PREFACE

It is one thing to write as a poet and another to write as a historian: the poet can recount or sing about things not as they were, but as they should have been, and the historian must write about them not as they should have been, but as they were, without adding or subtracting anything from the truth.

Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

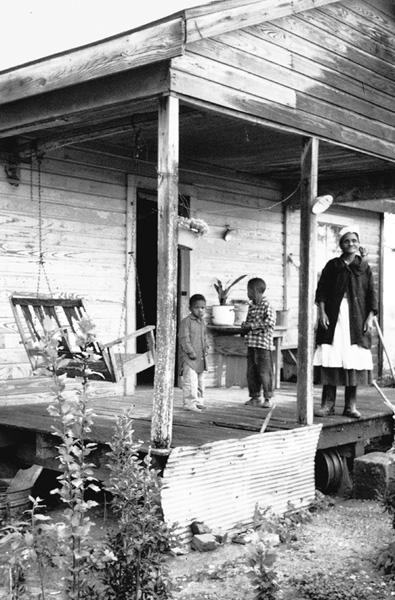

Dispossession focuses on the third quarter of the twentieth century. Usually referred to as the civil rights era, this was a moment of extraordinary transformation in the rural United States. Science and technology applied to agriculture increased yields, made hand labor obsolete, and, combined with federal programs, drove 3.1 million farmers from the land. In the quarter century after 1950, over a half million African American farms went under, leaving only 45,000. In the 1960s alone, the black farm count in ten southern states (minus Florida, Texas, and Kentucky) fell from 132,000 to 16,000, an 88 percent decline. Whites also left southern farms during this decade, though the decrease was not as dramatic: 61,000 farms remained of the 145,000 a decade earlier, a 58 percent decline.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) dismissed farm failures as the natural consequence of farmers adoption of machines and chemicals, but in fact, the USDA shamelessly promoted capital-intensive operations and used every tool at its disposal to subsidize wealthy farmers and to encourage their devotion to science and technology. New was better; old was not meant to survive. By the 1950s, the intrusive tentacles of agrigovernment uncoiled from Washington through state and county offices and, paired with agribusiness, reconfigured the national farm structure. At the same time, the USDA erected high hurdles, often barriers, that discouraged or prevented minorities and women from securing acreage allotments, loans, and information. Paradoxically, the earlier increase in the number of black farms to a high of 925,000 by 1920 occurred during some of the nations worst years of violence and discrimination since the Civil War, and the decrease intensified when government programs, civil rights laws, and science and technology promised prosperity and fair treatment. During this period, despite the profound implications of demographic chaos, the press seldom mentioned dispossession.

African American farmers stubbornly refused to go quietly from their farms and eloquently articulated and bravely resisted the discrimination that threatened them. They ran for county committee seats, confronted county executives, applied for loans, and brought suits to challenge discrimination. They were often unable to obtain credit, the sine qua non for modern agriculture, even for spring planting, much less for buying tractors, picking machines, and chemicals, nor were they favored by USDA personnel or policies. From its inception in 1862, the USDA was run by white men and, with the exception of the Negro Extension Service, excluded African Americans from decision-making positions.

The civil rights and equal opportunity laws of the mid-1960s prompted USDA bureaucrats to embrace equal rights rhetorically even as they intensified discrimination. This passive nullification, voicing agreement with equal rights while continuing or intensifying discrimination, did not rely on antebellum intellectual arguments or confrontations but instead thrived silently in the offices of biased employees. Phone calls and conversations at segregated meetings and conventions left no racist fingerprints, but the accretion of prejudice festered and ultimately grew into a plan to eliminate minority, women, and small farmers by preventing their sharing equally in federal programs. Despite overwhelming evidence of discrimination, incompetence, and falsehoods in many offices, the USDA never cut off funds to those offices, and apparently no white person was fired and few were even relocated or reprimanded.

An impressive number of organizations assisted black farmers in coping with bias in the USDAs Washington headquarters and in states and counties throughout the South, and young civil rights workers, African American farmers, and black extension agents made heroic contributions. This book focuses on the years prior to the Pigford v. Glickman decision in 1999, a class-action suit that won compensation for discrimination after 1981. Pigford exposed interminable USDA bias and established precedent for similar suits by Native Americans, women, and Hispanics. During the height of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, however, there was no check on USDA discrimination. Indeed, after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, southern USDA offices twisted programs to punish black farmers who were active in civil rights, and administrators in Washington acquiesced.

This book examines three USDA agencies: the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service, the Federal Extension Service, and the Farmers Home Administration. These powerful pseudo-democratic agencies became repositories of prejudice and discriminatory practices as they hired office staffs, selected extension and home-demonstration agents, controlled information, adjusted acreage allotments, disbursed loans, adjudicated disputes, and, in many cases, looked after their own families and friends. The focus of this book seldom widens from farm issues, although the turbulent decade of the 1960s offered tempting diversions. The farmers and bureaucrats who appear in the pages that follow have seldom emerged as historical players, but they are an important part of the history of both the civil rights era and American agriculture.