Also by Alan Taylor

The Divided Ground:

Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution

Writing Early American History

American Colonies

William Coopers Town:

Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic

Liberty Men and Great Proprietors:

The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 17601820

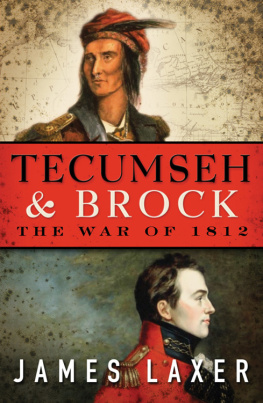

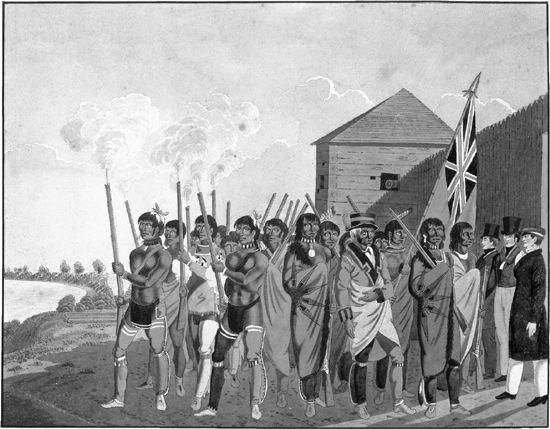

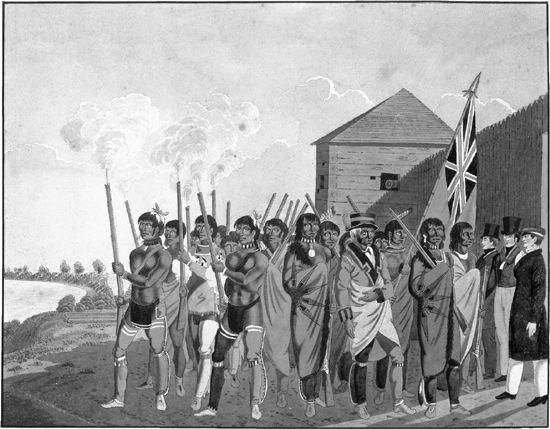

War Party at Fort Douglas, watercolor by Peter Rindisbacher, 1823. Indian allies of the British discharge their guns to salute the commander, Captain Andrew Bulger, who appears at the far right. This watercolor represents an incident during the War of 1812. (Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum, Canadiana Department, Sigmund Samuel Collections, 951.87.3.)

This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2010 by Alan Taylor

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Alan, [date]

The civil war of 1812 : American citizens, British subjects, Irish rebels, and Indian allies / Alan Taylor. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59459-4

1. United StatesHistoryWar of 1812Social aspects. 2. OntarioHistoryWar of 1812Social aspects. 3. Northern boundary of the United StatesHistory19th century. I. Title.

E354.T39 2010

973.52dc22 2010012783

v3.1

For the McIntyreVon Herffs,

Sheila and Michael,

William, Silas, and Lucy,

and Maggie the Magpie

Contents

INTRODUCTION

As much as the people of the two nations resemble each other in face, it is notoriously evident that there are some in America whose souls are perfectly British, and it is believed that there are some in Britain who are Americans at heart. It is not where a man was born, or who he looks like, but what he thinks, which ought at this day to constitute the difference between an American [citizen] and a British subject.

An American Farmer, 1813

I N THE FALL OF 1812 , Ned Myers, nineteen years old, marched across New York State with a party of fellow sailors bound for Lake Ontario, where the American navy was building warships for an invasion of British Canada. But Myers felt the enemy long before he reached the Canadian border. In northern New York, the sailors came to a village where the inhabitants bitterly opposed the war. On a trumped-up charge, the villagers arrested the officers in command of Myerss party but released them when the sailors threatened to burn the village. Moving on to Oswego Falls, the sailors got caught in a downpour, and sought refuge in a large barn. That night, as Myers recalled, they caught the owner coming about with a lantern to set fire to the barn, and we carried him down to a boat, and lashed him there until morning, letting the rain wash all the combustible matter out of him. In the War of 1812 Myers had to fight against Americans as well as Britons.

During the following summer on Lake Ontario, a British warship captured the schooner that Myers served on. As a prisoner, Myers dreaded the discovery of his secret: that he had been born a British subject in Quebec in 1793. Abandoned by his father, a German officer serving in the British army, Myers had grown up in Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, another British colony. At age eleven he ran away to New York City to become a sailor. Rejecting his birthright as a British subject, Myers chose to become an American citizen: America was, and ever has been, the country of my choice, and while yet a child I may say I decided for myself to sail under the American flag; and if my father had a right to

But the British insisted that every natural-born subject remained so for life. Before the war, Myers had repeatedly and narrowly dodged the Royal Navy press-gangs, which stopped and boarded American ships in search of any mariner who seemed British. And once the war began, British officers treated former subjects as traitors if they were captured while fighting in the American service. As a British prisoner, Myers feared for his life.

In September at Quebec, a press-gang boarded his prison ship to seize Myers and seven other prisoners. Myers insisted that five of them were Americans by birth, but a British naval officer pronounced us all Englishmen obliged to serve in the Royal Navy or face trial and hanging as traitors. All eight refused to serve on a warship, but consented to work on an unarmed transport vessel. They sailed for Bermuda, where naval officers again impressed them to serve on a warship, which threatened to swallow us all in the enormous maw of the British navy. Refusing again, the captives hazarded a court-martial. Unable to prove that the sailors were subjects, the British transferred them to a prison at Halifax, where Myers worried that the locals would remember and recognize him.

The War of 1812 pivoted on the contentious boundary between the kings subject and the republics citizen. In the republic, an immigrant chose citizenshipin stark contrast to a British subject, whose status remained defined by birth. That distinction derived from the American Revolution, when the rebelling colonists became republican citizens by rejecting their past as subjects. An immigrant reenacted that revolution by seeking citizenship and forsaking the status of a monarchs subject. But the British denied that the Americans could convert a subject into a citizen by naturalization. By seizing supposed subjects from merchant ships, the Royal Navy threatened to reduce American sailors and commerce to a quasi-colonial status, for every British impressment was an act of counterrevolution. By resisting impressment and declaring war, the Americans defended their revolution.

War raised the stakes in the conflict over subjects and citizens. By converting prisoners or hanging a few as deserters, the British bolstered their contention that any natural-born subject owed allegiance for life, no matter where he went or what nation pretended to naturalize him. Returning the favor, the republics officers sought to entice captive Britons to enter the American service, thereby reenacting the revolution on an individual scale. Because the line between citizen and subject was so contested, rival commanders promoted the desertion of enemy soldiers, the defection of prisoners, and the subversion of civilians in occupied regions. As much as on any battlefield, the British and the Americans waged the War of 1812 in the hearts and minds of Ned Myers and his fellow soldiers and sailors on both sides.

REVOLUTION

In the American Revolution the victorious Patriots forsook the mixed constitution of Great Britain, where a monarch and aristocrats dominated the common peoplethen the norm throughout the world. In a radical gamble, the Patriots created a republic premised on the sovereignty of the collective people, rather than of a monarch and his parliament. Meant to protect and promote the liberty, property, and social mobility of ordinary white men, the republic bred a suspicion of governments power as a tool for aristocrats to live as parasites on the labor of the people. But that republic for white men hastened the dispossession of Indians and prolonged the enslavement of African-Americans in the southern states. And the British despised the new republic as a dangerous folly, for they celebrated their mixed constitution as more stable, just, and powerful. Where Americans sought to disperse and reduce the power of government, the British sustained an empire with the coercive energy to regulate liberty, particularly that of their colonists and the sailors needed for the Royal Navy.