All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

TO MY MOTHER, ALYCE HELEN CARMEN, WHO NIGHTLY FROM AN OLD BLACK BINDER READ HER FAVORITE STORY POEMS, HAND-COPIED, TO HER FOUR CHILDREN:

THE BOY STOOD ON THE BURNING DECK...

SOURCES AND ACCURACY

I have relied on primary accounts (rather than secondary accounts, interpretations, or hearsay) almost exclusively in the following narrative. But not all such accounts are created equal, and I have tried to be rigorous in their use. The just-surrendered Lakota leader fearful of retribution; the trooper or warrior whose faulty memory attempts to remember events of fifty or more years ago; the officer concerned with avoiding blame and thus subtly altering his version of those same events the difficulties inherent in these kinds of accounts and others, such as faulty interpreters or overly dramatic reporters, have complicated the job of anyone trying to find the truth of what happened along that river on June 25, 1876. Combined with the all-too-human propensity for viewing and remembering the same event differently, the historians task in this case is made surprisingly difficult considering the multitude of eyewitness accounts. Fortunately, the broad brushstrokes of history here are not in question, though many of the details certainly are. In such instances, where there is disagreement over what occurred, I have endeavored to examine the evidence objectively before making a decision as to the most likely course of action. (Any such examinations or discussions, moreover, are confined to the notes.)

All dialogue appearing within quotation marks comes directly from primary sources accounts written or given by eyewitnesses or others who interviewed them. Those sources include trial transcripts, letters, interviews published in newspapers, et cetera, and unpublished participant interviews and accounts.

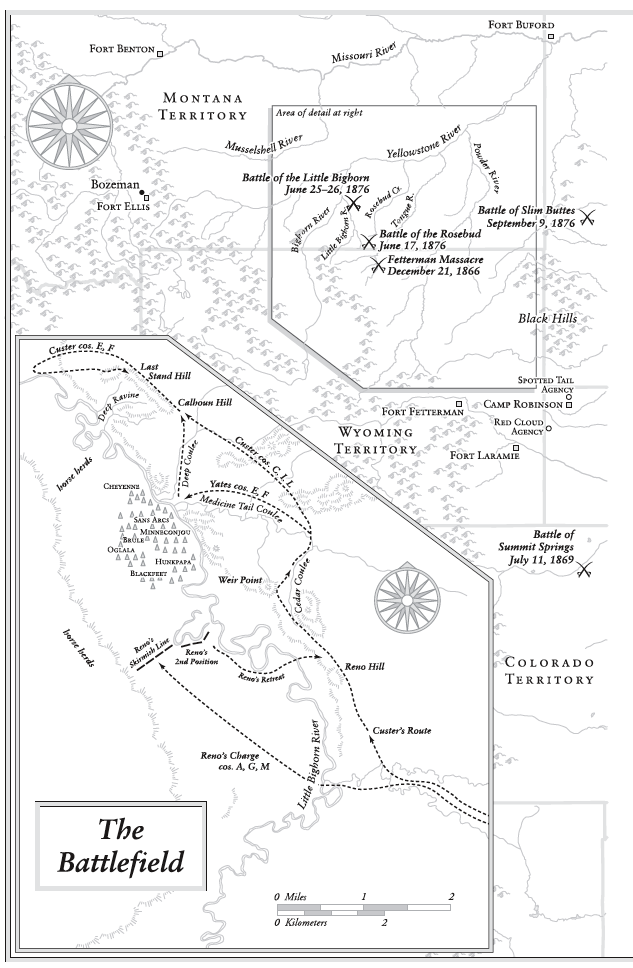

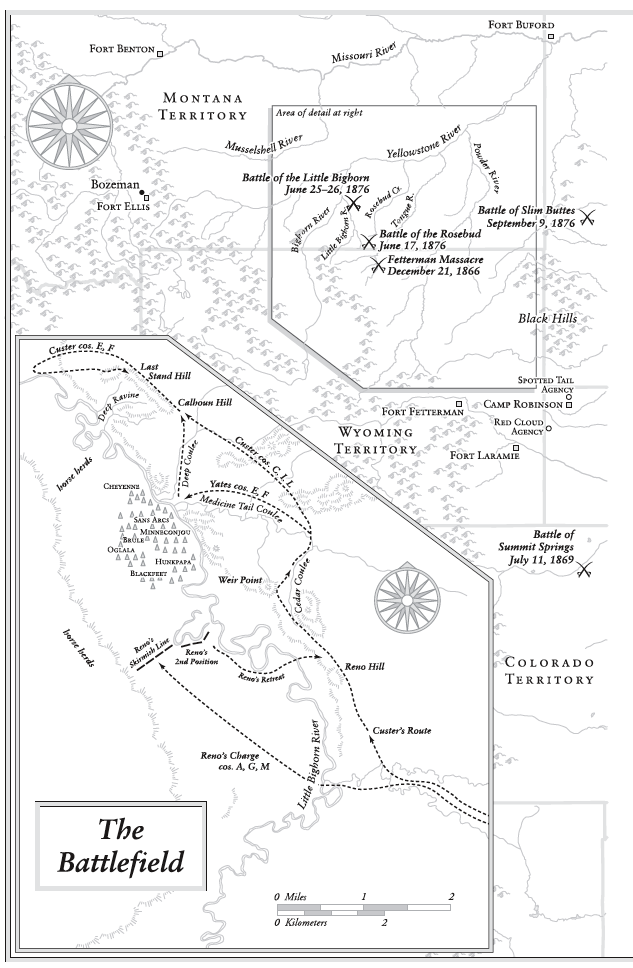

In only one area have I employed anything other than the strict historical record: that part of the battle dealing with the movements of Custers battalion after trumpeter John Martin gallops away with a message from his commander as Custer leads his men down into Medicine Tail Coulee. We will never know, without a reasonable doubt, what happened to Custer and his 210 men. That is because no white observer saw any man of that contingent alive again, and the accounts of those who witnessed its movements the Sioux and Cheyenne who defeated Custer are, for many reasons, sketchy and often contradictory. But there is knowledge to be gleaned from a careful sifting of those accounts. The stories of those eyewitnesses, checked against each other and against the known positions of the troopers bodies and the extensive archaeological and forensic work completed over the last quarter century, enable one to determine, to a reasonably accurate degree, the actions (and by extension some of the thoughts) of Custer and a few of the men in his battalion. Though others may interpret the same record differently, I believe that given the information available, the actions of Custer and his subordinates as related herein during that time are those most likely to have occurred.

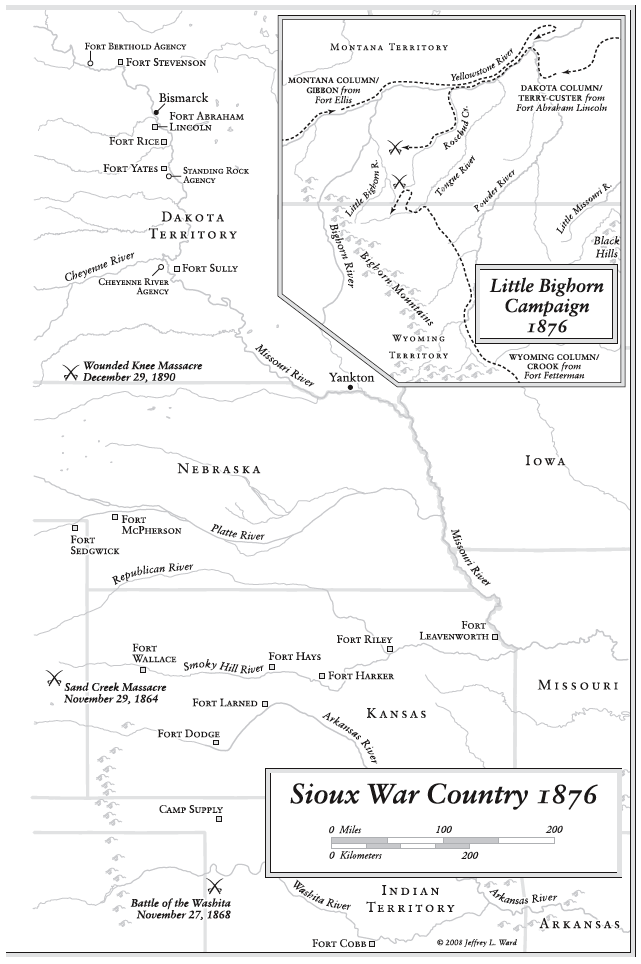

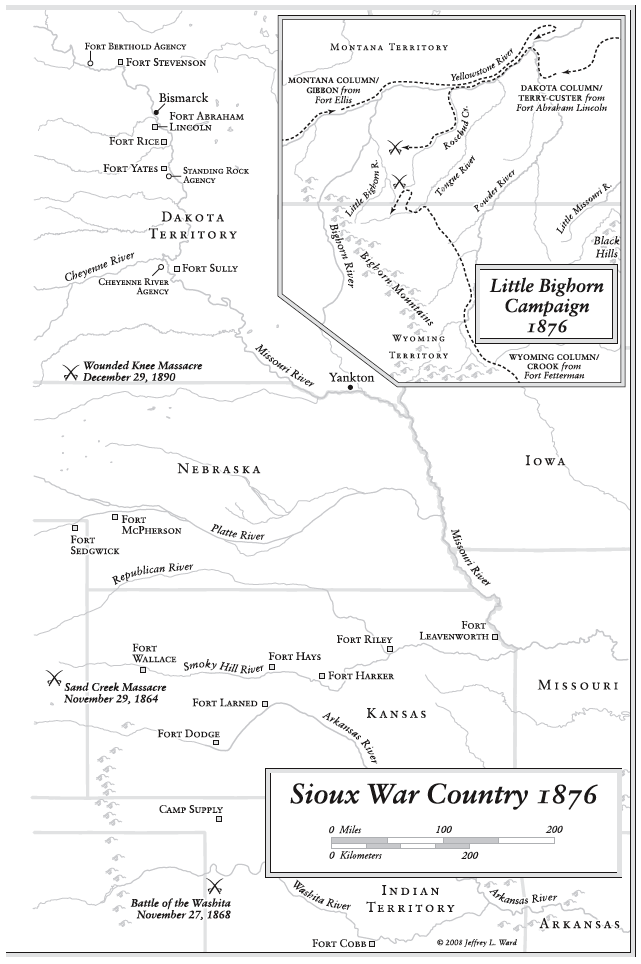

SIOUX TRIBAL STRUCTURE

The people known to the whites as Sioux were divided into three related groups, each of which spoke a slightly different dialect. The largest and westernmost were the Lakota (Teton), consisting of seven major tribal divisions (Hunkpapa, Oglala, Minneconjou, Brul, Blackfeet, Two Kettle, and Sans Arcs) that lived west of the Missouri River and north of the Platte River. The easternmost group were the Dakota or Santee (further divided into the Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute, and Sisseton), in Iowa and Minnesota west of the Red River. Between them between the Missouri and the Red Rivers were the Nakota or Yankton (comprising the Yankton and Yanktonai). There are many variant spellings of some of these (Uncpapa, Minnecoujou, and so forth), and there are also Siouan versions. In almost every case, I have employed the most common and traditional forms for familiarity, regularity, and simple ease of reading.

ARMY RANK

During the Civil War, a Union officer could actually hold as many as four ranks: his permanent (full) rank in the Regular Army, a full rank in the Volunteers, and brevet ranks in both. A brevet rank was an honorary promotion given an officer for battlefield gallantry or meritorious service and was often awarded for much the same reasons medals are given out today (our modern system of medals did not exist until several decades after the Civil War). After the war, when the Volunteer army was disbanded, brevet promotions were still awarded, but less frequently. Though except in rare instances it imparted little authority and no extra pay, an officer was entitled to be addressed by his brevet rank. For the sake of clarity, I have refrained from that practice with one exception. Despite his Regular Army rank of Lieutenant Colonel, George Armstrong Custer was referred to by one and all of the men under him as the General, in honor of his Civil War brevet ranks of Major General in both the Regular Army and the Volunteers. I have followed that custom frequently in this book.

A Good Day to Die

Wolf Mountains, Montana Territory June 25, 1876, 3:00 a.m.

T he night was pitch-black and cool as the small party of scouts reined their horses off the creek and up into the hidden hollow between the hills. They picked their way through juniper trees, up the westernmost ridge, until it became too steep for horses. Second Lieutenant Charles Varnum dismounted, threw himself on the ground, and fell asleep instantly. The young West Pointer had ridden close to seventy miles since early that morning, almost twenty-four hours nonstop. He was bone tired.

All six of the Arikara Indians followed the officers lead, for they had been in the saddle just as long. But two of the five Crow Indians, along with the dapper scout Lonesome Charley Reynolds, left their horses and climbed the steep slope to a ridge overlooking the pass that crossed the divide between the Little Bighorn and Rosebud valleys. The Arikaras were only along as couriers; their homeland lay on the Missouri River, almost three hundred miles to the east. This was Crow country, and the Crows had often used the hollow to conceal their horses while scouting the area during Sioux pony raids. From the lookout, they could usually see for a great distance in both directions. But not this night, not now. The thin crescent moon had set before midnight, and only starlight illuminated the sky.

An hour later, the diminutive half-breed guide Mitch Boyer shook Varnum awake. There was light in the sky, and the Crows wanted their chief of scouts on the hill. The hatless Lieutenant he had lost his hat fording a stream along the way and the scouts scrambled up through the buffalo grass to the top.