Rosebud

In the early 1900s, after trekking with horse and wagon and other livestock from Unionville, Missouri, to Dupree, South Dakota, my grandfather, Alonzo Grant Davis, always known as A.G. Davis, and his five young children settled down on government homesteaded land and commenced, under severe conditions, to create a farm out of previously untilled landscape. My grandmother, Laura Bradshaw Davis, had died soon after giving birth to her last child. My father was her third, and was eleven years old at the time of her death. My aunt Hazel was the eldest and consequently inherited the role of mater familias. Even my father confessed that she raised us all.

The A.G. Davis family brought with them to South Dakota many Southern characteristics. Although Unionville is only a few miles from Iowa, and Missouri has always been a border state, their southern orientation is not particularly surprising since they were descendants of one John Davis who emigrated from Wales, finally settling in western Virginia, or what is now Kentucky, early enough to have joined the Continental Army in Albemarle County, and to have chased Cornwallis troops, so he claimed, up and down the Atlantic coast. He and a brother, James, were also present at the surrender ceremony at Yorktown, before returning to his farm in Kentucky. Applying for his wartime pension, he was required to prove his service, and since there were no official discharge papers issued at that time, he obtained the written testimony of several neighbors who swore that he was indeed a soldier of the revolution.

My grandfather himself came from a rather large family, he being the youngesttoo young apparently to have served during the Civil War, though several of his older brothers did. Since his middle name was Grant , I have always supposed that he was named after General Ulysses S. Grant. Apparently a schism developed in the family. I am not at all sure but I suspect that some in the family supported the Confederate cause and others the Union. In any case, I remember my mothers telling of a nostalgic trip which my parents and my grandfather took back to the old homestead in Missouri. Driving out to the farm or to the farm house of one of his daughters, my grandfather recognized the driver of another vehicle and identified him as one of his brothers, but declined to stop, even to say hello. My mother could never understand his attitude or behavior on that occasion. She guessed that it was just a Davis thing. Possibly it was just his expression of a residual resentment relating to Civil War loyalties.

Although a very hardworking man, extremely devoted to the well-being of all his children, his blood-kin as he put it, as honest as anyone in Ziebach county, and much respected, he was nevertheless a racist in the sense that he believed blacks to be inferior in all respects to whites. Not that he disliked blacks or wished to deny them their rights, but he couldnt escape that pre-Civil War southern master-slave mentality. He once told me while visiting our family in Minneapolis, Minnesota, that whenever he was in strange or unfamiliar place he had no hesitancy in asking directions or other information from a black person, or negro, which was the term he used. I dont recall that he ever used the derogatory n word. The reason he gave was that blacks were always polite and properly subservient, something he could not always count on in a white man.

After service in the United States Navy (191718), my father returned to South Dakota, and for a time acquired and worked a homestead of his own. All that was required for this relatively free land was a structure one could live in and an agreement to work the land for a minimum length of time. After a while, however, he was lured to the Rosebud Reservation to serve as Farm Agent. Perhaps a word of explanation regarding this job of teaching Indians how to be farmers needs to be given.

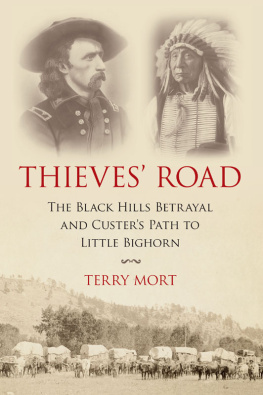

As far back as Thomas Jefferson it was Administration policy to convert Indians from hunters and gatherers to farmers. Jefferson foresaw even then that the depletion of wildlife and the destruction of forests for agricultural purposes by white settlers had, or soon would, make it impossible for the Indians to live as they previously had. Of course this was prior to the doubling of the size of the country by the Louisiana Purchase and the discovery by Lewis and Clark of literally millions of buffalo on the western plains. In time, of course, professional buffalo hunters such as William F. Cody, alias Buffalo Bill, would decimate such herds, partly for their meat and hides, but often and licentiously for the hell of it. The U. S. Cavalry which was later sent, after the Civil War, to protect settlers from Indian raids, were also responsible for much killing of the buffaloes. Even friendly Indians would kill buffalo for their hides to sell to the Army, leaving the carcasses to rot on the open plains. Custer enjoyed the sport and once expressed the view that hunting buffalo was as exciting as hunting Indians. (Ambrose, 327)

After the Great Indian Wars, one of Custers primary duties was corralling Indians and forcing them by deceit or calculated violence to live on reservations. The Brul Sioux, otherwise known as Sicangu Sioux, were herded onto the Rosebud Reservation, established in 1889, located in south central South Dakota bordering the State of Nebraska. It later became my fathers task to teach them how to farm dry prairie land. Average rainfall in South Dakota in the Rosebud area averages about 13 to 14 inches a year. The U. S. Government through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was supposed to supply the implements, plows, hoes, etc., and the initial seed. My father who had grown up as a farmer was fully qualified to perform this task. However, the plan never succeeded. The Plains Indians disliked the occupation and were reluctant to give it a try. Some persons have supposed that being inherently nomadic the idea of turning Indians into farmers was bound to fail. In fact, however, eastern tribes often grew crops. The tribes of Massachusetts taught the Pilgrims how to grow maize or corn, and in fact saved their lives by teaching them how to survive on what was to them unfamiliar land.

Jeffersons policy was entirely reasonable and indeed prescient with respect to American Indians nationwide. The problem lay with its implementation. As Arapaho Councilman Crawford White, a farmer in the Southwest succinctly expressed it,

The white man placed us here and told us to survive, to change our traditional lives as hunters and become farmers. But then he took away much of our water, so white settlers could feed their crops. Now there are not enough jobs for everyone. So are we to give up our land and leave the reservations? For people who have lived here all their lives, that is not an easy thing to do. (see Mark Wexler, Sacred Rights, National Wildlife Magazine, June/July, 1992, 21).