CONTENTS

Seven Myths of

Native American History

M YTHS OF H ISTORY : A H ACKETT S ERIES

Seven Myths of

Native American History

by Paul Jentz

Series Editors

Alfred J. Andrea and Andrew Holt

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2018 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Rick Todhunter and Brian Rak

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jentz, Paul, author.

Title: Myths of history : seven myths of Native American history / by Paul Jentz.

Description: Indianapolis, Indiana : Hackett Publishing Company, 2018. | Series: Myths of history series; v. 4 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017040028| ISBN 9781624666780 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781624666797 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Indians in popular cultureUnited States. | Indians of North AmericaPublic opinion. | Indians of North AmericaHistoriography. | Stereotypes (Social psychology) | Public opinionUnited States.

Classification: LCC E98.P99 J46 2018 | DDC 970.004/97dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017040028

ePub3 ISBN: 978-1-62466-719-0

Seven Myths of the Crusades . Edited, with an Introduction and Epilogue, by Alfred J. Andrea and Andrew Holt.

Seven Myths of the Civil War . Edited, with an Introduction, by Wesley Moody.

David Northrup, Seven Myths of Africa in World History .

C ONTENTS

The page numbers in curly braces {} correspond to the print edition of this title.

{vii}

It is with great pleasure that we introduce the fourth volume in Hackett Publishing Companys Myths of History Series, Seven Myths of Native American History by Paul Jentz.

The history of the Indians of North America is long and complex, especially when one puts aside stereotypical images of who they were and are and what constitutes Indian culture. Moreover, the story of their relations with the colonists and settlers of the lands that became the United States and Canada often makes for uncomfortable reading. Beyond that, it is a subject that continues to be bitterly fought over by partisans and scholars on all sides of its many issues. It speaks well of Jentzs devotion to this, his chosen field of historical inquiry, that he has undertaken the challenge of subjecting to analysis seven of the most common misperceptions of the Native Americans who have occupied the lands north of the Rio Grande for thousands of years and continue to reside in numerous sovereign nations and singular communities across this vast expanse.

On a Sunday walk not too long ago, one of the series editors happened across this memorial along the Beacon Street boundary of the Boston Common. It is a memorial he had often noticed but, until that moment, had never viewed in any meaningful way. Sculpted in bronze relief by John Francis Paramino, it was set in place in 1930 to commemorate the founding of Boston three hundred years earlier. Depicted on it is William Blackstone, the areas first White resident, greeting colonial governor John Winthrop and his company of English settlers. Behind Winthrop stand John Wilson, Bostons first Puritan minister, holding a bible, and Ann Pollard, Bostons first White woman (who is incorrectly portrayed as an adolescent). Behind Blackstone, at the far edge of the relief, are two almost totally naked Native Americans, who look on rather impassively. They have emerged from the nearby forest but seem simultaneously to recede back into that environment.

Employing the myths that Jentz deconstructs, what can we say about the First Americans who are portrayed here? Well, they are certainly marginalized, both physically and symbolically. Three large White men dominate the foreground. The two Indians are dwarfed, one by stature (the Indian closer to us), the other by posture (the kneeling Indian). This disproportion seems to be more than accidental. The Indians seem to be little more than a scale against which the newly arrived colonists are measured. Moreover, as they gaze upon the almost larger-than-life Englishmen, who carry to these shores Legitimate Government and True Religion, the two Indians are passive agents in an otherwise active scene. Are they even capable of benefiting from these dual blessings of civilization? It seems unlikely. As we learn in Chapter 4, they {viii} are symbolically and collectively the Vanishing Indian. To be sure, the sculptor has demonstrated his technical skill by investing them with muscular bodies and noble features, thereby making them Noble Savages, the subject of Chapter 1. But the salt marsh and forest that Paramino shows us, and into which the Indians blend, is largely an empty wilderness ready to be populated by a Christian Chosen People (Chapter 3).

Founders Memorial, celebrating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Boston, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of A. J. Andrea, 2017.

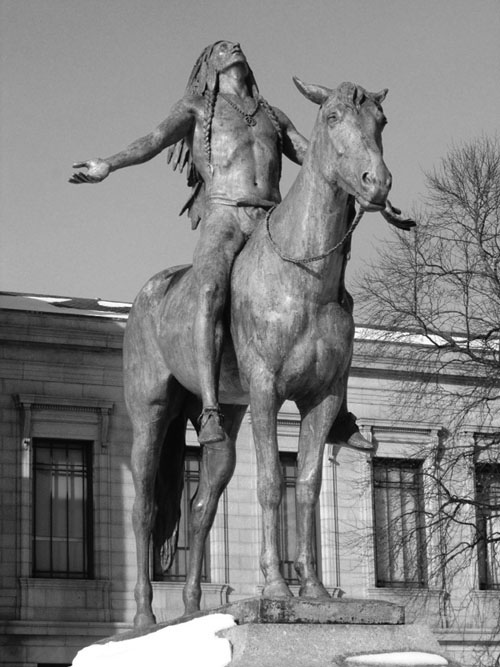

About two miles from Boston Common is the Museum of Fine Arts. At its main entrance stands an imposing equestrian statue known as Appeal to the Great Spirit. Created in 1909 by Cyrus E. Dallin, it was the last of his four-part Epic of the Indian series of bronze sculptures and was immediately recognized as the best of the four. Indeed, of his more than 260 sculptures, Appeal to the Great Spirit is his most highly regarded and even beloved work. Smaller-sized replicas of it can be found across the United States and beyond, including a twenty-one-inch statuette in the White House that once graced the Oval Office of President Clinton. Dallin, a native of Utah, admired the culture of the Plains Indians and surely intended this, and the other three sculptures in the series, as a tribute to the horse-riding Native Americans of North America. Yet, once again employing Jentzs insights, one can perceive certain disturbing features in this work of art.

In harmony with Chapter 5, one asks, Who is the Authentic Indian? The model for the man on horseback was Antonio Corsi, an Italiananother example of the {ix} propensity of impresarios and artists of that era to present White men in redface. Beyond that, we might well ask, was Dallins homage to a people he respected an inadvertent exercise in perpetuating the myth of the Noble Savagea myth that, regardless of the honorable intentions behind it, robs Native Americans of their full humanity? Even more so, was Dallin a devotee of another mythic view of Native American culture that was already popular in the early twentieth century, the Mystical Indian, the topic of Chapter 7? These are vexing questions and just two of many that Jentzs penetrating study forces us to confront. And there are no easy answers to them.

Appeal to the Great Spirit, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo courtesy of A. J. Andrea, 2017.

{x} Certainly, we are not indicting the city of Boston or its Museum of Fine Arts with the charge of gross ethnic insensitivity. Attitudes and perspectives have changed substantially in that city since 1930, and the MFAs collection of pre- and post-Columbian Native American artifacts is sensitively curated, interpreted, and displayed. Furthermore, there is nothing uniquely Bostonian about these sculptures. Similar, often well-intentioned representations of Native Americans can be found today in almost any city in the United States. It is no exaggeration to say that such subtle (and not-so-subtle) images and the notions that underscore them remain part of our cultural baggage.