ABOUT THE BOOK

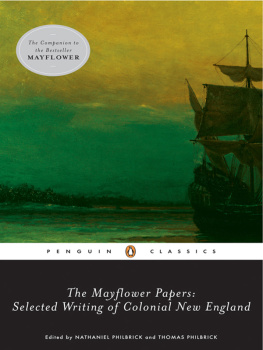

One of Americas most acclaimed historians takes on the nations First Thanksgiving, telling us the true story behind the tale we think we know so well. In this selection from the New York Times bestselling Mayflower, Nathaniel Philbrick recounts in riveting detail the truth about relations between Plymouth Colony and the British crown and between the colonists and Native American tribes, and he shines a light on the courage, communities, and conflicts that shaped one of our countrys most celebrated national holidays.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright 2006 by Nathaniel Philbrick

Map copyright 2006 Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward

The contents of this book first appeared in Nathaniel Philbricks Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War (Viking Penguin, 2006; Penguin Books, 2007)

ISBN 978-1-101-63091-4 (eBook)

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Preface

W E ALL WANT TO KNOW how it was in the beginning. From the Big Bang to the Garden of Eden to the circumstances of our own births, we yearn to travel back to that distant time when everything was new and full of promise. Perhaps then, we tell ourselves, we can start to make sense of the convoluted mess we are in today.

But beginnings are rarely as clear-cut as we would like them to be. Take, for example, the event that most Americans associate with the start of the United States: the voyage of the Mayflower.

Weve all heard at least some version of the story: how in 1620 the Pilgrims sailed to the New World in search of religious freedom; how after drawing up the Mayflower Compact, they landed at Plymouth Rock and befriended the local Wampanoags, who taught them how to plant corn and whose leader or sachem, Massasoit, helped them celebrate the First Thanksgiving. From this inspiring inception came the United States.

Like many Americans, I grew up taking this myth of national origins with a grain of salt. In their wide-brimmed hats and buckled shoes, the Pilgrims were the stuff of holiday parades and bad Victorian poetry. Nothing could be more removed from the ambiguities of modern-day America, I thought, than the Pilgrims and the Mayflower.

But, as I have since discovered, the story of the Pilgrims does not end with the First Thanksgiving. When we look to how the Pilgrims and their children maintained more than fifty years of peace with the Wampanoags and how that peace suddenly erupted into one of the deadliest wars ever fought on American soil, the history of Plymouth Colony becomes something altogether new, rich, troubling, and complex. Instead of the story we already know, it becomes the story we need to know.

In 1676, fifty-six years after the sailing of the Mayflower, a similarly named but far less famous ship, the Seaflower, departed from the shores of New England. Like the Mayflower, she carried a human cargo. But instead of 102 potential colonists, the Seaflower was bound for the Caribbean with 180 Native American slaves.

The governor of Plymouth Colony, Josiah Winslowson of former Mayflower passengers Edward and Susanna Winslowhad provided the Seaflower s captain with the necessary documentation. In a certificate bearing his official seal, Winslow explained that these Native men, women, and children had joined in an uprising against the colony and were guilty of many notorious and execrable murders, killings, and outrages. As a consequence, these heathen malefactors had been condemned to perpetual slavery.

The Seaflower was one of several New England vessels bound for the West Indies with Native slaves. But by 1676, plantation owners in Barbados and Jamaica had little interest in slaves who had already shown a willingness to revolt. No evidence exists as to what happened to the Indians aboard the Seaflower, but we do know that the captain of one American slave ship was forced to venture all the way to Africa before he finally disposed of his cargo. And so, over a half century after the sailing of the Mayflower, a vessel from New England completed a transatlantic passage of a different sort.

The rebellion referred to by Winslow in the Seaflower s certificate is known today as King Philips War. Philip was the son of Massasoit, the Wampanoag leader who greeted the Pilgrims in 1621. Fifty-four years later, in 1675, Massasoits son went to war. The fragile bonds that had held the Indians and English together in the decades since the sailing of the Mayflower had been irreparably broken.

King Philips War lasted only fourteen months, but it changed the face of New England. After fifty-five years of peace, the lives of Native and English peoples had become so intimately intertwined that when fighting broke out, many of the regions Indians found themselves, in the words of a contemporary chronicler, in a kind of maze, not knowing what to do. Some Indians chose to support Philip; others joined the colonial forces; still others attempted to stay out of the conflict altogether. Violence quickly spread until the entire region became a terrifying war zone. A third of the hundred or so towns in New England were burned and abandoned. There was even a proposal to build a barricade around the core settlements of Massachusetts and surrender the towns outside the perimeter to Philip and his allies.