October 1859

W illiam Harvey Carneys first breath of free air came in the form of a sneeze.

He had been lying in the warm dark, beneath a cloth in the back of the wagon, clutching his small sack of possessions to his chest. His eyes were open vigilance was the watchword on this journey but he had allowed himself to be lulled by the rocking rhythm of the wagon, humming the words to his favourite hymn silently in his head in time with the sway.

Suddenly the swaying stopped. William clutched his pack tighter. His heartbeat quickened. What was it? A checkpoint? A barricade? An armed band of fugitive-slave seekers? So far, he had been very lucky in his journey north, but every moment carried a heavy risk. He lay as still as he could, hoping his heartbeat wouldnt give him away. It was pounding so hard, he thought it might well be shaking the whole wagon.

He heard shuffling footsteps in the dirt. Then a deep, stretching sigh. The cloth covering him was whipped back, releasing a cloud of road dust upon him.

William sneezed.

God bless you, came a voice.

William squinted up into the bright morning sunshine. He already knew it was past dawn, as he had felt the sun warming the cloth for the last hour or so, but it was clearly shaping up to be a beautiful, shining day. He blinked until the face of the old-timer who owned the wagon came into focus.

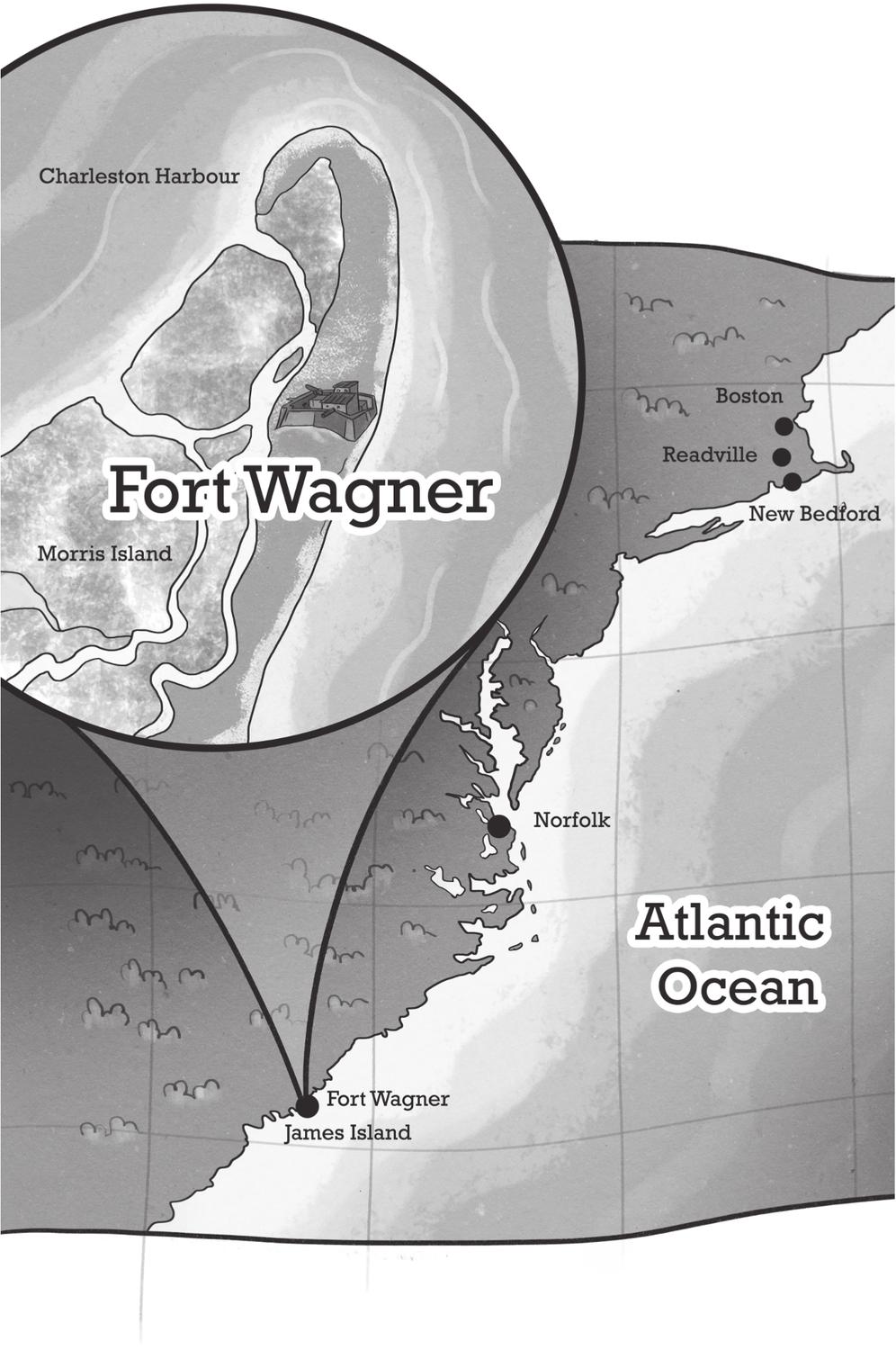

End of the line, the old-timer said. New Bedford, Massachusetts.

What? William said. New Bedford. Could it be? The words he had been dreaming about for years now had finally been uttered.

Hop on out. You need to ride up front now.

Up front? William echoed, as he scooted himself out of the wagon. His feet hit the dirt road steady.

The old-timer chuckled. I know youre not slow, he said. I seen that book youre carrying.

William clutched his pack tighter by impulse. The book was a notebook, into which hed copied his favourite Bible verses. His prized possession. He had secretly gone to school back in Norfolk, Virginia, even though enslaved people werent legally allowed to attend. The teacher, a local minister, had shown him how to read and write, and taught him the ways of God. The Christian message of service and humility appealed to him so much that he had begun studying to become a minister himself. Someday, in freedom, he might be able to have a whole Bible of his own, but for now, these copied verses were his lifeline.

He followed the old-timer along the side of the wagon. They were stopped among a copse of slim trees along the road. All was quiet, except for the shuffle of the old white mans feet, the breeze, but William strained his ears for a moment, because there was something else some kind of distant sound at the edge of his hearing. The sound of people, perhaps. A town.

The white man heaved himself into the drivers seat and then patted the spot beside him. Come along.

Sit right next to you? William asked, to be sure. On the wagon bench?

Cant be riding into town with you under a blanket, said the man. Thatd be a mite suspicious, dontcha think?

All right. Williams heart did not slow, but now it was racing for a whole new reason. He climbed up and sat as far to the side as he could, being careful not to touch the white man at all. He surely didnt want to find the limits of the old-timers generosity.

The man nudged the reins and clicked his tongue. Giddyap.

How much further? William asked.

Not far. Put that bag down on the floor, between your knees. Aint nothing gonna happen to it.

William hesitated. The bag had been in his arms for days now. Weeks, perhaps. The journey felt endless.

The old-timer smiled. This is Massachusetts, boy. You gotta start acting free. Cause you are.

William pressed the bag to the floorboards, securing it tight between his feet. He held his head high, and breathed in the word once again. Free.

The wagon rolled on, and soon they were sliding in among the hustle and bustle of the city. Houses and shops, sidewalks and squares. Horses and buggies, people scurrying, some strolling.

William took in every sight. New Bedford was everything he had dreamed of, and more. Faces in the crowd of all colours, moving together in harmony. A far cry from the strict and stilted caste system that rang clear from every angle in Norfolk.

People come here from all over the world, the old-timer said, on the ships at the wharf. William said nothing. His own journey north had started on a boat, out of the dock at Norfolk where he and his father had worked.

His father. A little shiver crossed Williams shoulders. Soon, perhaps, hed be seeing his father for the first time in several years.

Signs in a few of the shops read free labour goods , which the old-timer explained meant they only sold goods that had been produced without using slave labour. Several businesses they passed appeared to be Black-owned. To William, this all seemed too good to be true.

He did a double take at the sight of a white man doffing his hat to a Black woman and stepping out of her way on the sidewalk. William had never seen anything like it. The woman, who dressed in the sort of fancy clothes the lady of the plantation house had worn, nodded politely in kind. The two might have even exchanged a word of greeting. William watched in awe.

He tugged at his own worn-out work shirt, feeling less than ready to face the city, wardrobe-wise. He looked like the field hand and oyster fisherman that he was. That he had been. That was his old life in Norfolk. Here, he could start fresh.

Clothing aside, in every other way he was ready for this new adventure. More than ready. Hed been dreaming about this day for many years, ever since his father had run away to New Bedford, leaving the family behind. He had promised to make the way for William and his mother to follow, or perhaps even to buy their freedom, if he could. Williams mother remained behind, waiting for the day her husband would come for her, but William hadnt wanted to wait any longer.

Freedom demanded a certain impatience, he supposed. Once you had a bug about it in your mind, it was impossible not to grasp the idea with both hands and charge forth. One thing he had learned in his studies freedom would never be simply given. It had to be fought for. And taken.

The old-timer pulled the horse to a stop in front of a small mercantile. It had a free labour sign in the window. Go right on in there now. Tell the owner where ya come from, and hell getcha all set up with yer new papers.

Wait, William whispered. The abolitionist had risked his life to help ferry him to freedom and I dont even know your name.

And ya never will. The old-timer winked and returned his attention to his work horse. Giddyap! The wagon lurched forward, down the street and on into traffic.

William entered the store. The man behind the counter was tall, dark-skinned, with a thick saltand- pepper beard. He was wrapping up purchases in brown paper for a petite Black woman.

You have a nice day, Miss Marlene, the shopkeeper said. As she walked towards the door, he turned to William. Can I help you, lad?