Also by Paul Williams

The Last Confederate Ship at Sea: The Wayward Voyage of the CSS Shenandoah, October 1864November 1865 (McFarland, 2015)

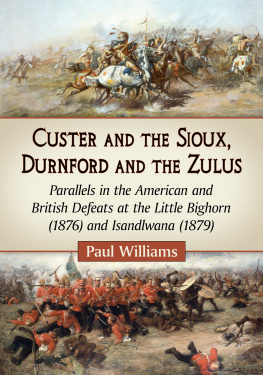

Custer and the Sioux, Durnford and the Zulus

Parallels in the American and British Defeats at the Little Bighorn (1876) and Isandlwana (1879)

Paul Williams

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2032-9

2015 Paul Williams. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: top: The Custer Fight, C.M. Russell, 1903 (Library of Congress); bottom: Battle of Isandlwana, Charles Edwin Fripp, 1885 (National Army Museum)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank a number of helpful organizations, in particular the Nebraska State Historical Society; Library of Billings, Montana; Killie Campbell African Library; Natal Museum; National Army Museum; Royal Engineers Museum; South Wales Borders Museum; Denver Public Library; and the Library of Congress. Also, I would like to thank those who have paved the way with their own research and books over many decades covering the Little Bighorn and Isandlwana.

I would also like to thank the staff at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. During my visit there during the 1980s, I spent a number of days exploring the field of action and attended two public talks by park rangers on separate days. Each ranger went into some detail describing the battle, using the same diorama. But each described a widely dissimilar sequence of events, each purporting to be what did happen rather than what possibly happened. Perplexed, I felt obliged to point out to the ranger that his version was not the one told by his colleague the day before. One member of the audience took exception, stood, and angrily said, You cant say that. Im not sure why he felt this was the case. I replied that I felt the matter, for me at least, needed clarification.

This small clash seemed symbolic of the debate that has gone on ever since the bluecoat defeat at the Little Bighorn and the redcoat defeat at Isandlwana.

Prologue

The triumphant warriors slashed, battered, and hacked the prostrate figures sprawled in the dry, summer grass. Uniforms were stripped off, captured rifles and ammunition hastily gathered, the blood-smeared barrels glinting in the late afternoon sun. The bodies of fallen soldiers and horses were scattered and intertwined, their flamboyant colonel lying dead amid a knot of fallen men. Fingers of ridicule would be pointed at this man, and many would say the blame rested with him. But was it the impossible ultimatum thrust upon the natives by an administration bent on territorial conquest that was at fault? Government and general public alike would be shocked and awed, and all the world would wonder how stone-age men could inflict such a blow. Poems would be written celebrating the regiments heroic stand, and patriotic paintings of soldiers defending their colors to the last would be admired.

But mistakes had been made. Three columns of troops had invaded in an unjust and unprovoked war, misjudging the fighting capacity of the so-called savages who, it was thought, would not stand against a modern army. Bringing the fleeing natives to battle would be the problem. Then the overconfident invaders had compromised their strength by dividing their force, thus allowing the savage annihilation to take place.

And more soldiers not too far distant were at that moment being surrounded by the triumphant warriors. The victors made their way across country, bent on finishing what the days bloody fighting had begun.

This disaster occurred twice. The first time was at the Little Bighorn River, Montana, on June 25, 1876, and the second at Isandlwana, Zululand, on January 22, 1879. The British Army fighting the Zulus had taken no heed of the mistakes made by the army of the United States fighting the Sioux Indians, and a bloody repeat of history was the result.

1

Their Land Is Ours

Ulysses S. Grant was something of an enigma. Who would have believed that the bearded farmer eking out a living selling firewood on the streets of St. Louis in 1855 would, within the next decade, become the nations most celebrated soldier since George Washington and, like Washington, later become president of the United States?

Grants luck changed when the Civil War erupted in 1861. An ex-military officer, he rejoined the Federal army and met with success and eventual promotion to lieutenant general. Four years after the first shots were fired, he accepted the surrender of the Confederate forces under Robert E. Lee. Apart from a few minor engagements and one errant rebel commerce raider sinking Yankee shipping on the high seas, the War Between the States was over.

But the year 1875 found President Grant entangled in a quandary of considerable proportions. The previous year, a military expedition under the command of Lieutenant Colonel (brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer had been sent into the Black Hills of Dakota, part of the Sioux and Cheyenne Indian reservation. The expedition had ostensibly been for military reasons, but prospectors taken along had found traces of gold. Custers report sent back to civilization was cautious, stating, Until further examination is made regarding the richness of gold, no opinion should be formed. Newspapermen taken along, however, gave a more glowing account. Nathan Knappen of the Bismarck Tribune wrote that rich gold and silver mines have been discovered the El Dorado of America. The inevitable rush of fortune seekers was on.

Now there was a demand by many whites that the Black Hills be taken from their rightful owners. But such a seizure would be in violation of United States treaty obligations. The Sioux, or Dakotas, had been the preeminent tribe of the northwestern plains opposing white encroachment on traditional hunting grounds. Now they watched with sullen venom as their sacred Black Hills were desecrated by white miners with no regard for native rights.

Go west, young man, had been Horace Greeleys advice ten years before, when the Civil Wars gruesome battlefields had fallen silent. Helping the immigrant push was the construction of three railroads: the Union Pacific towards California; its eastern division across Kansas to Denver, Colorado; and the Northern Pacific to the Dakota Territories. Here plans were being made for the iron horse to steam out farther onto the northwest plains, following the Yellowstone River through Montana.

Combined with ever-increasing wagon roads, the white mans intrusion dissected the huge buffalo herds and left them open to the prey of many whites, who shot them not only for food and hides, but for sport and other activities, as Custer recalled:

I know of no better drill for perfecting men in the use of firearms on horseback, and thoroughly accustoming them to the saddle, than buffalo-hunting over a moderately rough country. No amount of riding under the best of drill-masters will give that confidence and security in the saddle which will result from a few spirited charges into a buffalo herd.

Next page