Contents

Page List

Guide

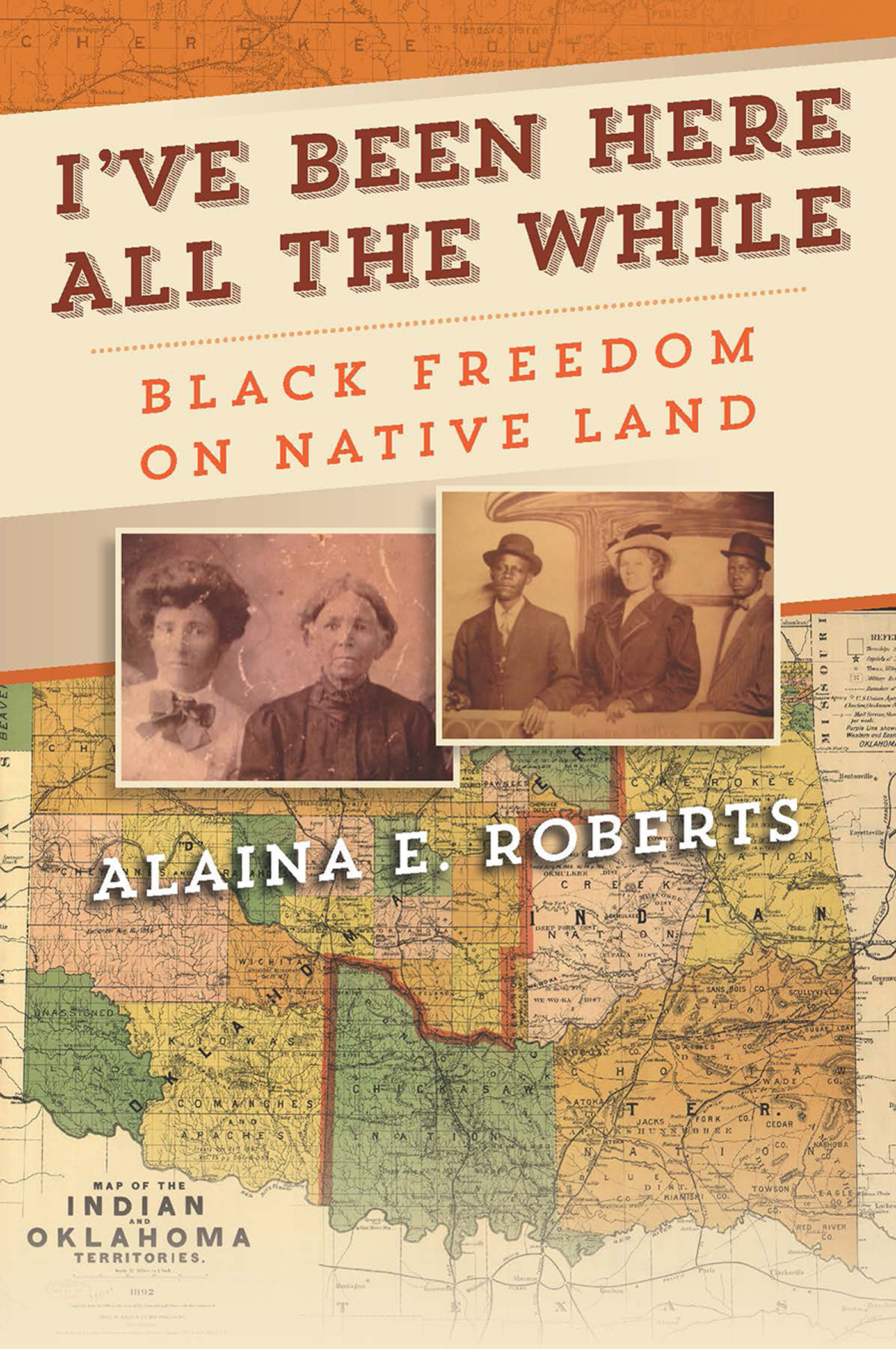

Ive Been Here All the While

AMERICA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Series editors

Brian DeLay, Steven Hahn, Amy Dru Stanley

America in the Nineteenth Century proposes a rigorous rethinking of this most formative period in U.S. history. Books in the series will be wide-ranging and eclectic, with an interest in politics at all levels, culture and capitalism, race and slavery, law, gender and the environment, and regional and transnational history. The series aims to expand the scope of nineteenth-century historiography by bringing classic questions into dialogue with innovative perspectives, approaches, and methodologies.

Ive Been Here All the While

BLACK FREEDOM ON NATIVE LAND

ALAINA E. ROBERTS

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2021 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

A Cataloging-in-Publication record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-5303-0

For all the dearly departed members of the Roberts family, but especially for Travis Roberts. You were the family historian long before I was born, and this book would not be what it is without your remembrances. Thank you for safeguarding this knowledge for us all and for being so generous with your time. I wish you were here to see our family story finally told in print

I feel so fortunate to have been born into a story so rich I can barely believe it at times. I know that I was gently led to this scholarship by my ancestors, and I hope that I have done justice to their stories and to the stories of the millions of African, African American, and mixed-race people who shared similar experiences

Contents

Introduction

W HEN MY GREAT-GREAT-UNCLE Eli Roberts described his familys arrival as enslaved people in Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma) from the Mississippi Chickasaw homelands in the mid-1800s, he detailed a world distinct from that which they had left. The fertile, green grasses of Mississippi metamorphosed into red and brown clay, and the southern pathways that had become crowded with white settlers clamoring for land were suddenly wide-open spaces occupied predominantly by Indians and Black people. In his childhood western home, he recounted to an interviewer with the Works Progress Administration in 1937: It was wild tribes of all kinds, animals, hogs, cowseverything was wild. We wore shirts and they were woven. We made moccasins out of buck skin. There werent any bridges. There werent any typewriters. We had stage routes, trails, and no newspapers. The country was all open Indian lands. Just one store and post office, plenty game and fish, and no homesteaders. We had lots of horse racing, but no medicine, and no settlements.

Soon, however, this western space began to resemble the southern homelands that its Native settlers had been forced by the U.S. government to leave behind. The Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole Nations (also known as the Five Tribes) had brought their slaves, their distaste for foreign American oversight, and their proven adaptability to Indian Territory. The wealthy citizens of these Indian nations rebuilt their plantations larger than before, increasing their cotton production, cultivated by an enslaved populace that grew to make up approximately 14 percent of Indian Territorys total population by 1860. As white Americans argued over Black humanity and the spread of slavery, the Five Tribes were swept into analogous disputes that sparked discord and challenged their notions of race and kinship. In the war that followed, both white and Indigenous slaveholding societies fractured. After their ideological and martial involvement in the Civil War, Indian nations, too, experienced a Reconstruction period. Like their white southern counterparts, they resisted emancipating and enfranchising their former slaves until the United States intervention compelled them to do so. But for Indian nations, this federal intervention represented a combination of the American obsession with the spread of slavery in the West and a fixation on the seizure of western Indian land.

It is this connection between North American slavery, Black freedom, and settler colonialism that constitutes the nucleus of this book. What do I mean by settler colonialism? Scholars from a number of disciplines have traditionally defined settler colonialism as the exploitation of a region or countrys resources and labor, plus the forcible resettlement of Indigenous peoples and their replacement by settlers who then move onto their lands and rewrite history in an effort to erase the longevity of their presence, and often their very existence. Because throughout the Americas, Africa, Australia, and the Pacific Islands the settlers who have put these practices into motion have, for the most part, been white, settler colonialism also involves an element of racial ideology, specifically the idea that white dominion in political, social, and economic systems and control over land is natural and logical.

In Indian Territory, I identify settler colonialism as a process that could be wielded by whoever sought to claim land; it involved not only a change in land occupation but also a transformation in thinking about and rhetorical justification of what it meant to reside in a place formerly occupied by someone else. This means that, in my definition, anyone could act as a settler, despite previous status as, say, a slave or a dispossessed Indian, as long as they used this processcomposed of rhetoric, American governmental structures, and individual actionwhich may have aided in their efforts to acquire land or protection but which ultimately served the goals of spatial occupation and white supremacy: the dual nature of settler colonialism. Power did not emanate from only one person or governmental agency. Rather, these settlers appealed to tribal agents, the secretary of the interior, various governmental commissions, the president of the United States, and so on. Together, these sources of power made up the settler colonial state.

The settlers I follow are members of the Five Tribes (especially Chickasaws and Cherokees), Indian freedpeople (Black people once owned by members of the Five Tribes), and Black and white Americans. These overlapping waves of settlers employed particular iterations of settler colonialism to justify their claims to the land in Indian Territory, and hence to privileges of citizenship or communal belonging. The terms I use for people of African descent throughout this book are a mixture of historical creation and historians interventions. Freed African Americans were often referred to as freedmen in their own time (for instance, the governmental agency charged with helping them to acclimate to freedom was called the Freedmens Bureau). In the same historical moment, the U.S. government referred to Black people owned by Native Americans, and their descendants, as Chickasaw freedmen, Cherokee freedmen, and so on, to differentiate their histories of enslavement from those of Black people in the United States and to categorize them for the purpose of resource distribution. I use Indian freedpeople as a gender-neutral catchall to refer to formerly enslaved women and men from all of the Five Tribes. Though today the descendants of Indian freedpeople identify, for the most part, as African American, here I largely refer only to those people of African descent who lived in the United States as African American to call attention to their nationalities. Indian freedpeople were part of the Indian nations they were connected to, and, as such, I believe that calling them African American is anachronistic.