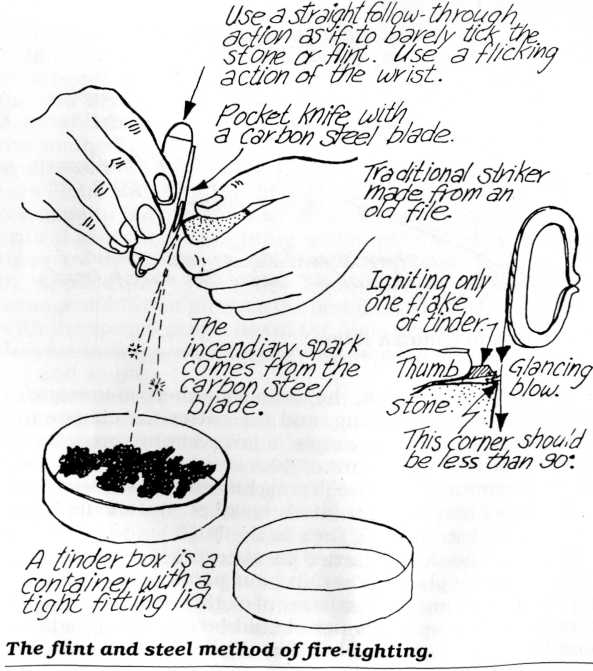

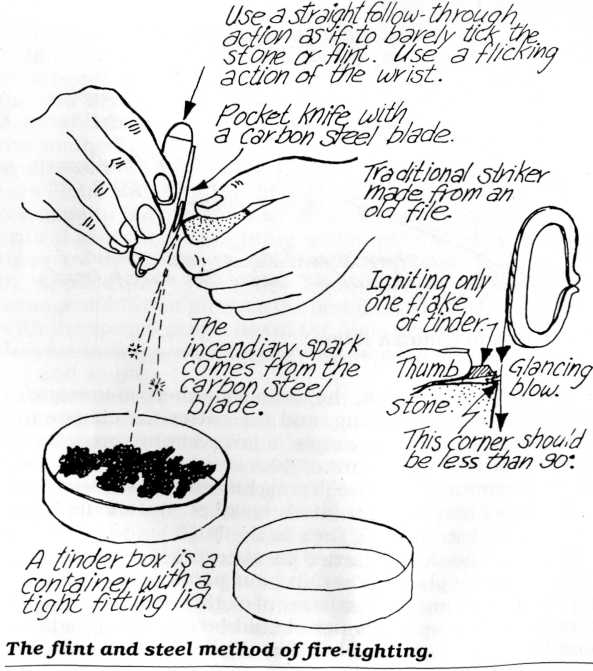

The Flint and Steel

Wind is a major problem when lighting a fire with matches. On the other hand, the flint and steel dispenses with an open flame and uses wind to advantage. Though not as convenient, it is a superior method under all adverse conditions. When you are down to your last ten matches you may choose to conserve them by converting to the flint and steel.

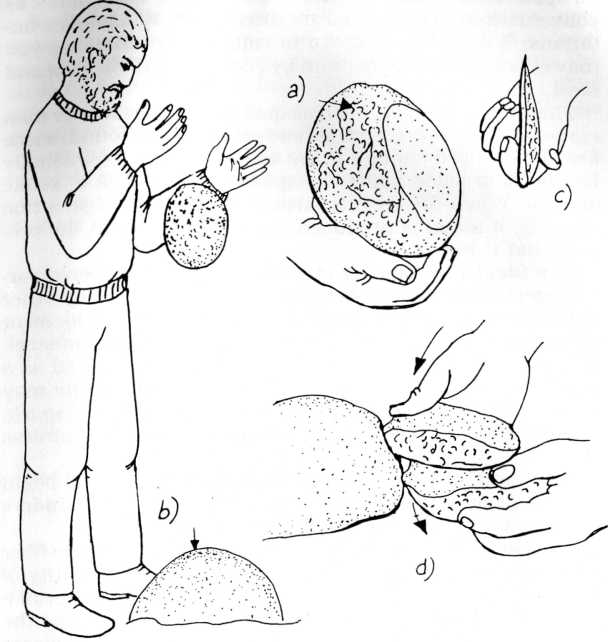

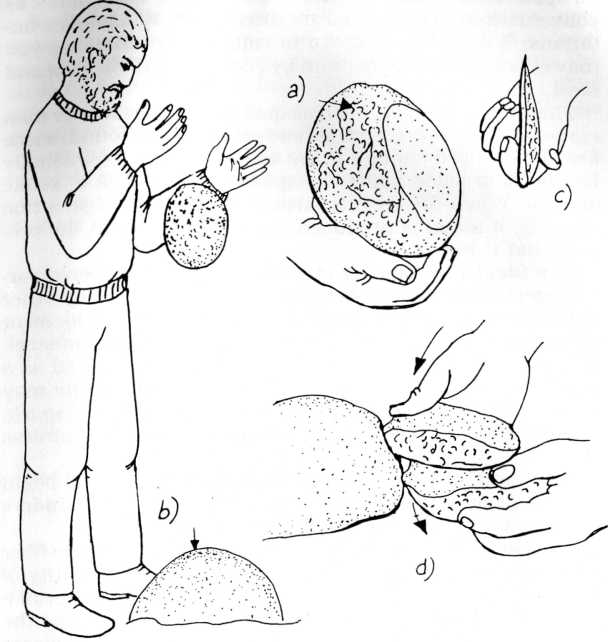

Method of cracking apart a rock to expose a striking surface.

a) Identifying quartzite. Quartzite is a commonly found hard rock that makes a good flint. The best rock displays a surface marked with many crescent-shaped fractures.

b) Cracking a quartzite boulder. Quartzite boulders that are either flat or discus-like are easily cracked when dropped on a larger rock. Spherical or egg-shaped rocks are very tenacious, tending to bounce rather than crack. Rocks that must be thrown to be broken are dangerous and may rebound towards you or the flying shards may cause injury.

c) A quartzite flake. A flake that is knocked off a quartzite boulder is usually sharp enough to be used as a chopper or saw for working wood or as a knife for skinning.

d) Breaking quartzite into small pieces. Once a quartzite boulder is broken in half it is easily fractured into smaller pieces that are more suitable for use as flints. The flints should have sharp edges that can be struck with the steel.

The Flint. Any rock, such as quartzite, that is harder than carbon steel can be used. Wherever rocks are found, some are always hard enough to act as a flint. The rock usually has to be cracked apart to expose a sharp edge to strike against. When the steel is struck against this edge, a fine shaving of metal is produced becoming so hot in the process that it burns.

The Steel. The steel or striker must be of tempered carbon steel to obtain the best sparks. Although many other substances may work, few have the intense fiery focus or incendiary spark like a burning fragment of carbon steel. A natural stone, known as iron pyrite, may be used as a striker or both striker and flint. Two pieces of pyrite may be struck against each other to obtain an incendiary spark. It is difficult to produce sparks from pure iron or stainless steel.

The Tinder

Tinder is a special material that will begin to glow from an incendiary spark. There are three tinders commonly used in the Northern Forests.

1. Synthetic Tinder. Made by charring any vegetable fiber such as cotton, linen or jute. To make a small quantity of cloth tinder, tear out ten strips of old blue jean material a few centimetres wide and 20 centimetres long. Drape the strips across a stick and set the material on fire. As the flame dies down stuff the burning mass into an airtight container. Once the flame subsides and the charred material begins to glow, the lid is put on to exclude oxygen. If no airtight tin or tinderbox is available, two pieces of bark can be used. To make larger quantities tightly roll up and bind a jeans pant leg with wire. Build a fire over the bundle. When it dies down, stuff the glowing mass of cotton into a jam can with a tight-fitting lid.