THE HISTORY OF COMMUNICATION

Robert W. McChesney and John C. Nerone, editors

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

2016 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Coward, John M.

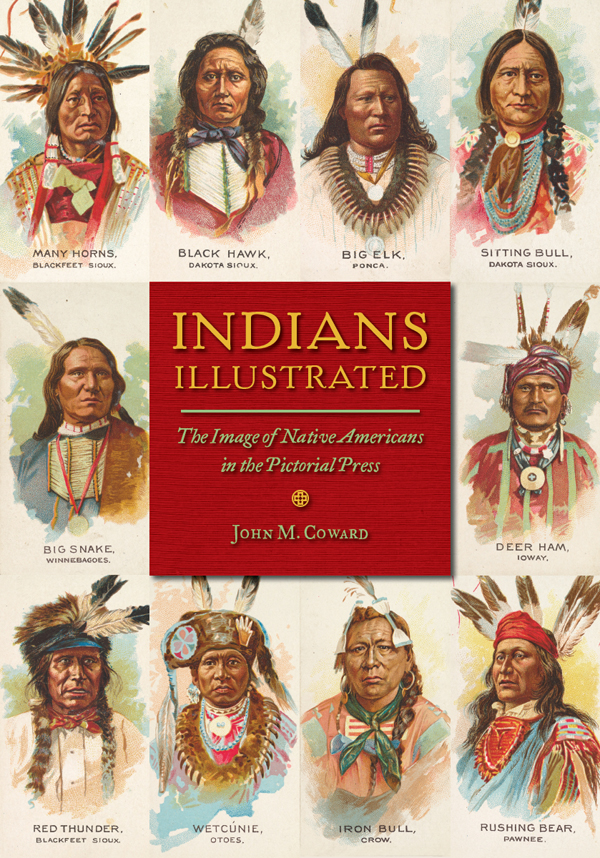

Title: Indians illustrated: the image of Native Americans in the pictorial press / John M. Coward.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2016. | Series: The history of communication | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015046831 (print) | LCCN 2016011529 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252040269 (cloth : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780252081712 (paperback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780252098529 | ISBN 9780252098529 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Indians of North AmericaPress coverageHistory. | Indians of North AmericaPublic opinionHistory. | Illustrated periodicalsUnited StatesHistory. | Journalism, PictorialSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | Visual communicationUnited StatesHistory. | Stereotypes (Social psychology)United StatesHistory. | Indians in popular cultureUnited StatesHistory. | Public opinionUnited StatesHistory. | Popular cultureUnited StatesHistory. | United StatesRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC PN4888.I52 C67 2016 (print) | LCC PN4888.I52 (ebook) | DDC 070.4/4997000497dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015046831

Acknowledgments

This book took shape over many years of reading, researching, and writingas well as a great deal of rewriting and revision. I was assisted along this path by friends and colleagues at the University of Tulsa and in the larger community of journalism and media historians I have been fortunate to know. First, I want to acknowledge the support of my colleagues at the TU Faculty of Communication, Joli Jensen, Mark Brewin, and Ben Peters. I have also been encouraged over the years by TU colleagues in other departments, including Brian Hosmer from history and Garrick Bailey from anthropology. My work as a journalism historian has been enriched by my friends in the American Journalism Historians Association (AJHA) and the History Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC). In particular, I thank William E. Huntzicker for his generous spirit and long-standing support of my research on Native Americans and the nineteenth-century press. I also want to thank the editors and reviewers of scholarly journals where parts of this book were first published, including Pat Washburn of Journalism History, Barbara Friedman and Kathy Roberts Ford of American Journalism, and Berkley Hudson of Visual Communication Quarterly.

For research support and access to collections, I am grateful to American Antiquarian Society and The American Historical Print Collectors Society Fellowship for research time in the AAS collection. Paul Erickson, director of academic programs at AAS, was especially helpful in making me feel at home at that outstanding research library. I also received generous support from the American Journalism Historians Association through the Joseph McKerns Award, which supported research in the collections of at the New-York Historical Society. In support of the publication of this book, I thank the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs at the University of Tulsa for their generous assistance. I also want to thank the staff at the University of Illinois Press, especially Daniel Nasset, for their support of this project.

On a more personal note, I am grateful for the love and support of my children, Ian and Rachel, and my life-long partner and best friend, Linda, without whom I could not have completed this project. Finally, I dedicate this book to my mother, Loretta Mason Coward (Carson-Newman College, Class of 1948), who grew up in an old Cherokee town in the southeast corner of Tennessee known today as Ducktown. She provided the example of hard work and stick-to-itiveness that shaped me during my childhood and adolescence, lessons that carried over into my scholarly life. I am a better person because of her love.

Introduction

Illustrating Indians in the Pictorial Press

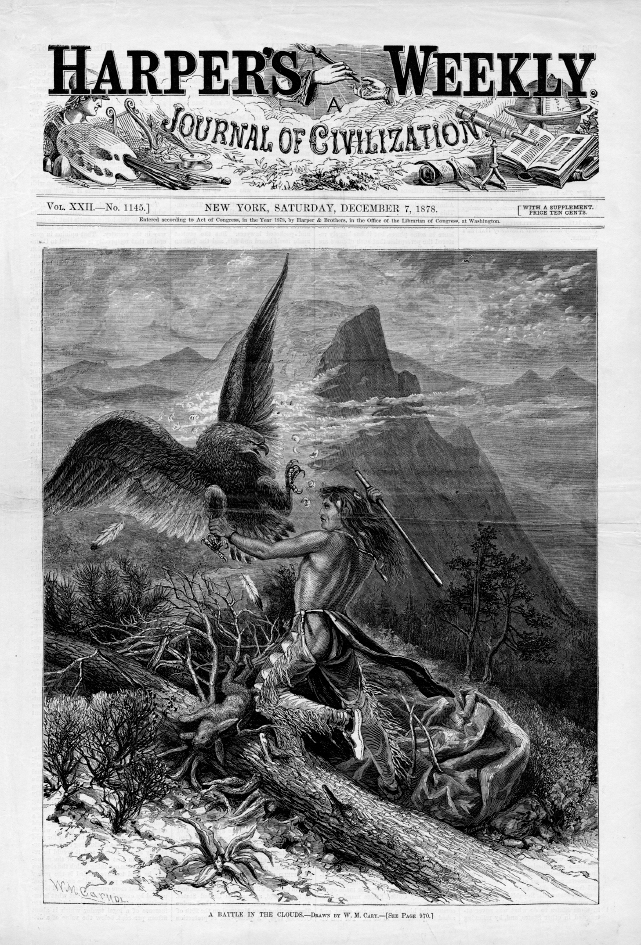

The cover of Harpers Weekly on December 7, 1878, featured an extraordinarily dramatic Indian illustration. The full-page engraving, A Battle in the Clouds, showed a resolute, bare-chested warrior battling an enraged eagle lured to a mountaintop using a rabbit as bait

This illustration was cover material in Harpers Weekly because it presentedin a visually exciting waya powerful Indian warrior in the midst of a violent quest, a battle between a proud but uncivilized American savage and a wild and dangerous predator. In other words, this illustration was published on the cover because it represented a remarkable encounter in the American wilderness, a mythic scene of untamed Western life that the editors hoped would capture the publics imagination and, if they were lucky, draw a few more readers to the weekly.

This striking scene was largely imaginary, however, its details most likely based on a thrilling but secondhand tale of Indian adventure in the American West. an illustration published more for its visual appeal than for its news value. The imaginary nature of this illustration was not a problem for Cary, the editors, or the papers readers. After all, this was a bold and wildly romantic scene, true in a symbolic, if not literal, sense. This illustration also carried a particular set of Indian meanings because it represented some of the qualities that made the Noble Savage actually noble and, for that matter, savage. Again, there were clues in the published explanation: Attacking the king of birds with his coup stick, instead of with the rifle or the bow, is probably an act of bravado, to display his prowess for the admiration of some dusky coquette of the forest. This warriors dangerous encounter with the eagle, then, was not about feathers at all, or at least not entirely. It was a feat of Indian derring-do meant to catch the eye of a certain dusky woman.

FIGURE 0.1. W. M. Carys 1878 cover illustration for Harpers Weekly was more imagination than reality, an idealized Noble Savage created for popular consumption.

This example of Native American male braveryromanticized in Carys imagination to attract white, middle- and upper-class class readers from across the United Statesreveals a number of important ideas surrounding the popular image of the American Indian in the last half of the nineteenth century. Carys valiant warrior was a nineteenth-century representation of a good Indian, a popular and aesthetically pleasing Noble Savage. This idealized figure gave Harpers and its readers a way to see and appreciateat a superficial levelthis aboriginal American man, an extraordinary warrior rising from savagery to become a heroic (and virile) American symbol. This book is a study of such Indian imagesromantic, violent, racist, peaceful, and otherwisein the nineteenth-century illustrated press. More specifically, this research offers a social and cultural history of Indian illustrations during the heyday of the illustrated press. This erathe pictorial press erawas marked by a proliferation of detailed, realistic woodblock engravings, pictures of newsworthy people and interesting events from across the nation and the world. These pictures formed the basis for a new product in American journalism, the illustrated press, picture-packed weekly newspapers that prospered in the last half of the nineteenth century. The time was ripe for pictorial journalism, historian Joshua Brown has noted. By the mid-1850s the transportation revolution, innovations in printing technology, and an expanded literary and pictorial market came together to provide almost all the conditions necessary for a commercially viable illustrated press. These papers were part of a visual revolution in nineteenth-century journalism that brought imagesincluding hundreds of news and feature pictures of Native Americansinto the lives and imaginations of ordinary American readers.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.