About the Author

Norman E. Matteoni is a long-time student of the American West and the life and times of Sitting Bull. Both a legal scholar and practicing lawyer, he has written extensively in law review articles, appellate briefs and a two volume treatise on the Law of Eminent Domain in California. He also is an amateur photographer, and in 2008 he photographed areas of the northern plains, home of the Lakota.

Afterword

By the end of 1890, the Ghost Dance craze was on the wane, but the military would not let the winter months alone exhaust enthusiasm for the religion.

An Indian agent had taken preemptive action, and General Miles, commander of the army overseeing the Plains, was not pleased. The army always took precedence over the bureau in dealing with Indian disturbances. The general had troops on the move to clean up the mess.

In response to anticipated reaction to Sitting Bulls death, army patrols fanned out between the Cannonball and Grand Rivers within Standing Rock, looking for Indian trouble and found none. Rather they located scattered bands of dispirited people.

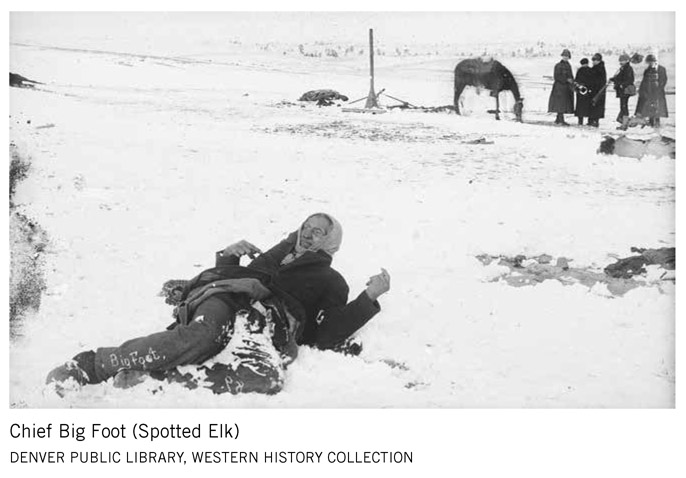

Some of the Grand River Hunkpapas fled immediately after the shootings at Sitting Bulls cabin and sought out Ghost Dance camps in the Badlands area to the south. Big Foot as a key leader of the Ghost Dance movement had been under military observation for some time and he knew it. With Sitting Bull disposed of, Big Foot, Kicking Bear, and Short Bull were marked as the remaining hostile leaders.

Hearing of the great chiefs death, Big Foot took his people toward Pine Ridge, in search of Red Cloud.

Military reconnaissance picked this movement up, and word was dispatched to General Miles. He had previously deployed troops of the 8th Cavalry under Lt. Colonel Edwin Sumner to watch Big Foot. Miles wanted no uprising. Or maybe he did. At a minimum, he was sending a clear signal to the Indian agents that he was in charge; and he played to the hysteria of the whites that had been building. A telegram to the commanding officer at Fort Meade, South Dakota, was sent on December 23 to be delivered in the field to Sumner:

Report about hostile Indians near Little Missouri not believed. The attitude of Big Foot has been defiant and hostile, and you are authorized to arrest him or any of his people and to take them to Meade or Bennett. There are some young warriors that run (sic) away from Humps camp without authority, and if an opportunity is given they will undoubtedly join those in the Bad Lands. The Standing Rock Indians also have no right to be there and they should be arrested. The division commander directs, therefore, that you secure Big Foot and the 20 Cheyenne River Indians, and the Standing Rock Indians, and if necessary round up the whole camp and disarm them, and take them to Fort Meade or Bennett.

The military believed that Big Foots band was headed to the Stronghold to join Short Bull and Kicking Bear. Sumner, who understood Big Foot was close to capitulating and had prior good relations with the man, did not press, allowing the chief time to come in on his own.

Late morning of December 28, Major Samuel Whitsides scouts located the old chief along an icy Porcupine Creek, miles below the Badlands. He only asked for a brief respite to prepare his band for turning themselves over to the military.

It was arranged that he and his people would camp nearby that night and submit to the soldiers the next day. An army ambulance wagon was brought up at the majors order, and Big Foot was transferred into it. He was sent ahead, and his band was moved out under escort. An extreme show of force against a docile camp.

The morning of December 29 was quiet, and the Indians were cooperative as the troopers moved among them. The soldiers seemed not to care that several Indians were wearing ghost shirts. The suppressed emotions of the surrendering Indians flared.

Indians pulled away from the soldiers and some drew knives; soldiers bashed and punched captives with rifles. A man known as Yellow Bird threw dust above his head, which was later reported as a signal for resistance.)

By the afternoon, the sky went gray-white and a northern airstream sent a blizzard over the field of Wounded Knee. Dead Indian bodies were left where they had dropped to freeze in the night. The earth was crusted with bloody snow. In this after stillness, ghosts from lifeless bodies screamed to the sky with no one to hear them.

Four days laterNew Years Day 1891a mass grave was dug by hired civilians, and the corpses were thrown in.

This time from the editors desk of the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer on January 3, 1891, Frank Baum aimed harsh words at Nelson A. Miles: The peculiar policy of the government in employing so weak and vacillating a person as General Miles to look after the uneasy Indians, has resulted in a terrible loss of blood to our soldiers, and a battle which, at its best, is a disgrace to the war department.

Short Bull and Kicking Bear were in the valley of White Clay Creek, about 15 miles north of the agency and were ready to come in. But hearing of Wounded Knee they pulled back.

The last resistance from the mighty Plains Indians was extinguished. Images on glass plate photographs taken during the 1870s and 1880s held only a glimpse of what Sitting Bull tried to preserve.

The Sioux legend that told of Iktomi, the Spider Man spirit or trickster, spreading word that a new man was approaching had come to pass. You shall know him as washi-manu, steal-all, or better by the name of fat-taker, wasichu, because he will take the fat of the land. He will eat up everything, at least for a time.

The prairie was lost.

The frontier was proclaimed closed in 1890 by the United States Census Bureau. Eight hundred miles southeast of the Standing Rock Agency sprawled Chicago, the Midwestern metropolis numbered according to that years national census at over a million persons. It had recovered from the great fire of 1871 and rebuilt itself into Americas second city. Chicago was the site of the nations first skyscraper, supported on an iron frame, rising to nine stories; and a thousand trains came and went from the city each day. This was the industrial and commercial center of the heartland. In April 1890, President Harrison confirmed Chicagos selection as the host city for the 1893 worlds fair, to be known as the Columbian Exposition, commemorating the four-hundredth anniversary of the European discovery of America.

The exposition was powered by alternating-current and illuminated at night by electric street lights. Various exhibits proclaimed the changes forthcoming in the next century, and Professor Frederick Jackson Turner lectured before a convocation of historians on the closing of the frontier. The fairs White City underscored the arrival of the modern industrial age.

For the amusement of the attendees along the midway there was the first Ferris wheel; nearby at the North Dakota Building Sitting Bulls log cabin on the Grand River had been relocated and reconstructed. The reassembled cabin was showcased with the intent to put a period at the end of an era.

Just outside the fairgrounds, Buffalo Bill staged his Wild West show, celebrating life on the frontier that no longer existed. Indians were in urban Chicago, and Custers Last Stand was reenacted as entertainment.

The three great chiefs of the Sioux each had been forced into reservation life. Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull were killed at the hands of their own people on these enclaves. The third, Red Cloud, more willing to seek middle ground, continued to live out his years at Pine Ridge until his death in 1909.