Black Indian

Slave Narratives

Published by John F. Blair, Publisher

Copyright 2004 by Patrick Minges

All rights reserved under International and

Pan American Copyright Conventions

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

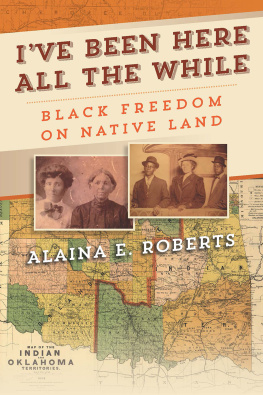

Cover Image:

Morris Sheppard, a Freedman.

Foreman Call. Photo number 10753

Courtesy of Research Division of the Oklahoma Historical Society

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Black Indian slave narratives / edited by Patrick Minges.

p. cm. (Real voices, real history series)

ISBN 0-89587-298-6 (alk. paper)

1. SlavesUnited StatesInterviews. 2. FreedmenUnited StatesInterviews. 3. African AmericansInterviews. 4. Indians of North AmericaMixed descentInterviews. 5. African AmericansRelations with Indians. 6. SlavesUnited StatesSocial conditions. 7. Indians of North AmericaMixed descentSocial conditions. I. Minges, Patrick N. (Patrick Neal), 1954- II. Series.

E444.B615 2004

306.362092273dc22 2004004887

Design by Debra Long Hampton

To Mattie Louis Crisp Minges, my mother

Contents

This book began some fifteen years ago. While I was working on my dissertation on slavery in the Cherokee Nation, I went to the W.P.A. ex-slave narratives as a major resource for research. I was led down this path by two persons whose scholarship has profoundly influenced my ownTheda Perdue and Daniel Littlefield. In their pioneering efforts, they used the ex-slave narratives to explore and present the histories of the Five Nations of the American Southeast from a totally different perspectivethat of the African American members of these nations. Professor Perdues work, Nations Remembered: An Oral History of the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles in Oklahoma, 1865-1907, which extensively utilized the Indian Pioneer Papers, was influential in the way that it opened up this other collection of W.P.A. first-person narratives as a historical resource.

So I decided to start looking at the ex-slave narratives for stories about the Indian Territory from the perspectives of those doubly displacedpersons of African American descent within what had become known as the Five Civilized Tribes. Critical to this effort was Betty Bolden, senior library associate for Reader Services of Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, who worked through interlibrary loan to bring countless rolls of microfilm of these narratives to me. Her diligence and patience played an important role in my being able to bring these narratives to you. I also want to thank Herbert, the microfilm reader on the first floor of Burke Library, with whom I developed an intimate and enduring relationship. In all seriousness, the administration and staff at the library were always supportive of this often idiosyncratic quest. In addition, numerous librarians and archivists at the Newberry Library, the New York Public Library, Butler Library, the Oklahoma Historical Society, McFarlin Library, the John Vaughan Library, Gilcrease Institute, and the Western History Collections all provided support and guidance.

A lot of people have shown an interest in these narratives, which helped push me into seeking their publication in this form. Among the first were Tiya Miles and Celia Naylor-Ojurongbe, two colleagues whose dissertations were similar to mine and whose consideration of the value of the narratives prompted me to further research and development. A couple of other colleagues, Eleanor Wyatt and Angela Y. Walton-Raji, have worked on similar projects over the years. Their support and friendship have proven invaluable.

However, my most important contributors have been the folks at John F. Blair, Publisher. Their vision in recognizing the importance of this project and their patience with me in helping bring it to fruition have been immeasurable. I would like to offer a special word of appreciation to Carolyn Sakowski, who was my mentor in this process and whose assistance in editing the narratives was substantial. Thanks also go to Ed Southern, Anne Waters, Kim Byerly, Stephen Kirk, Sue Clark, and Debbie Hampton. Something such as this is difficult to pull together except by a collective effort.

I thank my mother for the many years of tireless support and unfailing love she has given me. Everything that I have is a direct result of her devotion to me. If books are the products of how our lives have shaped us, then this book is a reflection of my mothers love. My brothers keen intellect and my fathers profound wisdom have also had a dramatic influence on shaping my professional life.

Some things are so wonderful that God gives us two of them; I have been blessed with another family. I would like to thank Carl, Marion, and Rip for giving me unconditional love and encouragement.

I also want to acknowledge my four-legged co-conspiratorsKarma, Geronimo, Satori, Ashoka, Deva, and Selufor helping me keep my perspective on what is really important.

Lastly, none of this would have been possible without the tremendous patience and love of my wife, Penny, who has not only tolerated my endless hours staring at computer screens but also the countless photocopies of narratives filling every available binder. She helped me organize all the various components of this project and provided me counsel and guidance. She is a very special blessing for me.

De nigger stealers done stole me and my mammy outn de Choctaw Nation, up in de Indian Territory, when I was bout three years old. Brudder Knex, Sis Hannah, and my mammy, and her two step-chillun was down on de river washin. De nigger stealers drive up in a big carriage, and Mammy jus thought nothin, cause the ford was near dere, and people goin on de road stopped to water de horses and res awhile in de shade. By and by, a man coaxes de two bigges chillun to de carriage, and give dem some kind-a candy. Other chillun sees dis and goes, too. Two other men was walkin round smokin and gettin closer to Mammy all de time. When he kin, de man in de carriage get de two big step-chillun in with him, and me and sis clumb in, too, to see how come. Den de man haller, Git de

Spence Johnson

On that day, the lives of Spence Johnson and everyone around him took a sudden and dramatic turn. One minute, he and his family were by the river washing clothes; the next, they had been seized by nigger stealers and sold down the river to Louisiana. Whereas once they were among the finest families of the Choctaw Nation, they now found themselves on the auction block, being sold to the highest bidder as commodities on the slave market. Speaking only their native tongue, they were suddenly cast adrift in a world of words and symbols they little understood, facing a plight unprecedented in their experience. As they came to find out, the line between blacks and Indians in the nineteenth century was hardly as wide as many had thought. It seems that slaves came in many colors, and that the peculiar institution was no respecter of persons.

Equally, the narrative of Spence Johnson can help us reshape our world view and bring us to look at the institution of slavery in a different light. We have notions of what a slave was and what slavery was like. Our recorded histories have detailed the capture of indigenous persons from the west of Africa, their horrific middle passage to America, and their eventual lives under the brutal institution of chattel slavery. The very notion of the slave narratives conjures up images of aged blacks only a short time removed from their plantation life depicting, sometimes quite fondly, the institution that so shaped their lives and the lives of their ancestors. It is an image of stark contrasts of black and white.

Next page