All rights reserved.

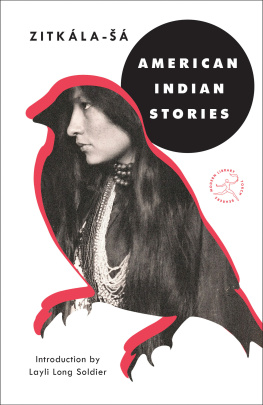

Published in the United States by Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Modern Library and the Torchbearer colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

INTRODUCTION

LAYLI LONG SOLDIER

Entering Zitkla-s work is a piercing experience. She was born into, educated by, and lived through some of the most dramaticone would say genocidalchanges for our people. At times while reading I have to swallow, stop, and close the book. I must let her work rest, let my body rest, and enter again slowly. As a Lakota and as a woman, I feel a personal connection and literary lineage to Zitkla-. Likewise, we share tribal kinship through the Oeti akowin, so her writing often stirs in me an unexplainable vulnerability and empathy. Yet to the thoughtful reader of any heritage her work offers testament to the power of language, documentation, resistance, and maintaining a tenacious hold on cultural values.

To feel deeply the import of Zitkla-s writing, one should engage in a spectral reading, a movement through and fluid flipping back and forth from her short stories and poems to her nonfiction. Doing this, we get a sense, a fragrance, of her spirit. By spirit is meant her intent. Her drive and motivations. In The School Days of an Indian Girl, Zitkla-s autobiographical account of her boarding school experience, she writes, I ventured upon a college career against my mothers will. I had written for her approval, but in her reply I found no encouragement.Her few words hinted that I had better give up my slow attempt to learn the white mans ways, and be content to roam over the prairies and find my living upon wild roots. I silenced her by deliberate disobedience. From this we can cross-thread a kind of discourse into The Soft-Hearted Sioux. As the protagonist, a young Sioux man converted to Christianity through mission school, sits at an open fire with his parents, his grandmother fills her stone pipe and asks, My grandchild, when are you going to bring here a handsome young woman? His response is that tense and familiar thread of silence: I stared into the fire rather than meet her gaze.I said nothing in reply. And to his fathers urging that he assume his role as a warrior, the soft-hearted Sioux admits, Not a word had I to give in answer. Its here that we sense the primary and most ruinous conflict of Zitkla-s time: the unsettling inside the homes, families, and communities of Native people. The most gruesome conflict, make no mistake, was within the self, in the individual heart that was, at one time, culturally defined by connection to others. Native people of Zitkla-s era had to dig, search, and come to terms with what they were capable of, which was sometimes unspeakable. What would we say to one another, in our familieswhat words would ever surface from our throatsto explain the choices Zitkla-s generation had to make? We may wish to consider that in moments of rupture and devastation (e.g., earthquake, volcanic eruption, heartbreak, settler invasion) there are often no words, only the sudden and unimaginable upheaval. Then a violent tearing and breaking. Then silence. All is still. This silence hangs in the air, in the body, until the senses snap alive. And we find ourselves spinning around, frantically, to survey what remains. Its an echo of what the soft-hearted Sioux cried: The moon and stars began to move. Now the white prairie was sky, and the stars lay under my feet. Now again they were turning. At last the starry blue rose up into place. The noise in my ears was still. A great quiet filled the air. In my hand I found my long knife dripping with blood.

We ponder the essential grit and wound of Zitkla-s time to understand that her writing was never a fanciful, privileged exploration of an imagined Other. Rather, her work was a coal bed, searing with embers of experience, and has become documentation for future generations of the fires she walked through. In her own breakingnamely, her separation from Dakota homelife into boarding schoolZitkla- explains that the melancholy of those black days has left so long a shadow that it darkens the path of years that have since gone by. We think about this wound not to permanently fix her work in grief, but to understand that it was essential to her writing, her activism, and her lifes purpose. She took up the physical pen and paper, the objects of the white mans ways, and embraced the very education that came from those black days. Yet hers was not a nave and grinning acceptance of these tools. In accounts of her childhood, we know that Zitkla- displayed a prodigious sense of how and when to enact subversion and revenge. Tormented by Christian doctrine that seeped into dreams about the devil, for example, she took a pencil from her apron pocket one morning and pulled a copy of The Stories of the Bible down from a shelf. In her words, I began by scratching out his wicked eyes. A few moments laterthere was a ragged hole in the page where the picture of the devil had once been. Here we see subversion. As in, who would find the ragged hole? Or when would this page be discovered? And who knows if the book, tucked into a shelf, would ever be opened to that page again anyway? But more important, she responded to the dream. She excised its power over her by taking action. Zitkla- herself names this as revenge. While some may reject or shy away from notions of revenge, we must also remember that when enacted with a certain poetic sensibility and strength, revenge can be a teacher. For us, Zitkla- has dug a hole into the page. She has scratched the eyes out of the devil. When we hold her page, thus, a light streams through.

Lets also consider the tone and language that Zitkla- employed. In her approach there is, at times, a gentleness and a conscious, nonthreatening invitation to the non-Native reader that could alternately be interpreted as appeasing, submissive kowtowing, or, worse, a diminishment of the importance of her truth-telling. In The Great Spirit, for example, she muses about her walks in the green hills along the Missouri River, immersed in the natural beauty of Creation itself. She writes with wonder, gazing with a childs eager eye. Here the perspective is deeply reflective, intimately told through the personal I. However, as she recounts a traditional Dakota story about Stone-Boy, she shifts into the explanatory mode, clearly narrating for non-Native readers. Her word choice could be viewed as teetering toward othering the Native perspective, in moments such as Here the Stone-Boy, of whom the American aborigine tells Or with the thread of this Indian legend of the rock, I fain would trace a subtle knowledge of the native folk And so on. In contemporary conversations, this approach may be viewed as unnecessary, or perhaps, in the most severe discussions, as a kind of pandering. As in, why explain? Why not just say the say?

Yet, given Zitkla-s background, I am prone to credit her with an exacting intelligence. Im inclined to think that she knew precisely what she was doing and the effect of each word; that she wielded her tools purposefully; and that her driving intent was not to appease but, consistent with her larger body of work, to make a statement aimed directly at the forehead of colonialism.