Copyright 2003 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2004

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berlin, Ira, 1941

Generations of captivity : a history of African-American slaves / Ira Berlin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-674-01061-2 (alk. paper)

ISBN 0-674-01624-6 (pbk.)

1. SlaveryUnited StatesHistory.

2. SlavesUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title.

E441 .B47 2003

973.0496073dc21 2002028142

Credits

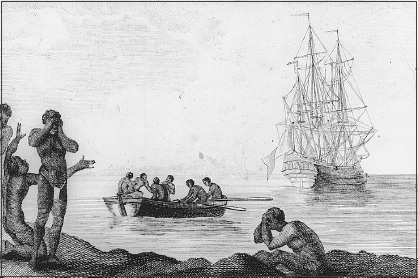

Page 1: March Desclaves from Chambon, Le Commerce de LAmrique par Marseille (1764). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Page 21: The Castle of St. George dElmina from William Bosman, Nauwkeurige Beschryving... (1704). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University. Page 51: The Plantation, artist unknown (c. 1825). Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1963. Reproduced by permission of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. All rights reserved. Page 97: A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, lithograph by David Kennedy and William Lucas (1829). Reproduced by permission of The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Page 159: Slave Trade, Sold to Tennessee, from Lewis Miller, Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia, 1853. Reproduced by permission of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia. Page 245: Arrival of Contrabands at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, from Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861. Courtesy of the Freedmen and Southern Society Project, University of Maryland. Pages viiiix, 22, 52, 98: Graphito. Page 160: Meridian Mapping.

For my brothers, Bruce and Alan They aint heavyFraziers last remarkcalculated to reassure the general and the secretaryspoke to the ministers appreciation of the political realities of the moment. But his definition of slaveryirresistible power to arrogate anothers labordrew on some three hundred years of experience in bondage on mainland North America. Slavery, of necessity, rested on force. It could be sustained only when slaveownerswho, with reason, preferred the title masterenjoyed a monopoly on violence, backed by the power of the state. Without irresistible power, slavery quickly collapsedan event well understood by all those who came together at that historic meeting in Savannah.

Frazier also correctly emphasized the centrality of labor to the enslavement of himself and his people. Plantation slavery did not have its origins in a conspiracy to dishonor, shame, brutalize, or otherwise reduce black peoples standing on some perverse scale of humanityalthough it did all of those at one time or another. Slaverys moral stench cannot mask the design of American captivity: to commandeer the labor of the many to make a few rich and powerful. Slavery thus made class as it made race, and in entwining the two processes it mystified both.

No history of slavery can avoid these themes: violence, power, and labor, hence the formation and reformation of classes and races. The study of slavery on mainland North America is first the study of enormous, hideous violence that a few powerful men wielded to extort the labor of others and thereby attain a place atop American society. The history of slavery, as Thomas Jefferson observed, was a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism. Violence, as Jefferson also understood, begat more violence as slaves refused to surrender what they believed was rightfully theirs. Born of a violent usurpation, slavery wouldand perhaps could onlydie in the same bloody warfare.

The contest between master and slave proceeded on uneven terrain. By definition, relations between masters and slaves were profoundly asymmetrical, with slaveowners holding a disproportion of power and slaves having hardly any. For three centuries, slave masters mobilized enormous resources that stretched across continents and oceans and employed them with great ferocity in an effort to subdue their human property. Slaves, for their part, had little to depend upon but themselves. Yet even when their power was reduced to a mere trifle, slaves still had enough to threaten their ownersa last card, which, as their owners well understood, they might play at any time.

Despite the uneven nature of the contest, slave masters never quite carried the day. While slaveowners won nearly all the great battles, slaves won their share of skirmishes, frustrating the masters grand design. Although denied the right to marry, they made families; denied the right to an independent religious life, they established churches; denied the right to hold property, they owned many things. Defined as property and condemned as little more than beasts, they refused to surrender their humanity. Their small successes and occasional victories, moreover, positioned them to win the last battle. In the end, it was theynot their ownerswho sat at the table with the conquering general and triumphant secretary of war. Yet, even thenas Garrison Frazier and the others understoodthe contest had not ended, for freedom, like slavery, was not made but constantly remade.

Generations of Captivity tells the story of the making and remaking of slavery over the course of nearly three centuries in the portion of North America that became the United States. The emphasis is on the slave. Although slavery was a relationshiphence understanding its working requires an appreciation of slaveowners (large and small), white nonslaveholders, free people of color, and Native Americansthe slave was central to drama. The emphasis is also on change. For too long, scholars have taken the slaves legal status as chattel property and their social standing at the extreme of subordination as evidence that slaves stood outside history. Depicted as socially dead, they became absolute aliens, genealogical isolates, deracinated outsiders, prepolitical, or unreflective sambos who were known for who they were rather than what they did. Appreciating the ongoing struggle between slaves and slaveowners gives the lie to such assumptions. Knowing that a person was a slave does not tell everything about him or her. Put another way, slaveholders severely circumscribed the lives of enslaved people, but they never fully defined them. The slaves historylike all human historywas made not only by what was done to them but also by what they did for themselves.

All of which is to say that slavery, though originally imposed and maintained by violence, was negotiated. Although disfranchised, slaves were not politically inert, and their politicseven absent an independent institutional basiswas as active as any. The ongoing contest forced slaveowners and slaves, even as they confronted one another as deadly enemies, to concede a degree of legitimacy to their opponent. No matter how reluctantly givenor, more likely, extractedsuch concessions were difficult for either party to acknowledge. Masters presumed their own absolute sovereignty, and slaves never relinquished the right to control their own destiny. But no matter how adamant the denials, nearly every interaction of master and slave forced such recognition, for the web of interconnections necessitated a coexistence that fostered grudging cooperation as well as open contestation. The refusal of either party to concede the realities of master-slave relations only added to slaverys instability. No bargain could last for very long, for as power slipped from master to slave and back, the terms of slavery were negotiated and then renegotiated.