Decolonising Sambo

CRITICAL MIXED RACE STUDIES

Edited by Shirley Anne Tate, University of Alberta, Canada.

This series adopts a critical, interdisciplinary perspective to the study of mixed race. It will showcase ground-breaking research in this rapidly emerging field to publish work from early career researchers as well as established scholars. The series will publish short books, monographs and edited collections on a range of topics in relation to mixed race studies and include work from disciplines across the Humanities and Social Sciences including Sociology, History, Anthropology, Psychology, Philosophy, History, Literature, Postcolonial/Decolonial Studies and Cultural Studies.

Editorial Board: Suki Ali, LSE, UK; Ginetta Candelario, Smith College, USA; Michele Elam, Stanford University, USA; Jin Haritaworn, University of Toronto, Canada; Rebecca King ORiain, Maynooth University, Ireland; Ann Phoenix, Institute of Education, University of London, UK; Rhoda Reddock, University of the West Indies, Trinidad & Tobago

Previously Published:

Remi Joseph-Salisbury, Black Mixed-race Men: Transatlanticity, Hybridity and Post-racial Resilience Winner of the 2019 BSA Philip Abrams Prize.

Forthcoming in this series:

Jennifer Patrice Sims and Chinelo L. Njaka, Mixed-race in the US and UK: Comparing the Past, Present and Future.

Paul Ian Campbell, Identity Politics, Mixed-race and Local Football in 21st Century Britain: Mix and Match.

Decolonising Sambo: Transculturation, Fungibility and Black and People of Colour Futurity

SHIRLEY ANNE TATE

University of Alberta, Canada

United Kingdom North America Japan India Malaysia China

Emerald Publishing Limited

Howard House, Wagon Lane, Bingley BD16 1WA, UK

First edition 2020

Copyright 2020 Emerald Publishing Limited

Reprints and permissions service

Contact:

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. Any opinions expressed in the chapters are those of the authors. Whilst Emerald makes every effort to ensure the quality and accuracy of its content, Emerald makes no representation implied or otherwise, as to the chapters suitability and application and disclaims any warranties, express or implied, to their use.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-78973-348-8 (Print)

ISBN: 978-1-78973-347-1 (Online)

ISBN: 978-1-78973-349-5 (Epub)

Contents

List of Figures and Tables

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Acknowledgements

First, thank you to my family for all of their love and support while I completed this book Encarna, Damian, Soraya, Jenna, Tevian, Lachlan, Arion and Nolan. I also want to thank my sister QT for caring for our mother which gives me the space to do the work.

I want to thank the students in my 2019 course in the Swedish School of Social Science at the University of Helsinki for sharing their knowledge on sambo within their contexts. This gave me the impetus I needed to feel that my ideas on sambo as global were ok.

I want to thank Macarena Gonzlez Ulloa for sharing her photo-text on colonialism in Hamburg with me. This encouraged me to look at Germanys involvement in the slave trade and white settler colonialism. My thanks also go to Beverley Lemire for the coffee in Edmonton and the tip that I should look at Swedens role in enslavement and writing on marble sculptures and racism.

Many thanks to the librarians in the West India Reading Room, Alma Jordan Library, The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Campus, Trinidad and Tobago, for their help with the archival work on sambo on Caribbean slave plantations. I also would like to thank the archivists in El Archivo de Indias in Seville, Spain, for their patience and help in tracking zambo in the Spanish colonial archives. My thanks also go to the library at Nova Southeastern University, Florida, that gave me access for archival work and to Andrea Shaw for enabling this access.

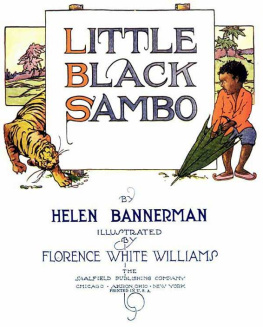

Finally, my thanks to the Carnegie School of Education, Leeds Beckett University, UK, for funding my archival work. I really do appreciate this, as without it the book would not have emerged. Thank you to my colleague Heather Paul, who encouraged me to finish the book when she told me that her constant response to anti-Black racism over the years had to be that she was not that little boy in the blue shorts and red shirt with the green umbrella!

*A version of will apear as Love for the dead: sambo and the libidinal economy of post-race conviviality in M. Griznic and S. Utiz (eds) (2019) Genealogy of Amnesia'.

Chapter 1

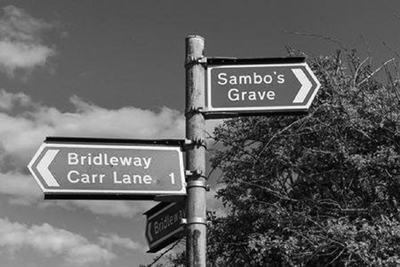

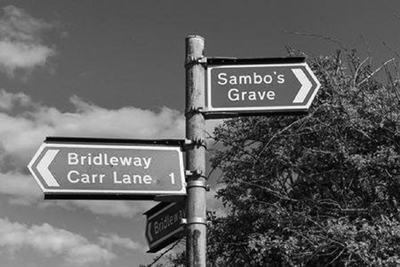

Introduction: Sambos Social Etymology and White European Settler Colonial Transculturation

There it was and I was not even looking for it. After all, why would I want to look for sambo as a descendant of enslaved people in Jamaica? Yet, here it was in Church Square, Cape Town, South Africa. I came across it as I was being taken on a whistle stop tour of the sights, sambo. Writ large on the granite pillars which commanded the location of the colonial slave market. How could it be here when it belonged in the Caribbean, the Americas and the United Kingdom? What had happened? How had it happened and why? This chance encounter led me to engage in an ethnography of looking for sambo through the routes of white European settler colonialism and contemporary culture. This involved voyages both real and metaphorical to Australia, South Africa, Trinidad and Tobago, Florida, Jamaica, Spain, the former Danish West Indies, the Dutch West Indies, as well as parts of the United Kingdom, archival searches, museum artefacts and dipping into popular cultural representations of sambo. I did not do this as a journey where I searched for myself. I simply was not there to be found. Rather, I searched for the white sambo psyche. White European settler colonialisms making of sambo as a category of utter negation into something so normalised that we are inured to it. We can even profess to love it and see it as a part of who we are as nations and people without being troubled by its past or present life. Other people with whom I spoke about the topic of this book found it equally troubling even today because it is a signifier of colonial subjection and present day racist derision. My unease led to this book. As I research and write it is with unease. There is no comfort from sambo. There never was and never will be. No love here but no hate either. Just a studied indifference to this white sambo psyche construction. I begin this journey of looking for sambo with Stuart Halls (1997, p. 7) questions in mind. Do things-objects, people, events in the world-carry their own one true meaning, fixed like number plates on their backs, which it is the task of language to reflect accurately? Or are meanings constantly shifting as we move from one culture to another, one language to another, one historical context, one community, group or sub-culture, to another