THE SOUL OF THE INDIAN

AN INTERPRETATION

* * *

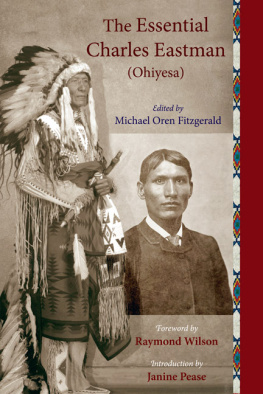

CHARLES A. EASTMAN

*

The Soul of the Indian

An Interpretation

From a 1911 edition

ISBN 978-1-62011-437-7

Duke Classics

2012 Duke Classics and its licensors. All rights reserved.

While every effort has been used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information contained in this edition, Duke Classics does not assume liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions in this book. Duke Classics does not accept responsibility for loss suffered as a result of reliance upon the accuracy or currency of information contained in this book.

Contents

*

*

TO MY WIFEELAINE GOODALE EASTMANIN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION OF HEREVER-INSPIRING COMPANIONSHIPIN THOUGHT AND WORKAND IN LOVE OF HER MOSTINDIAN-LIKE VIRTUESI DEDICATE THIS BOOK

I speak for each no-tongued tree

That, spring by spring, doth nobler be,

And dumbly and most wistfully

His mighty prayerful arms outspreads,

And his big blessing downward sheds.

SIDNEY LANIER.

But there's a dome of nobler span,

A temple given

Thy faith, that bigots dare not ban

Its space is heaven!

It's roof star-pictured Nature's ceiling,

Where, trancing the rapt spirit's feeling,

And God Himself to man revealing,

Th' harmonious spheres

Make music, though unheard their pealing

By mortal ears!

THOMAS CAMPBELL.

God! sing ye meadow streams with gladsome voice!

Ye pine-groves, with your soft and soul-like sounds!

Ye eagles, playmates of the mountain storm!

Ye lightnings, the dread arrows of the clouds!

Ye signs and wonders of the elements,

Utter forth God, and fill the hills with praise!...

Earth, with her thousand voices, praises GOD!

COLERIDGE.

Foreword

*

"We also have a religion which was given to our forefathers,and has been handed down to us their children. It teaches us to bethankful, to be united, and to love one another! We never quarrelabout religion."

Thus spoke the great Seneca orator, Red Jacket, in his superbreply to Missionary Cram more than a century ago, and I have oftenheard the same thought expressed by my countrymen.

I have attempted to paint the religious life of the typicalAmerican Indian as it was before he knew the white man. Ihave long wished to do this, because I cannot find that it has everbeen seriously, adequately, and sincerely done. The religion ofthe Indian is the last thing about him that the man of another racewill ever understand.

First, the Indian does not speak of these deep matters so longas he believes in them, and when he has ceased to believe he speaksinaccurately and slightingly.

Second, even if he can be induced to speak, the racial andreligious prejudice of the other stands in the way of hissympathetic comprehension.

Third, practically all existing studies on this subjecthave been made during the transition period, when the originalbeliefs and philosophy of the native American were alreadyundergoing rapid disintegration.

There are to be found here and there superficial accounts ofstrange customs and ceremonies, of which the symbolism or innermeaning was largely hidden from the observer; and there has been agreat deal of material collected in recent years which is withoutvalue because it is modern and hybrid, inextricably mixed withBiblical legend and Caucasian philosophy. Some of it has even beeninvented for commercial purposes. Give a reservation Indiana present, and he will possibly provide you with sacred songs, amythology, and folk-lore to order!

My little book does not pretend to be a scientific treatise.It is as true as I can make it to my childhood teaching andancestral ideals, but from the human, not the ethnologicalstandpoint. I have not cared to pile up more dry bones, but toclothe them with flesh and blood. So much as has been written bystrangers of our ancient faith and worship treats it chiefly asmatter of curiosity. I should like to emphasize its universalquality, its personal appeal!

The first missionaries, good men imbued with the narrowness oftheir age, branded us as pagans and devil-worshipers, and demandedof us that we abjure our false gods before bowing the knee at theirsacred altar. They even told us that we were eternally lost,unless we adopted a tangible symbol and professed a particular formof their hydra-headed faith.

We of the twentieth century know better! We know that allreligious aspiration, all sincere worship, can have but one sourceand one goal. We know that the God of the lettered and theunlettered, of the Greek and the barbarian, is after all the sameGod; and, like Peter, we perceive that He is no respecterof persons, but that in every nation he that feareth Him andworketh righteousness is acceptable to Him.

CHARLES A. EASTMAN (OHIYESA)

I - The Great Mystery

*

Solitary Worship. The Savage Philosopher. The Dual Mind.Spiritual Gifts versus Material Progress. The Paradox of"Christian Civilization."

The original attitude of the American Indian toward the Eternal,the "Great Mystery" that surrounds and embraces us, was as simpleas it was exalted. To him it was the supreme conception, bringingwith it the fullest measure of joy and satisfaction possible inthis life.

The worship of the "Great Mystery" was silent, solitary, freefrom all self-seeking. It was silent, because all speech is ofnecessity feeble and imperfect; therefore the souls of my ancestorsascended to God in wordless adoration. It was solitary, becausethey believed that He is nearer to us in solitude, and there wereno priests authorized to come between a man and his Maker. Nonemight exhort or confess or in any way meddle with the religiousexperience of another. Among us all men were created sons of Godand stood erect, as conscious of their divinity. Our faith mightnot be formulated in creeds, nor forced upon any who wereunwilling to receive it; hence there was no preaching, proselyting,nor persecution, neither were there any scoffers or atheists.

There were no temples or shrines among us save those ofnature. Being a natural man, the Indian was intensely poetical.He would deem it sacrilege to build a house for Him who may be metface to face in the mysterious, shadowy aisles of the primevalforest, or on the sunlit bosom of virgin prairies, upon dizzyspires and pinnacles of naked rock, and yonder in the jeweled vaultof the night sky! He who enrobes Himself in filmy veils of cloud,there on the rim of the visible world where ourGreat-Grandfather Sun kindles his evening camp-fire, He who ridesupon the rigorous wind of the north, or breathes forth His spiritupon aromatic southern airs, whose war-canoe is launched uponmajestic rivers and inland seasHe needs no lesser cathedral!

That solitary communion with the Unseen which was the highestexpression of our religious life is partly described in the wordbambeday, literally "mysterious feeling," which has beenvariously translated "fasting" and "dreaming." It may better beinterpreted as "consciousness of the divine."

The first bambeday, or religious retreat, markedan epoch in the life of the youth, which may be compared to that ofconfirmation or conversion in Christian experience. Having firstprepared himself by means of the purifying vapor-bath, and cast offas far as possible all human or fleshly influences, the young mansought out the noblest height, the most commanding summit in allthe surrounding region. Knowing that God sets no value uponmaterial things, he took with him no offerings or sacrifices otherthan symbolic objects, such as paints and tobacco. Wishing toappear before Him in all humility, he wore no clothing save hismoccasins and breech-clout. At the solemn hour of sunrise orsunset he took up his position, overlooking the glories of earthand facing the "Great Mystery," and there he remained, naked,erect, silent, and motionless, exposed to the elements and forcesof His arming, for a night and a day to two days and nights, butrarely longer. Sometimes he would chant a hymn without words, oroffer the ceremonial "filled pipe." In this holy trance or ecstasythe Indian mystic found his highest happiness and the motive powerof his existence.