With the Dakota Sioux Indians: Writings FromCharles Eastman (Ohiye Sa)

Edited and with Introduction by LennyFlank

Copyright 2009 by Lenny Flank

All rights reserved

Smashwords ebook edition.

Red and Black Publishers, PO Box 7542, StPetersburg, Florida, 33734

http://www.RedandBlackPublishers.com

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personalenjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away toother people. If you would like to share this book with anotherperson, please purchase an additional copy for each person youshare it with. If youre reading this book and did not purchase it,or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should returnto Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you forrespecting the hard work of this author.

Contents

Editors Preface

Indian Boyhood

Indian Heroes and Great Chiefs

The Soul of the Indian

Sioux Folktales Retold

Editors Preface

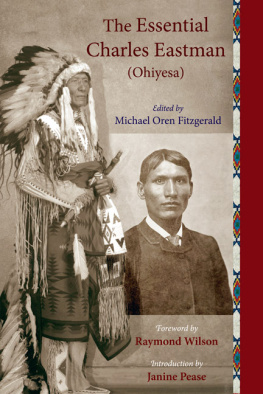

Charles Eastman (Dakota name Ohiye Sa) was born on aSantee Sioux Reservation in Minnesota in 1858, the son of afull-blood father named Tawakanhdeota (Many Lightnings) and ahalf-Dakota mother named Winona. His mother died shortly after hisbirth, and he was given the birth-name Hakadah (The Sad LastOne).

In 1862, there was an uprising on the Reservation,and in the chaos Hakadah was separated from his father and taken torelatives in North Dakota and neighboring Canada. Here his uncleand grandmother, fearing that Many Lightnings had been killed,raised the boy in the traditions of the Dakota, giving him the newname Ohiye Sa (Wins Often). Brought up as a hunter and a warrioruntil he was 15, Ohiye Sa was about to return to Minnesota to, inthe Dakota tradition, avenge the death of his father, when he wassurprised to learn that his father had survived the Sioux Uprising,had given up the Dakota ways, learned English, and was now a farmerand rancher, having taken the Christian name Jacob Eastman.

Ohiye Sa returned with his father and his olderbrother to their homestead in the Dakota Territory. There, he cuthis long hair, took the Christian name Charles Eastman, and beganattending the local government-run Indian school.

Young Charles showed academic promise at the localmission school and, encouraged by his father, continued at anotherIndian school in Nebraska. With the aid of some missionaries,Eastman went on to attend Dartmouth College, where he graduated in1887, then went on to medical school at Boston University.

After obtaining his medical degree, Eastman went towork for the Indian Health Service, serving as an agency doctor atthe Pine Ridge and Crow Creek Reservations in South Dakota. In1890, after the massacre at Wounded Knee, Eastman was on the sceneand treated many of the wounded Dakota women and children.

Like his father, Eastman came to believe that theonly way the Dakota people could survive was to adopt American waysand integrate into white society. After the Wounded Knee massacre,he began working to establish YMCA chapters on variousreservations, and encouraged Dakota children to go to Indianschools like the one in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where NativeAmerican children were stripped of their traditional culture andlanguage, and taught to live like white people. During his workwith the Indian Agency, Eastman came to know virtually every memberof the tribe personally.

Eastmans work with young children at the YMCA caughtthe attention of the American naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton, andDaniel Carter Beard, director of a boys club called The Sons ofDaniel Boone. Together, the three founded the Boy Scouts ofAmerica in 1910.

For several years, Eastman worked as the officialrepresentative in Washington DC for the Sioux nation. He then wenton to become an advisor on Indian affairs to Presidents TeddyRoosevelt and Calvin Coolidge.

Eastman also believed, however, that the Dakotashould keep their traditional tribal identities. Beginning in 1902,Eastman, fearing that the traditional ways would be lost, took upwriting as a way of making Dakota culture and traditions morewidely known and appreciated. His first book, Indian Boyhood, wasan autobiography of his early life with the free Dakota in Canada,published in 1902. Ten other books followed. Sioux FolktalesRetold, a collection of traditional Dakota myths and stories, waspublished in 1909, under the title Wigwam Evenings. The Soul of theIndian, a description of Dakota religious beliefs and ceremonies,was published in 1911. His last book, Indian Heroes and GreatChieftains, was a collection of short biographical sketches ofprominent Native American leaders (many of whom Eastman knewpersonally). It was published in 1918.

Eastman died in January 1939.

Indian Boyhood

Part I - Earliest Recollections

Hadakah, The Pitiful Last

What boy would not be an Indian for a while when hethinks of the freest life in the world? This life was mine. Everyday there was a real hunt. There was real game. Occasionally therewas a medicine dance away off in the woods where no one coulddisturb us, in which the boys impersonated their elders, BraveBull, Standing Elk, High Hawk, Medicine Bear, and the rest. Theypainted and imitated their fathers and grandfathers to the minutestdetail, and accurately too, because they had seen the real thingall their lives.

We were not only good mimics but we were closestudents of nature. We studied the habits of animals just as youstudy your books. We watched the men of our people and representedthem in our play; then learned to emulate them in our lives.

No people have a better use of their five senses thanthe children of the wilderness. We could smell as well as hear andsee. We could feel and taste as well as we could see and hear.Nowhere has the memory been more fully developed than in the wildlife, and I can still see wherein I owe much to my earlytraining.

Of course I myself do not remember when I first sawthe day, but my brothers have often recalled the event with muchmirth; for it was a custom of the Sioux that when a boy was bornhis brother must plunge into the water, or roll in the snow nakedif it was winter time; and if he was not big enough to do either ofthese himself, water was thrown on him. If the new-born had asister, she must be immersed. The idea was that a warrior had cometo camp, and the other children must display some act ofhardihood.

I was so unfortunate as to be the youngest of fivechildren who, soon after I was born, were left motherless. I had tobear the humiliating name Hakadah, meaning the pitiful last,until I should earn a more dignified and appropriate name. I wasregarded as little more than a plaything by the rest of thechildren.

My mother, who was known as the handsomest woman ofall the Spirit Lake and Leaf Dweller Sioux, was dangerously ill,and one of the medicine men who attended her said: Anothermedicine man has come into existence, but the mother must die.Therefore let him bear the name Mysterious Medicine. But one ofthe bystanders hastily interfered, saying that an uncle of thechild already bore that name, so, for the time, I was onlyHakadah.

My beautiful mother, sometimes called theDemi-Goddess of the Sioux, who tradition says had every featureof a Caucasian descent with the exception of her luxuriant blackhair and deep black eyes, held me tightly to her bosom upon herdeath-bed, while she whispered a few words to her mother-in-law.She said: I give you this boy for your own. I cannot trust my ownmother with him; she will neglect him and he will surely die.

The woman to whom these words were spoken was belowthe average in stature, remarkably active for her age (she was thenfully sixty), and possessed of as much goodness as intelligence. Mymothers judgment concerning her own mother was well founded, forsoon after her death that old lady appeared, and declared thatHakadah was too young to live without a mother. She offered to keepme until I died, and then she would put me in my mothers grave. Ofcourse my other grandmother denounced the suggestion as a verywicked one, and refused to give me up.