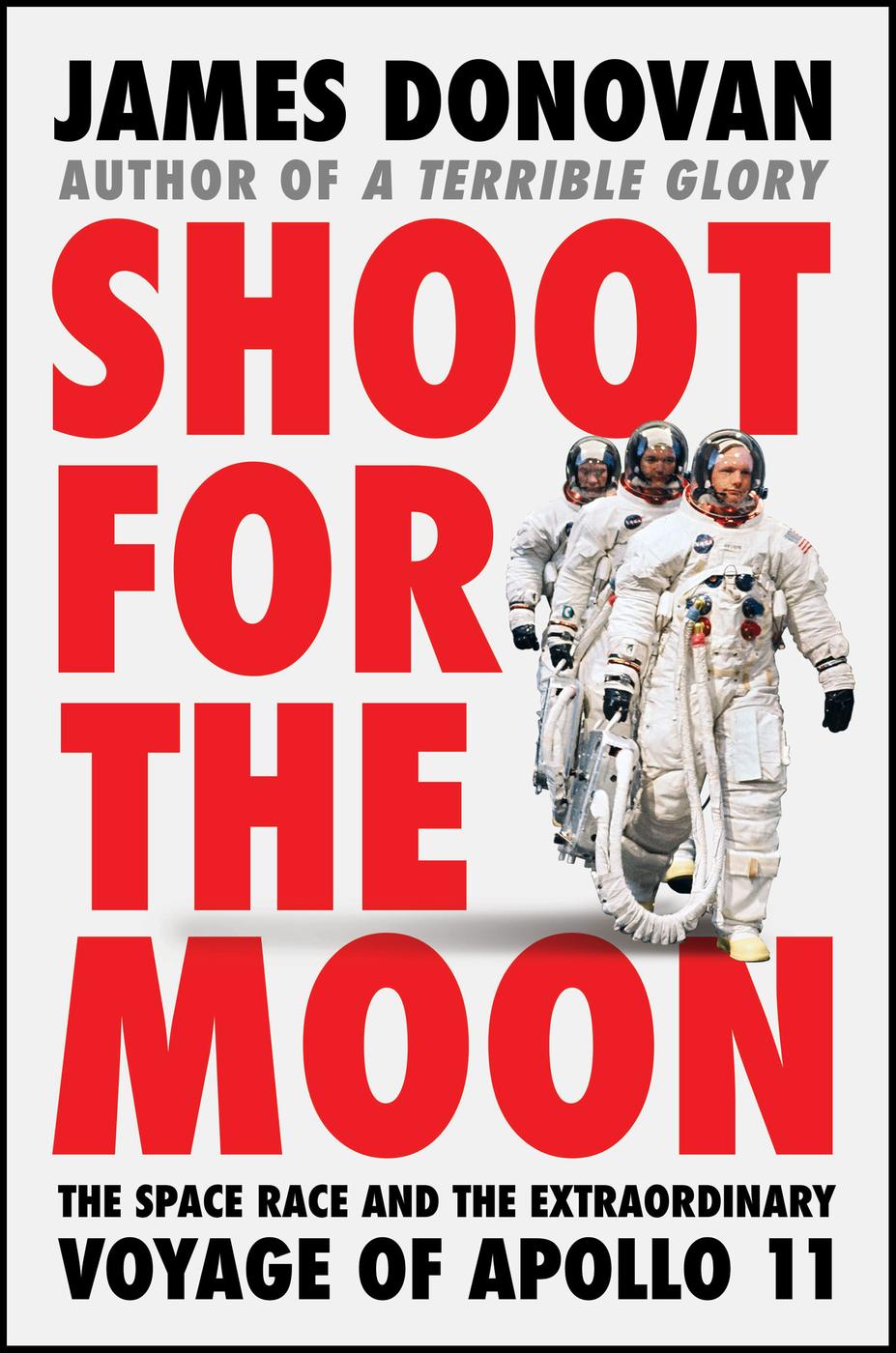

Copyright 2019 by James Donovan

Cover design by Gregg Kulick

Cover photograph by Mondadori Portfolio

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

First Edition: March 2019

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

All photographs courtesy NASA unless otherwise stated

ISBN 978-0-316-34182-0

E3-20190201-DA-NF-ORI

For my sister and brothers,

in memory of a Brooklyn room with four beds:

Whenever the moon and stars are set

Neither the sun nor death can be looked at steadily.

Franois de La Rochefoucauld

Cape Kennedy, July 16, 1969, 4:15 a.m.

The beastwhat some early missile men called a rocketstood on thelaunchpad, dozens of spotlights bathing its milky-white skin, hissing, groaning, gurgling, thick umbilical hoses pumping fuel into it, sheets of ice sliding down its sides from the super-chilled liquid oxygen inside, some of it boiling off in thick white clouds of breath, and looking as if it might shake off the arms of its gantry, rip itself from its moorings, and stalk off down the Florida coast.

Eight miles away, on the third floor of Kennedy Space Centers Building 24, Deke Slayton walked down the hall of the crew quarters and rapped on three doors. With each knock, he said cheerily, Its a beautiful day, and he meant it.

Raised on a farm, the unpretentious Slayton was fiercely protective of his chargespart den mother, part dictatorwhile at the same time envious of every one of them. A former World War II bomber pilot and test pilot and an original Mercury Seven astronaut, hed been made chief of NASAs astronaut office when a minor heart problem grounded him before he had a chance to fly a mission into space. Slayton understood better than anyone that to a certain extent, the mens fates were in his hands, since he selected the crew for each mission and could make or break their careers. He was scrupulously fair in his choicesfor the most part.

The men behind the three doors were astronauts Neil Armstrong, Edwin Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins. They constituted the crew of the Apollo 11 scheduled for launch that morning. In three hours, they would climb into a small chamber atop the 363-foot, three-stage Saturn V, the most powerful machine ever built, and blast off into space. A few days later, two of them would attempt to do something that had never been done before: pilot a small, fragile craft down to another world, 239,000 miles from Earth, and walk on its surface.

These three men and others, most of them culled from the ranks of the nations top test and fighter pilots, had committed their lives to this goal and worked tirelessly toward this moment.

When the American space program began, in 1958, no human had journeyed into the hostile environment of spacean airless, low-gravity vacuum with temperatures of extreme cold and intense heat that no living being could withstand. Without an artificial life-support system, a man would die instantly. Even with one, he might die; the effects of weightlessness, radiation, meteors, and the enormous forces accompanying launch and reentry were largely unknown. Each astronaut had trained for years to overcome these dangers and others.

Along the way they also spent thousands of hours learning how to use the machines that would carry them into space, machines far more sophisticated and complex than any previously invented, machines designed by a cadre of visionary scientists and engineers united by a dream of space travel, an insatiable curiosity, and the determination to make that dream come true. They all worked insanely long hours, often at the expense of their personal lives and relationships. Along with the four hundred thousand other men and women who actually built the machines, the astronauts devoted themselves to helping their country triumph against the Communist threat. At stake was not just supremacy in space but quite possibly Americas survival as a democracy.

They had not reached this point without major setbacks and great tragedies. Rockets exploded. Systems malfunctioned. Men died. The murder of a visionary president whose bold challenge had fired the program only reaffirmed their dedication to finishing the job.

But in October 1957, still flying high just a dozen years after their victory in World War II, Americans had no idea how a small metallic ball with a radio transmitter would change the world.

Our aim from the beginning was to reach infinite space.

Major-General Walter Dornberger,

coordinator of Germanys V-2 program

One Saturday morning in October 1957, a fourteen-year-old boy in the small farming town of Fremont, Iowa, woke up to find the world a different place. The Soviet Union had launched a beach-ball-size silver sphere into orbit around the Earth. They called it Sputnikliterally, fellow traveler. The Russians, those steppe-riding, vodka-swilling Cossacks who were widely seen as a second-rate technological power, had beaten the United States into space.

The boys name was Steve Bales, and he was of average height with thick brown hair and glasses. His mother worked in a beauty parlor, and his father, who at the age of thirty-nine had been drafted into the U.S. Army and served with the 102nd Infantry Division in World War II, owned a hardware store. Steve told his parents, his three younger brothers, and anyone else whod listen how angry he was that America hadnt launched a satellite first. Hed been interested in space ever since he was ten, when he and his father and brothers spent many a summer night sleeping outside on well-worn gray blankets in the field behind their house on the edge of town. As darkness fell, their dad would point out the Big Dipper, Cassiopeia, and other constellations, and nothing seemed as wonderful as the universe and its mysteries. That excitement spiked when the boy watched a 1955 Walt Disney TV special that featured an intense rocket scientist with a slight German accent describing how one day man would reach the moon.

Now there was an artificial satellite, and it belonged to the Sovietsthe enemy in this Cold War. But it was only a matter of time, the boy knew, before the United States would launch its own, and there would be more space exploration. And he wanted to be a part of it.

Lyndon Johnson, Senate majority leader, was relaxing with some friends at his family ranch in the Texas Hill Country that Saturday, October 5, when he heard about Sputnik. After dinner, they took a walk down a dark road, and everyone looked up at the sky. In some new way, Johnson remembered, the sky seemed almost alien. He spent most of that evening calling aides and colleagues, mobilizing them to begin an inquiry into the nations satellite and missile programs. Johnson knew more about this new frontier than any other elected official in Washingtonhe had been spearheading congressional hearings and inquiries into Americas space programs since the late 1940sand he didnt like the feeling of being second to Americas greatest enemy. He wanted to respond immediately to the Soviet challenge, and he began plans to chair a Senate Preparedness Subcommittee. It was clear to him that a comprehensive space program was necessary. That the Eisenhower administrations ineptitude in space provided an opportunity for political gainso much the better.