About the Author

Robert F. Jefferson, Jr. is an associate professor of history at the University of New Mexico. Dr. Jefferson holds a PhD in American history from the University of Michigan. Originally from South Carolina, he currently resides in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Appendix

CHAPTER 1

The National Convention of Colored Men

Around the same time, the National Convention of Colored Men assembled in Syracuse, New York. Nearly a hundred delegates packed the Wesleyan Methodist Church during a four-day period. There they heard speeches given by a wide array of noted social, political, civic, religious, and fraternal organization leaders, including John M. Langston, Henry Highland Garnet, Frederick Douglass, and Peter Clark. During the meeting, Garnet, a longtime advocate for black emigration prior to the war, reversed his stance and clamored for greater public recognition of African Americans in American society, based on the brave deeds of the colored soldiers and the effect their brave conduct had produced upon the public mind. Echoing Garnets remarks, John Rock of Boston pointed out to rousing applause that all we ask is equal opportunities and equal rights. This is what our brave men are fighting for. They have not gone to the battlefield for the sake of killing and being killed, but they are fighting for liberty and equality. We ask the same for the black man that is asked for the white man; nothing more, and nothing less.

Before the Syracuse meeting came to a close, delegates resolved to petition Congress, demanding black suffrage. They asked that the Congress use every honorable endeavor to have the rights of the countrys colored patriots respected, without regard to their complexion. [...] We believe that the generosity and sense of honor inherent in the great heart of this nation will ultimately concede us our just claims, accord us our rights, and grant us full measure of citizenship, under the broad shield of the Constitution, they concluded.

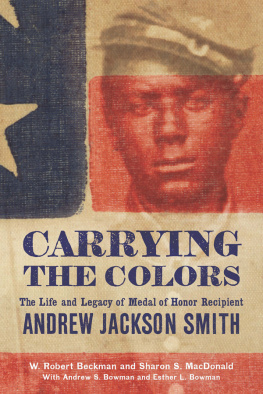

Delegates of the National Convention of Colored Men felt obliged to treat the exploits of MOH aspirants on the battlefield as markers in progress.

Christian Fleetwood and the Plight of Black Civil War Soldiers

Disillusioned with the army, Christian Fleetwood harshly criticized its treatment of black troops, and wrote an angry letter from the front:

Upon all our record there is not a single blot, and yet no member of this regiment is considered deserving of a commission, or if so, cannot receive one. I trust you will understand that I speak not of and for myself individually, or that the lack of the pay or honor of a commission induces me to quit the service. Not so by any means, but I see no good that will result to our people by continuing to serve; on the contrary, it seems to me that our continuing to act in a subordinate capacity, with no hope of advancement or promotion, is an absolute injury to our cause. It is a tacit but telling acknowledgment on our part that we are not fit for promotion, and that we are satisfied to remain in a state of marked and acknowledged subservience.

CHAPTER 4

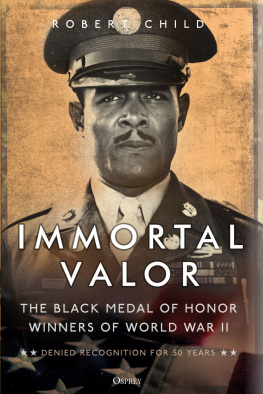

African-American Leaders and President Wilsons Unkept Promises

Among those reasonably impressed with Woodrow Wilson was W. E. B. Du Bois. The forty-four-year-old intellectual, propagandist, and founder of the Pan-African Congress had been the director of publicity and research in the fledgling National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for only a few years before presidential politics intervened. As the editor of the NAACPs house organ, The Crisis, Du Bois was initially inclined to support the Socialist Partys presidential nominee, Eugene Debs, but he later came to believe that African-American fortunes rested with the reform governor of New Jersey. Of Woodrow Wilson, he wrote in The Crisis, His personality gives us hope. He will not advance the cause of oligarchy in the South, he will not seek further means of Jim Crow insult, he will not dismiss black men wholesale from office, and he will remember that the Negro in the United States has a right to be heard and considered.

Du Bois was not the only leader who pinned his hopes on the Democratic Partys nominee for president that year. Wilsons promises of a New Freedom received a favorable response from Bishop Alexander Walters of the influential African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. Walters may have had even more reason to entertain raised expectations. During the presidential campaign, he received a letter from the aspiring candidate in which Wilson stated, The colored people of the United States have made extraordinary progress towards self-support and usefulness, and ought to be encouraged in every possible and proper way. My sympathy with them is of long standing, and I want to assure them through you that should I become President of the United States, they may count on me for absolute fair dealing and everything by which I could assist in advancing the interests of their race in the United States.

But to his dismay, the nation learned that Wilsons New Freedom did not include African Americans. Shortly after taking office, Wilsons first administration codified Jim Crow segregation in the nations capital by signing an executive order requiring photo identification for civil service applicants, and separating federal employees in the Treasury Department and the Post Office, as well as on public conveyances and in eating and restroom facilities. Whats more, in 1915, they were personally appalled when the first Democratic president since Grover Cleveland personally approved Hollywood producer D. W. Griffiths racist motion picture, The Birth of a Nation, based on Thomas Dixon Jr.s novel The Clansman. Griffiths cinematic representation of Reconstruction celebrated the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and demonized black men and women in the South. After a personal screening of the film in the White House, Wilson gushed, It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.

African-American Organizations and the Politics of Uplift

Sentiments of racial pride and black consciousness gave rise to a growing number of churches and clubs in cities stretching from Boston to Atlanta to Seattle. Between 1906 and 1911, a number of black fraternities and sororities were formed, including Cornell Universitys Alpha Phi Alpha, Indiana Universitys Kappa Alpha Psi, and Howard Universitys Omega Psi Phi, Alpha Kappa Alpha, and Delta Sigma Theta. And throughout the country, a growing number of black newspapers emerged to publicize the needs and concerns of ever-expanding black communities in New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, Norfolk, Savannah, and Los Angeles.

Black insistence on political rights and protections intersected with their sense of self, their demands for citizenship, and the need for a better class of leadership. As historian Kevin K. Gaines reminds us, a new generation of African Americans came of age at the turn of the twentieth century, and they advocated racial uplift as a means of refuting white claims of racial supremacy and black inferiority. According to Gaines, Believing that the improvement of African Americans material and moral condition through self-help would diminish white racism, educated African Americans sought to rehabilitate the races image by embodying respectability, enacted through an ethos of service to the masses.

Uninvited Neighbors: Hostilities between the United States and Mexico

A series of events occurred during the summer of 1917 that caused feelings of consternation among segments of the black community. Between 1914 and 1917, hostilities between the United States and Mexico had simmered to a boiling point as US Marines marched into Vera Cruz in response to a Mexican attack on American sailors in the area. Less than two years later, American troops marched to Mexico when Francisco Pancho Villa carried out raids on American civilians and soldiers who resided along its border. Vying to overthrow Mexicos provisional president, Villa hoped to lure the United States into a military skirmish. In response, Woodrow Wilson ordered fifteen thousand army troops to conduct a Punitive Expedition against the Villistas. Among the units that reported to duty was the famed 10th Cavalry, with West Point graduate Maj. Charles Young. Led by Brig. Gen. John J. Pershing, troops spent nearly a year in pursuit of Villa, to no avail. Foiled in their attempt to capture the Mexican revolutionary, and becoming increasingly drawn into a possible war with Germany, Pershings troops were withdrawn from the Mexican border.