Table of Contents

ALSO BY NATHANIEL PHILBRICK

The Passionate Sailor

Away Off Shore:

Nantucket Island and Its People, 16021890

Abrams Eyes:

The Native American Legacy of Nantucket Island

Second Wind:

A Sunfish Sailors Odyssey

In the Heart of the Sea:

The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

Sea of Glory:

Americas Voyage of Discovery,

the U.S. Exploring Expedition, 18381842

Mayflower:

A Story of Courage, Community, and War

To Melissa

Maybe nothing ever happens once and is finished. Maybe happen is never once but like ripples maybe on water after the pebble sinks, the ripples moving on, spreading, the pool attached by a narrow umbilical water-cord, to the next pool which the first pool feeds, has fed, did feed, let this second pool contain a different temperature of water, a different molecularity of having seen, felt, remembered, reflect in a different tone the infinite unchanging sky, it doesnt matter: that pebbles watery echo whose fall it did not even see moves across its surface too at the original ripple-space, to the old ineradicable rhythm.

WILLIAM FAULKNER, Absalom, Absalom!

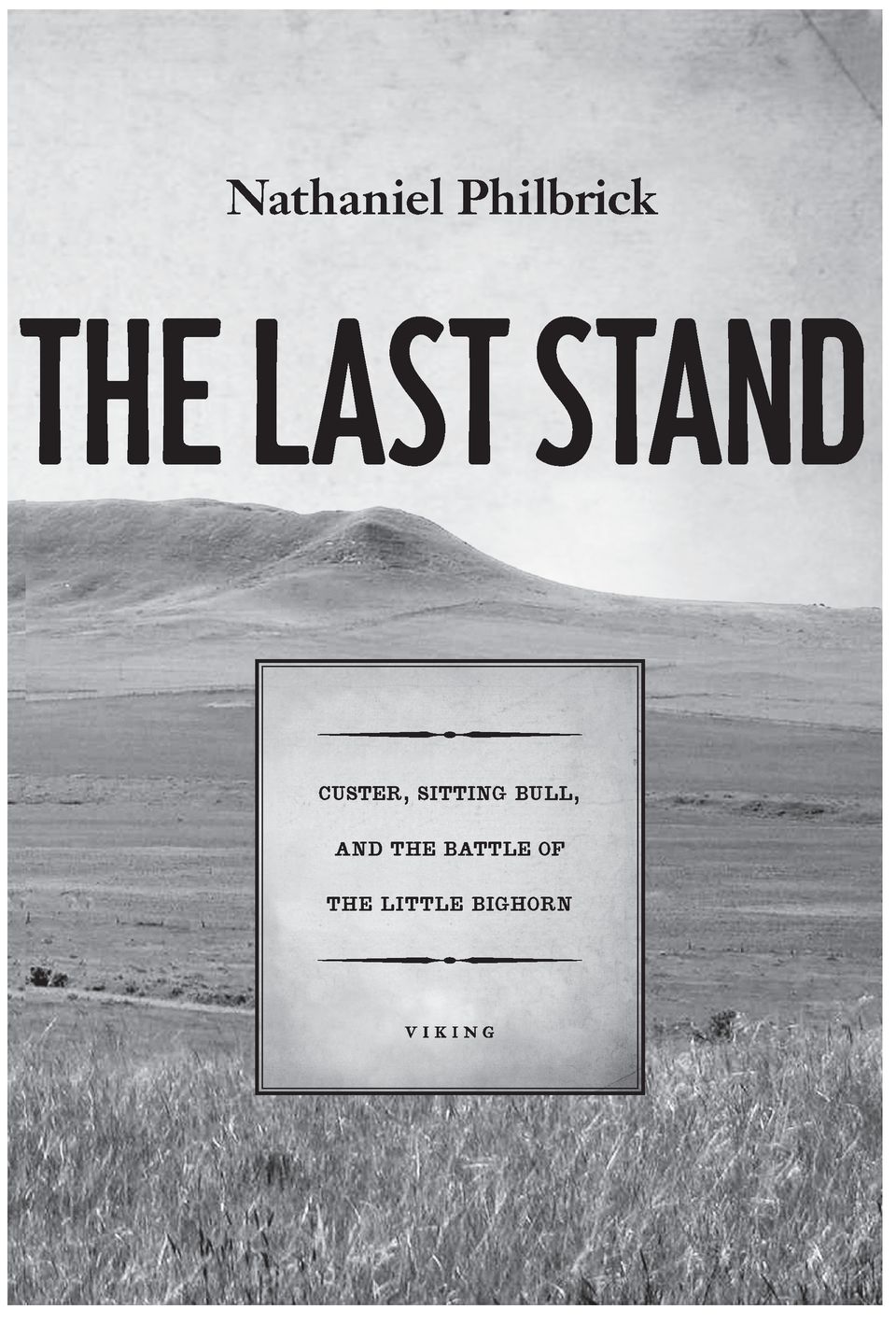

PREFACE

Custers Smile

It was, he later admitted, a rashly imprudent act. He and his regiment were pursuing hostile Indians across the plains of Kansas, a portion of the country about which he knew almost nothing. And yet, when his pack of English greyhounds began to chase some an-telope over a distant hill, he could not resist the temptation to follow. It wasnt long before he and his big, powerful horse and his dogs had left the regiment far behind.

Only gradually did he realize that these rolling green hills possessed a secret. It seemed as if the peak up ahead was high enough for him to catch a glimpse of the regiment somewhere back there in the distance. But each time he and his horse reached the top of a rise, he discovered that his view of the horizon was blocked by the surrounding hills. Like a shipwrecked sailor bobbing in the giant swells left by a recent storm, he was enveloped by wind-rippled crests and troughs of grass and was soon completely lost.

In less than a decade this same trick of western topography would lure him to his death on a flat-topped hill beside a river called the Little Bighorn. On that day in Kansas, however, George Armstrong Custer quickly forgot about his regiment and the Indians they were supposedly pursuing when he saw his first buffalo: an enormous, shaggy bull. In the years to come he would see hundreds of thousands of these creatures, but none, he later claimed, as large as this one. He put his spurs to his horses sides and began the chase.

Both Custer and his horse were veterans of the recent war. Indeed, Custer had gained a reputation as one of the Unions greatest cavalry officers. Wearing a sombrero-like hat, with long blond ringlets flowing down to his shoulders, he proved to be a true prodigy of warcharismatic, quirky, and fearlessand by the age of twenty-three, just two years after finishing last in his class at West Point, he had been named a brigadier general.

In the two years since Lees surrender at Appomattox, Custer had come to long for the battlefield. Only amid the smoke, blood, and confusion of war had his fidgety and ambitious mind found peace. But now, in the spring of 1867, as his trusted horse galloped to within shooting range of the buffalo, he began to feel some of the old wild joy. Amid the beat of hooves and the bellowslike suck and blast of air through his horses nostrils emerged the transcendent presence of the buffalo: ancient, vast, and impossibly strong in its thundering charge across the infinite plains. He couldnt help but shout with excitement. As he drew close, he held out his pearl-handled pistol and started to plunge the barrel into the dusty funk of the buffalos fur, only to withdraw the weapon so as to, in his own words, prolong the enjoyment of the race.

After several more minutes of pursuit, he decided it was finally time for the kill. Once again he pushed the gun into the creatures pelt. As if sensing Custers intentions, the buffalo abruptly turned toward the horse.

It all happened in an instant: The horse veered away from the buffalos horns, and when Custer tried to grab the reins with both hands, his finger accidentally pulled the trigger and fired a bullet into the horses head, killing him instantly. Custer had just enough time to disengage his feet from the stirrups before he was catapulted over the neck of the collapsing animal. He tumbled onto the ground, struggled to his feet, and faced his erstwhile prey. Instead of charging, the buffalo simply stared at this strange, outlandish creature and stalked off.

Horseless and alone in Indian countryexcept for his panting dogsGeorge Custer began the long and uncertain walk back to his regiment.

Like many Americans, I first learned about George Custer and the Battle of the Little Bighorn not in school but at the movies. For me, a child of the Vietnam War era, Custer was the deranged maniac of Little Big Man. For those of my parents generation, who grew up during World War II, Custer was the noble hero played by Errol Flynn in They Died with Their Boots On. In both instances, Custer was more of a cultural lightning rod than a historical figure, an icon instead of a man.

Custers transformation into an American myth had much to do with the timing of the disaster. When word of his defeat first reached the American public on July 7, 1876, the nation was in the midst of celebrating the centennial of its glorious birth. For a nation drunk on its own potency and power, the news came as a frightening shock. Much like the sinking of the unsinkable Titanic thirty-six years later, the devastating defeat of Americas most famous Indian fighter just when the West seemed finally won caused an entire nation to wonder how this could have happened. We have been trying to figure it out ever since.

Long before Custer died at the Little Bighorn, the myth of the Last Stand already had a strong pull on human emotions, and on the way we like to remember history. The variations are endlessfrom the three hundred Spartans at Thermopylae to Davy Crockett at the Alamobut they all tell the story of a brave and intractable hero leading his tiny band against a numberless foe. Even though the odds are overwhelming, the hero and his followers fight on nobly to the end and are slaughtered to a man. In defeat the hero of the Last Stand achieves the greatest of victories, since he will be remembered for all time.

When it comes to the Little Bighorn, most Americans think of the Last Stand as belonging solely to George Armstrong Custer. But the myth applies equally to his legendary opponent Sitting Bull. For while the Sioux and Cheyenne were the victors that day, the battle marked the beginning of their own Last Stand. The shock and outrage surrounding Custers stunning defeat allowed the Grant administration to push through measures that the U.S. Congress would not have funded just a few weeks before. The army redoubled its efforts against the Indians and built several forts on what had previously been considered Native land. Within a few years of the Little Bighorn, all the major tribal leaders had taken up residence on Indian reservations, with one exception. Not until the summer of 1881 did Sitting Bull submit to U.S. authorities, but only after first handing his rifle to his son Crowfoot, who then gave the weapon to an army officer. I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle, Sitting Bull said. This boy has given it to you, and he now wants to know how he is going to make a living.