ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As with any book about a community, it took many people to make it successful. We recognize that this book on the African Americans of Jefferson County is far from complete. This is simply a pictorial history of the photographs available to us. We attempted to include photographs from the various communities in the county. Where we could not, we apologize.

All photographs are from the archives of the Jefferson County Black History and Preservation Society. We want to give special thanks to the Wainwright Baptist Church, Mount Zion United Methodist Church, and Star Lodge No. 1 F&AM for the use of their facilities as scanning sites for the project. We received and scanned numerous photographs from many people and sources. We are very grateful to the following people and sources that shared their photographs with us: Library of Congress, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, collection of Jefferson County Black History Preservation Society, the Ohio Historical Society, Jefferson County Museum, Page-Jackson Alumni Association, Bill Theriault, Fannie Hazelton, Linda Downing, Guinevere Roper, Ira J. Pendleton, Velma Twyman, Larry Togans, Claude Stanton, Ora Jean Reeves, Brenda Branson Johnson, Fonda Barron, James L. Taylor, Richard Clark, Gordy Clark, Janet Jeffries, James A. Tolbert, George Rutherford, Madeline McIver, James Surkamp, Sylvia Rideoutt Bishop, Cheryl Roberts, Ruth McDaniel, Rachel Johnson Canady, Charles Ferguson, Larry Good, Edith Clay, Jean Lee Roberts, Johnny Bailey, and the Dorothy Young Taylor Collection. In addition, the Historical Digest of Jefferson County, West Virginias African American Congregation 18591994 , by Evelyn M. E. Taylor, Thomas J. Scott, and Vivian Jackson Stanton was a very helpful resource.

We want to extend a special thanks to Dolly Nasby, whose assistance in every aspect of this project was invaluable, and without her help this book would not exist. We also extend our profound thanks to Linda Murr for proofing this publication.

We also wish to thank those of you who purchased this book. We hope you enjoy this pictorial history of the African American life in Jefferson County.

We dedicate this work to our parents and teachers for their vision and encouragement during times of segregation and for their unconditional love and their unwavering support.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

JOHN BROWNS RAID AND CIVIL RIGHTS

John Brown and his army of 21 men attacked the Federal Arsenal in Harpers Ferry in 1859. Many believe this event marked the beginning of the Civil War. Brown was eventually captured, tried, and found guilty in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia), of treason and then executed by hanging. Brown and his followers were despised by some; by others, Brown and his followers were considered martyrs. In 1906, members of the Niagara Movement (forerunner to the NAACP) held its first meeting on American soil at Storer College to pay tribute to John Brown and his followers.

World War I veterans requested an American Legion charter and then named their unit Green-Copeland Post No. 63. Members of Jefferson County Black Elks Lodge expressed their admiration by chartering the unit John Brown Elks Lodge. In 1932, NAACP members attending their national convention in Washington made a pilgrimage to Storer College to erect a tablet in memory of John Brown. It was rejected by college officials. However, in 2006, another pilgrimage was made to Storer College by NAACP national convention attendees, and the tablet was finally placed on the campus. Jefferson County civil rights history is extremely unique and has had a major national impact.

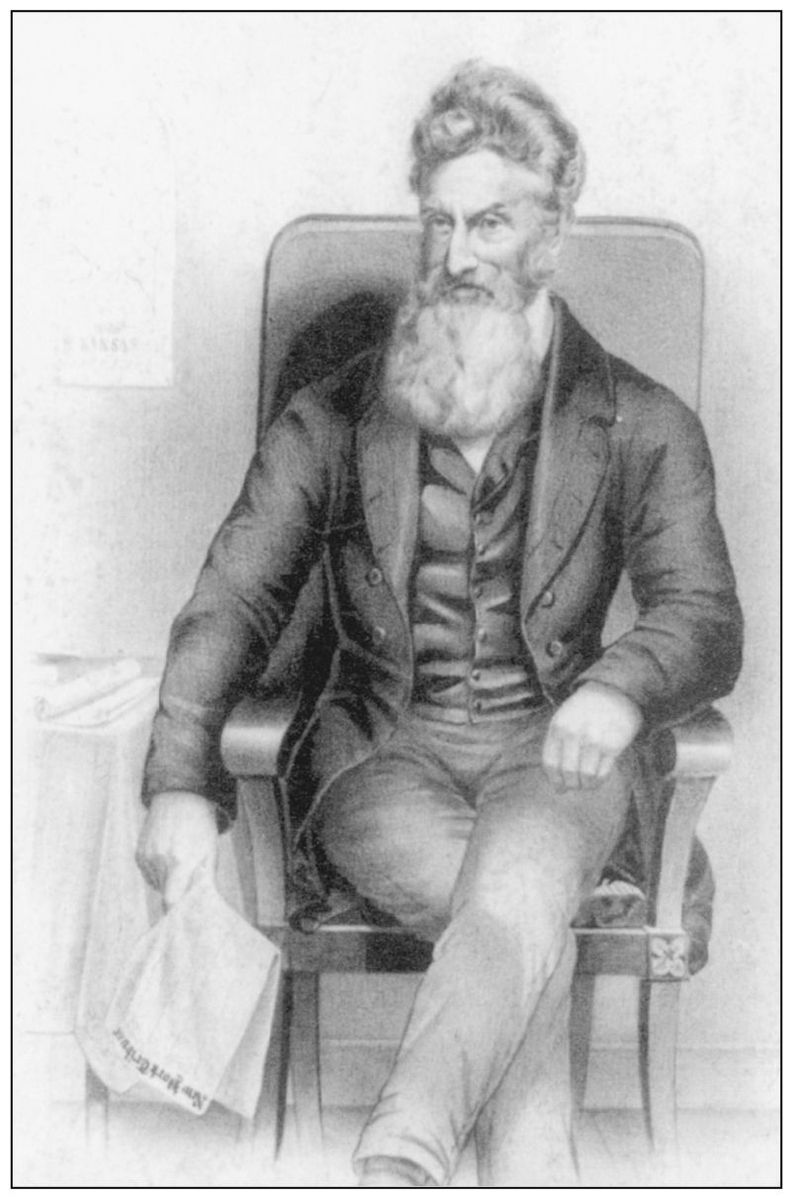

John Brown, an abolitionist, led the ill-fated 1859 raid on the Harpers Ferry Federal Arsenal, an event that would serve as a catalyst for the Civil War. He led 21 loyal followers and holed up on the Kennedy Farm in Maryland to plan their attack. The raid was very violentof the 22 raiders (including John Brown), 11 were killed, 7 were tried and hanged, and 4 escaped. Five were black.

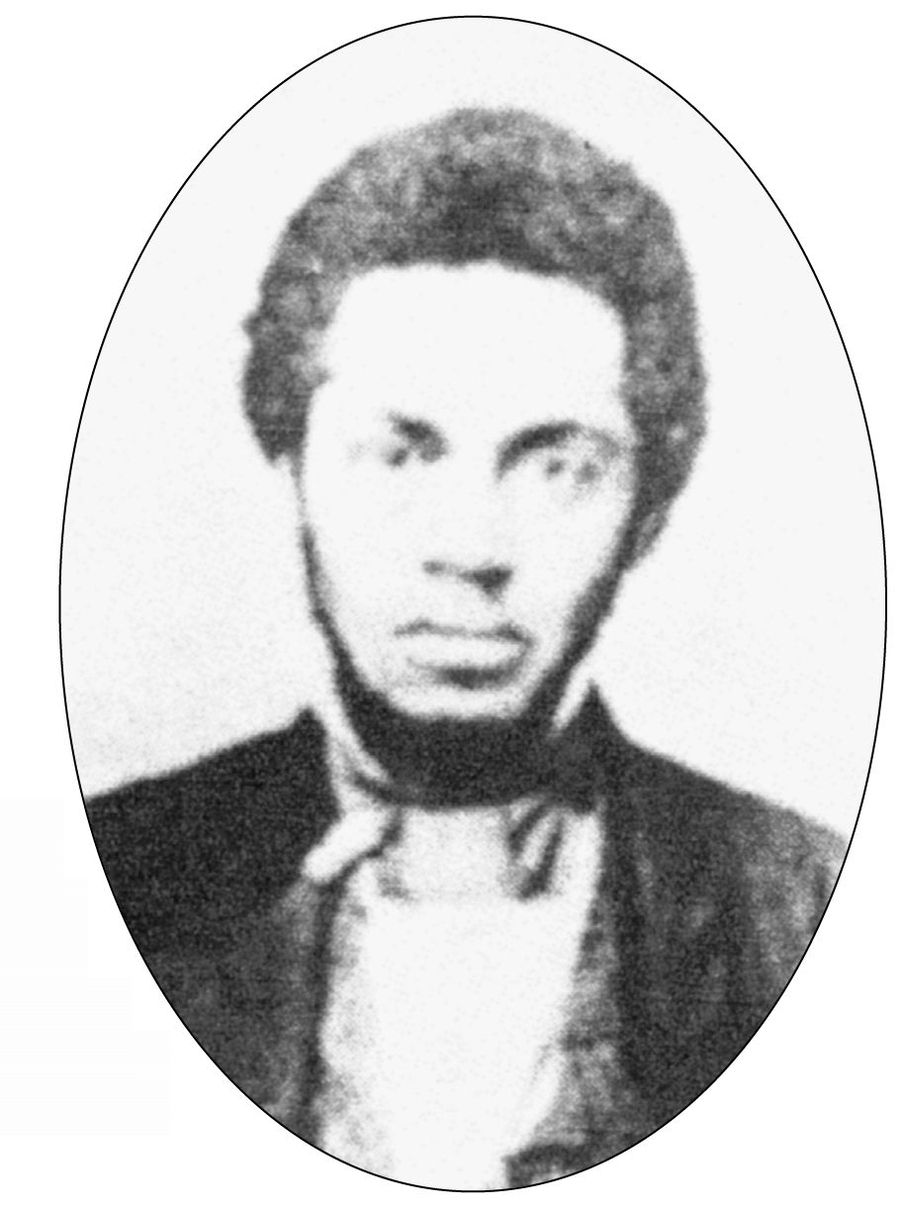

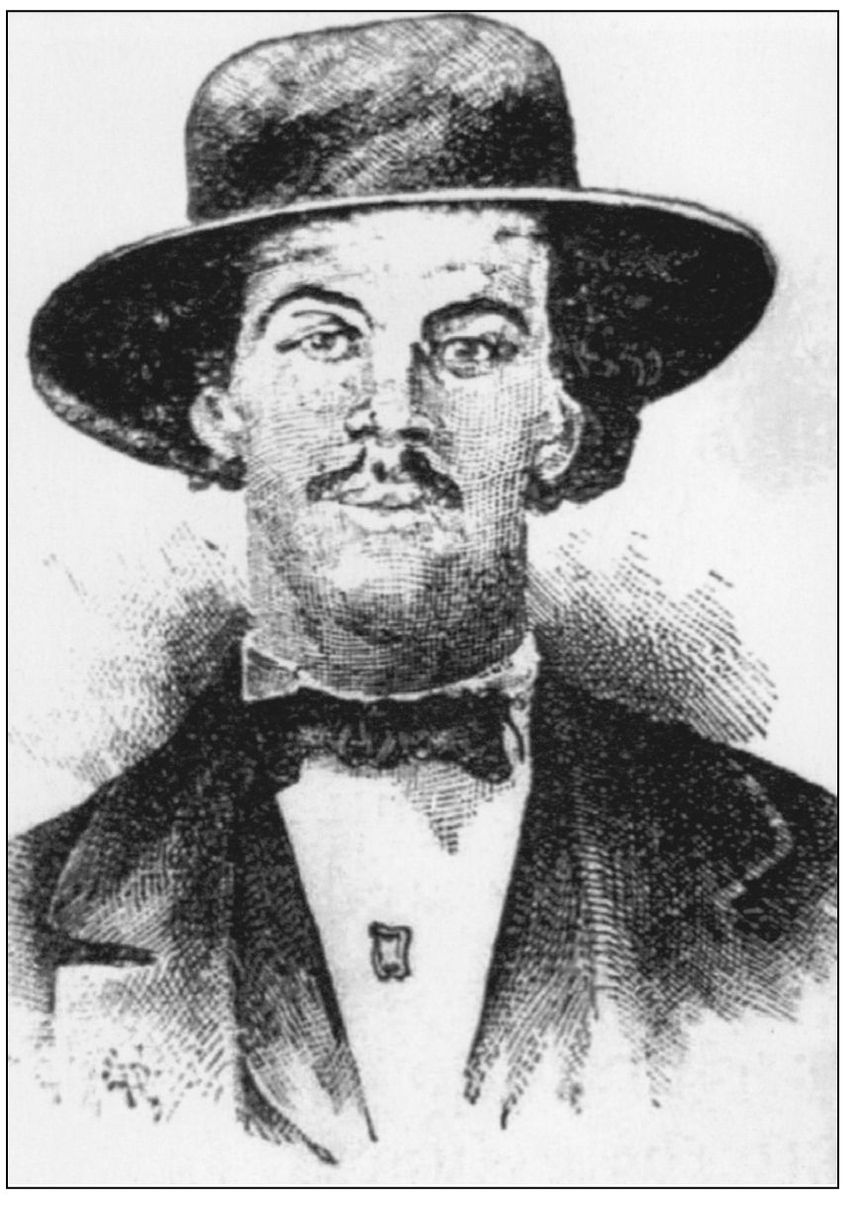

Osborn Perry Anderson was 30 years old at the time of John Browns raid. He first met John Brown in 1858 in Canada. He and Albert Hazlett (a white raider) held the arsenal while Brown gathered with his men in the engine house. He and Hazlett escaped. In 1864, Anderson enlisted in the army, where he became a noncommissioned officer. He died of consumption in Washington on December 13, 1872.

Lewis Leary was born to a slave mother and an Irish father who freed his mother and all the children she bore him. He grew up in Ohio, where he attended Oberlin College for a time. His wife, Mary Sampson, was the grandmother of poet Langston Hughes. During the raid, Leary was shot and died six hours later.

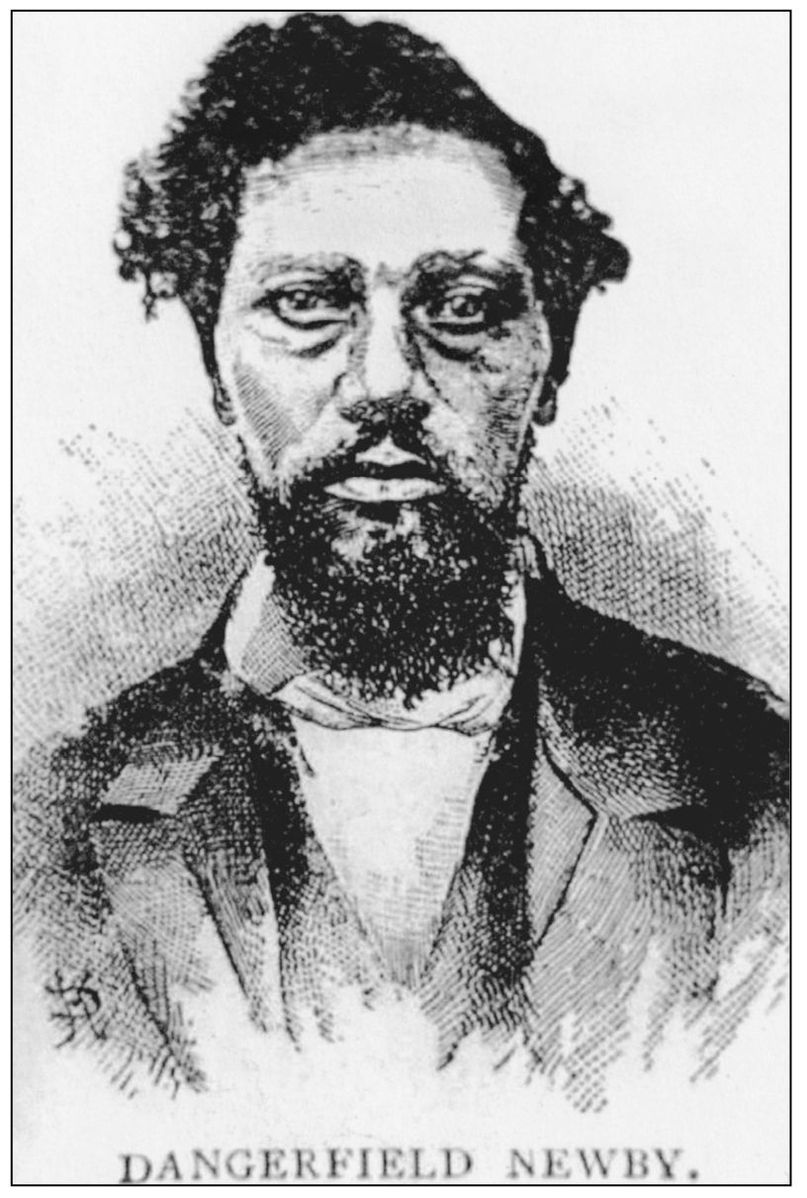

Dangerfield Newby was the first of 11 children who had a white father and a slave mother. Newby was shot by a person who was in a house on the opposite side of the street in Harpers Ferry. He was killed at the arsenal gate. His body was rooted by local hogs. He joined Browns army to free his wife and children, who were slaves near Warrenton, Virginia.

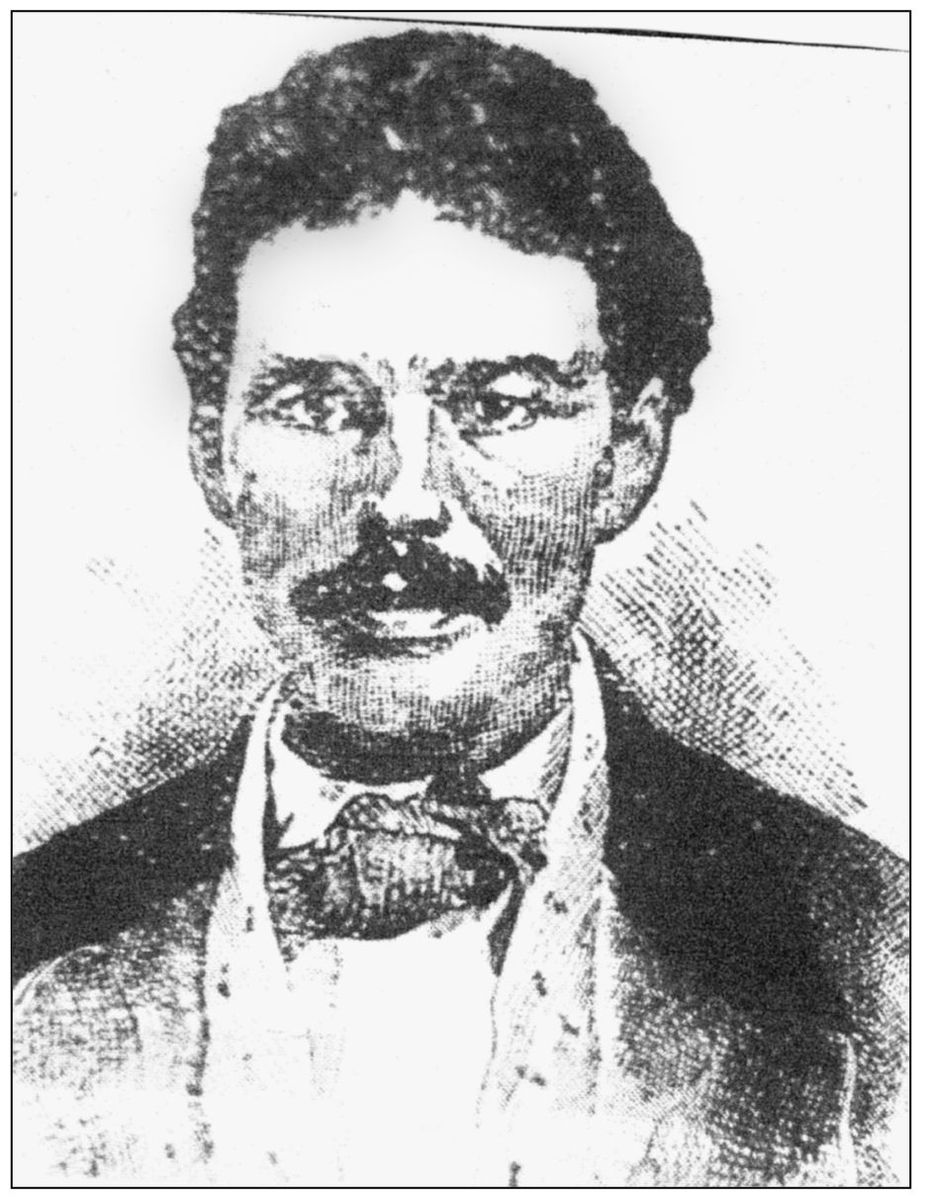

John A. Copeland was born in North Carolina, the son of Delilah Evans Copeland and John Copeland Sr., free blacks who settled in Oberlin, Ohio, where John Jr. studied at Oberlin College. He and Lewis Leary, related by marriage, arrived at the Kennedy Farm on the eve of the raid. He was captured, tried, convicted, and hanged in Charles Town. Medical students moved his corpse to the Medical College in Winchester, Virginia.

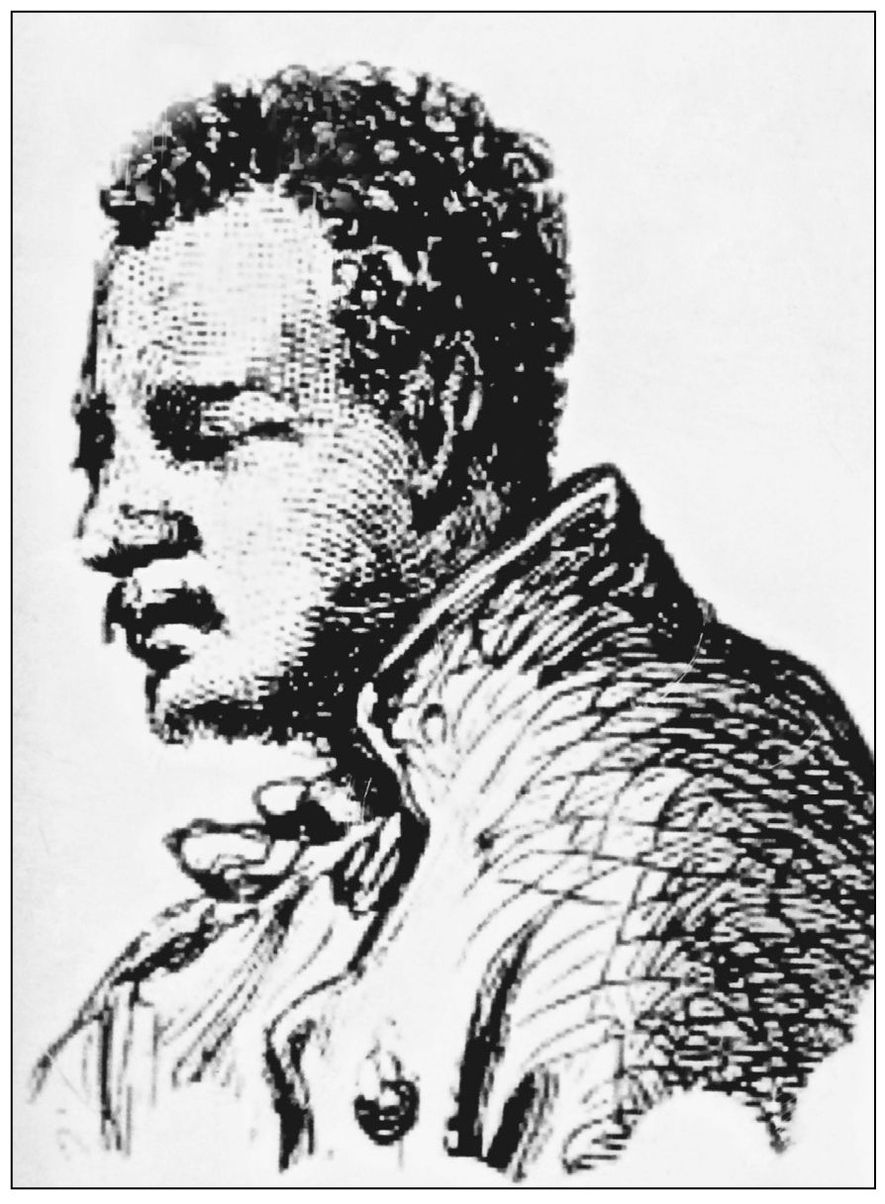

Shields Green, an escaped slave from South Carolina, was a protg of Frederick Douglass. He escaped to the North after his wife died. He changed his name from Esau Brown to Shields Green in order to escape detection. Green was one of five African Americansthe first recruitedto participate in John Browns raid in Harpers Ferry. He was captured, tried in Charles Town, and executed on December 16, 1859.