Through meticulous research, Anthony Wood has crafted a fascinating and nuanced account of the rise and fall of Montanas Black communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.... The book reveals how crucial notions of whiteness and white supremacy are to the region and nation.

Laurie Mercier, author of Speaking History: The American Past through Oral Histories, 18652001

In addition to excavating an often erased social history of Black Montanans... Anthony Woods sophisticated use of settler-colonial theories provides a powerful analysis of racial formation, exclusion, and elimination. A work of cuttingedge scholarship, Black Montana is essential reading for those seeking a deeper understanding of the structures of race in the American West.

Jeffrey Ostler, author of Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas

The history of African Americans in the Rocky Mountains is still underdeveloped. Black Montana is important both for its work on bringing attention to the experience of Black Montanans and as a case study in the epistemology of settler colonialism.

Jason E. Pierce, author of Making the White Mans West

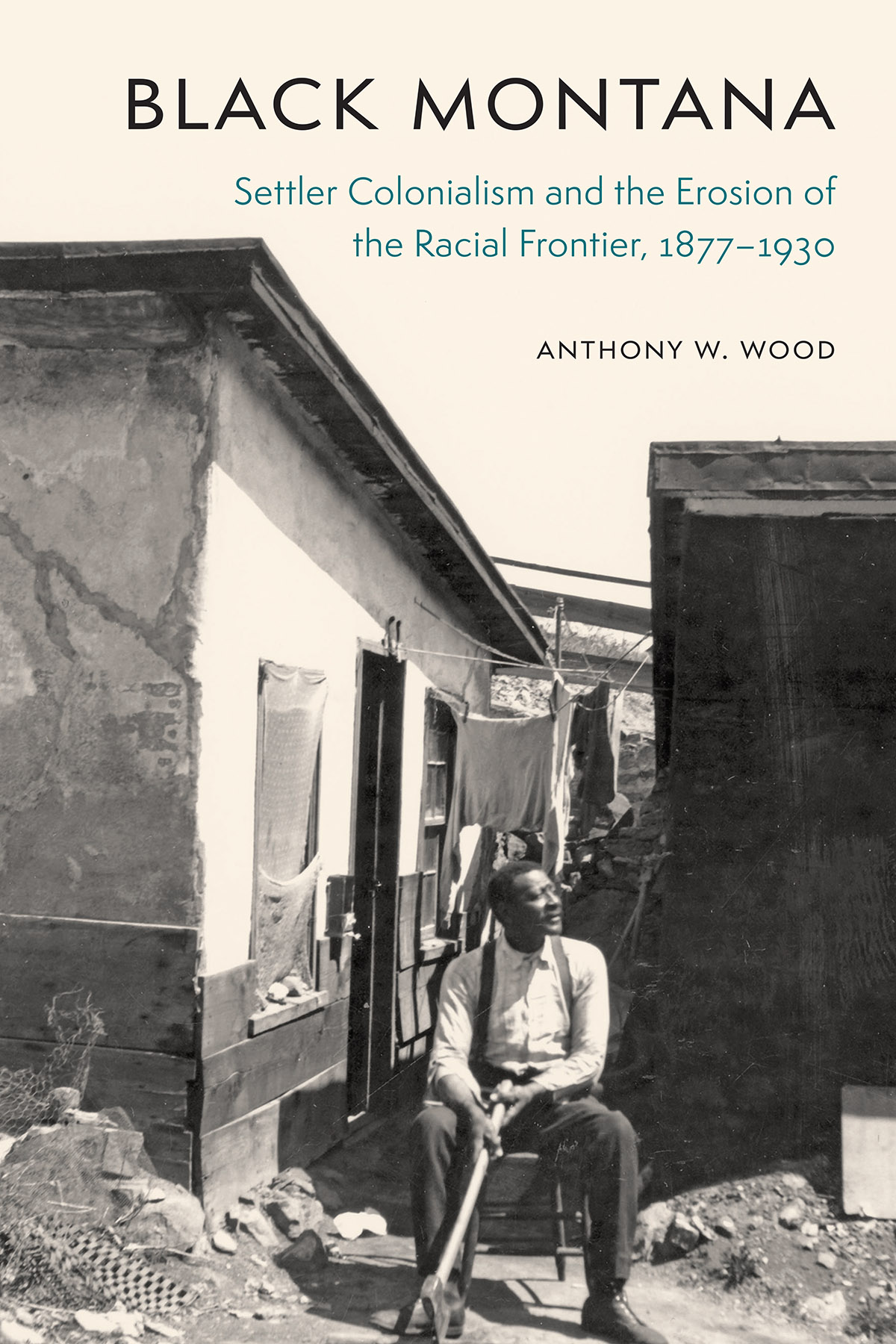

Black Montana

Settler Colonialism and the Erosion of the Racial Frontier, 18771930

Anthony W. Wood

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

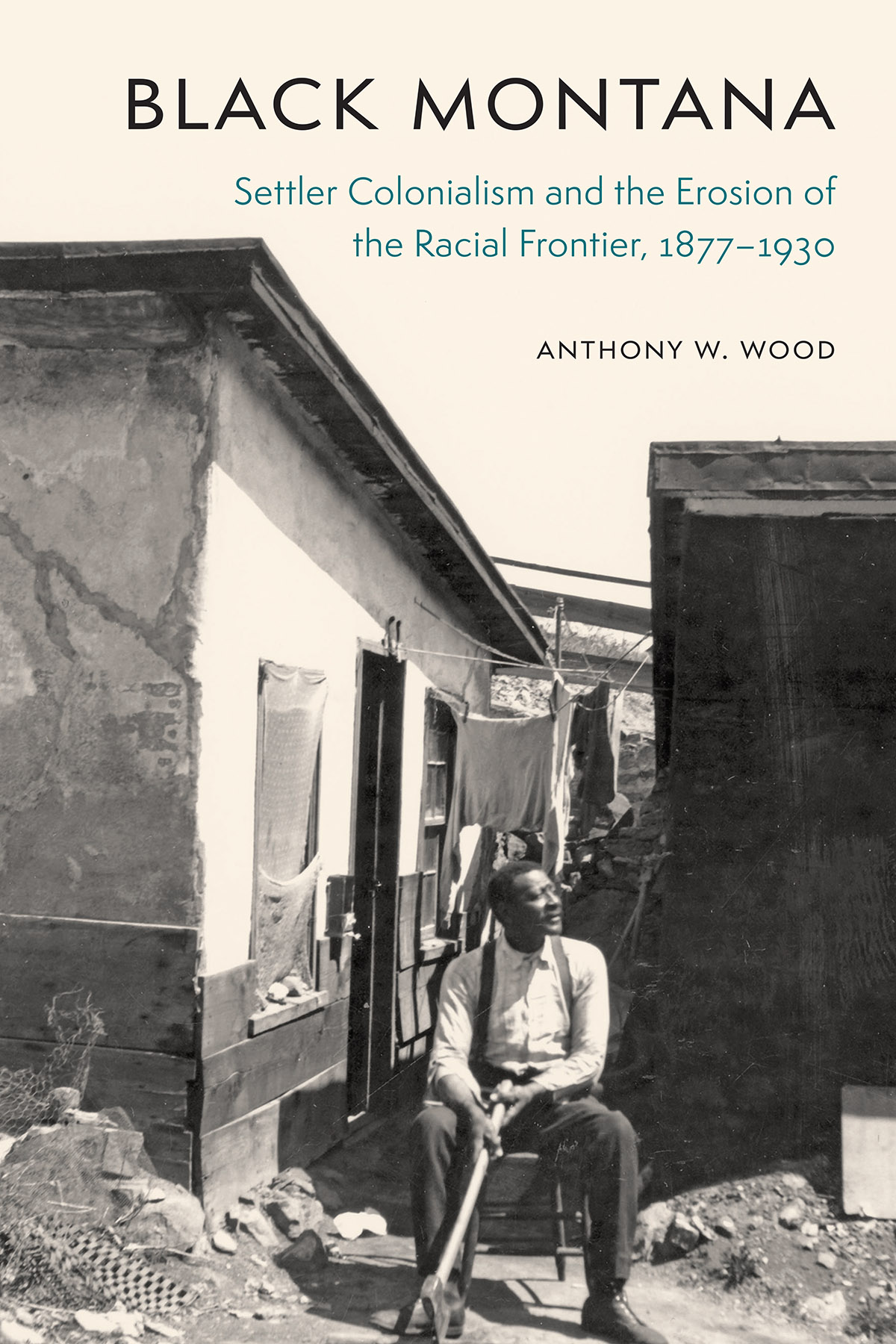

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image: photograph of Jim Jackson by Grace V. Erickson, courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena MT .

Portions of this manuscript originally appeared in After the West Won Montana: The Magazine of Western History 66, no. 3 (September 2018): 3650; and Colonial Erosion: Unearthing African American History in the Settler Colonial West. Settler Colonial Studies 9, no. 3 (Summer 2019): 396417.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wood, Anthony W., author.

Title: Black Montana: settler colonialism and the erosion of the racial frontier, 18771930 / Anthony W. Wood.

Other titles: Erosion of the racial frontier. | Settler colonialism and the erosion of the racial frontier, 18771930

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021. | Revision of the authors thesis. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020041734

ISBN 9781496219435 (hardback)

ISBN 9781496227713 (epub)

ISBN 9781496227737 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : African AmericansMontanaHistory. | African AmericansMontanaSocial conditions. | Race discriminationMontanaHistory. | MontanaRace relations. | Settler colonialism.

Classification: LCC F 740. N 4 W 66 2021 DDC 978.600496/073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020041734

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For my parents, Tom and Mary, who took us to live in the mountains

Contents

Public History and the Birth of an Archive

My work on the history of the Black community in Montana began in the basement of a converted duplex and office building that housed the Montana State Historic Preservation Office ( SHPO ) back in the fall of 2014 (I am happy to say that it has since moved to a beautiful historic building elsewhere on the Capitol campus). At the time, I was still over a year away from receiving my undergraduate degree in history from Carroll College, a small liberal arts school perched atop a hill rising from the capital city of Helena. Working as an intern with SHPO , only twenty years old, and without the type of training that one typically receives in graduate school, I can safely say that I had no idea what I was doing. Luckily, my job consisted at first mostly of sorting through census materials, city directories, historic Sanborn Insurance Maps, and Google Earth images as I tried to locate extant buildings that may have had architectural and historical significance. Perhaps the most fortunate event in my life was returning after graduation to begin my first job as historical researcher for Montanas African American Heritage Places Project ( MAAHPP ).

In the late spring of 2015, my supervisor, Kate Hamptonwho has spearheaded the project since it began in the mid-2000sand I came up with an idea. We envisioned creating maps of all the residences and businesses of the Black community in Helena using several collections of detailed historic insurance maps. If things were done correctly, the aim was to produce a mosaic of turn-of-the-century Helena that would be geographically accurate and then to transpose that map over current satellite imaging. Needless to say, my attempts to stitch together over forty individual sheets of maps using Microsoft Paint both showed my limitations with technology and utterly offended the sensibilities of the SHPO s new geographic information system ( GIS ) specialist, who had just moved into the office upstairs from my basement lair. Luckily my transgression prompted her to offer her expertise to create an actual map that georectified my data and highlighted all the relevant buildings so as to facilitate effortless interpretation. (Considering this was our first interaction, to this day I remain absolutely amazed that she agreed to marry me a year and a half later.)

That map set me on a trajectory that has informed my professional research and graduate studies ever since. For the projects purposes, the map showed over one hundred buildings and houses that were owned or rented by Helenas African American community between 1880 and 1930. Information from the 1900, 1910, and 1930 censuses, over thirty years of Polk City Directories, and a wealth of local knowledge helped map one of the largest and most vibrant Black communities in Montana and the Rocky Mountain West at the time. It quickly became evident that the map also told a more ominous tale than we had anticipated. In the several distinct Black neighborhoods and the lively downtown business district that held dozens of Black enterprises throughout the years, fewer than 20 percent of all houses, tenements, or storefronts once occupied by Helenas African American community now remain. When we eventually mapped the other major Black communities across the state, we saw similarand sometimes much higherpercentages of loss.

Urban renewal initiatives in the 1970s and 1980s removed many buildings from Montanas capital. The targets were, as in many cities, areas of poorer housing, or damaged and neglected commercial buildings. This leveling was preceded by the demolition of dozens of historic homes in Helenas shaded residential quarters during the mid-twentieth century. What the Helena map shows, however, is not the evils of thoughtless development on the part of urban renewal officials or private individuals. It is unlikely that city officials, developers, or owners of historic houses had any idea that the piles of debris they created were once the stores and neighborhoods of Montanas historic Black community. For it was that, by the mid-twentieth century, too few Black residents from that era remained in Helena to fight for their cultural heritage. This was what the map so poignantly spoke tonot the physical removal of the Black community per se, but the ongoing, intangible occlusions of the regions colonial history, scouring the heritage of African Americans from the land as well as their experiences and stories from our collective memory.

Next page