2015 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Composed in Charter, a typeface designed by Matthew Carter

18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-295-99477-2

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ISBN-13: 978-0-295-80605-1 (electronic)

For Kristin, Melody, and Kerysas is everything

There is no one who has been a close observer of Indian history who is not well satisfied that one of the two things must eventually take place, to wit, either civilization or extinction.

Commissioner of Indian Affairs Hiram Price, 1881

To uproot a child from his natural environment without making any effort to teach him how to adjust himself to a new environment, and then send him back to the old, especially with a people at a stage of civilization where the influence of family and home would normally be all-controlling, is to invite disaster.

Meriam Report, 1928

Foreword

Theodore Jojola

When the Albuquerque Indian School (AIS) was founded in 1881, Albuquerque was literally a one-horse town. New Mexico was still an American territory. The last US campaign against the Comanches occurred in 1874, and the railroad finally reached town in 1880. In that year, Albuquerques population was estimated to be only 2,315, and New Town (now downtown Albuquerque) only existed on a blueprint.

The denizens of Albuquerque saw economic opportunity in an Indian school. They seeded the campus with sixty-six acres of swamp grassland, bought for a paltry $4,300. That investment grew manifold. By 1892, the school already had a sprawling campus, with forty-four acres under cultivation and an enrollment of 314. By comparison, the University of New Mexico (UNM) had been founded in 1889 with just one building and seventy-five students.

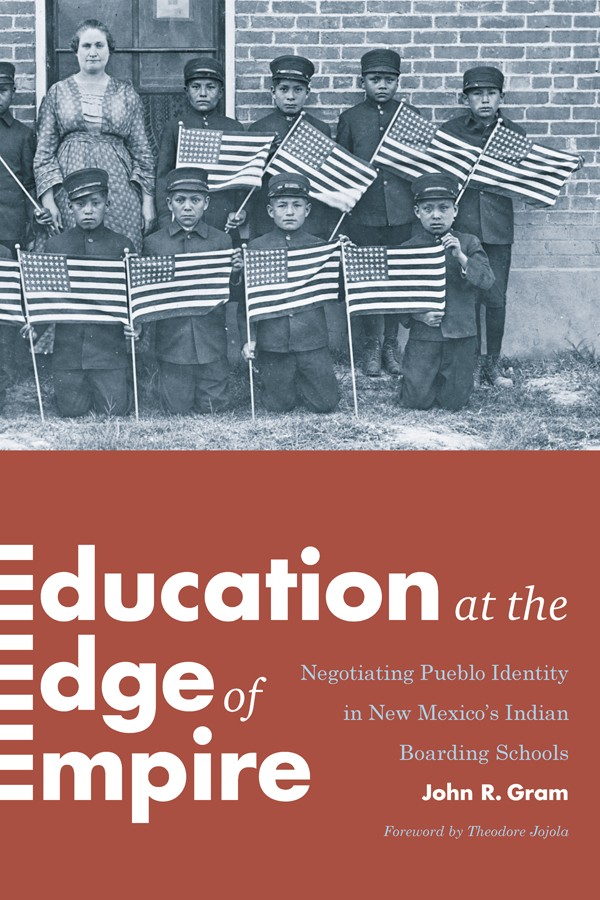

Originally opened by the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions, AIS transferred to US government control in 1886. Education was met through religious and military indoctrination by a system exemplified at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Children from the surrounding region, largely Pueblo, Navajo and Apache, were uprooted from their communities and detained at the school.

From the beginning, the school was beset by ideological challenges. In 1892, a writ of habeas corpus by the itinerant journalist Charles Fletcher Lummis was filed on behalf of his Isleta Pueblo landlord. It accused the schools superintendent, William B. Creager, of instigating a Presbyterian plan to kidnap and detain children against their will. By then, Pueblo parents had already begun withholding their children at the urging of Roman Catholic parish priests. Under the weight of declining enrollment, the superintendent relented, and the school became less a one-way agent of white assimilation and more open and community oriented. Over the long term, the shift facilitated the cultural cross-assimilation of both students and faculty alike. Native students aspired to be like their mentors, and the teachers opened themselves up to the Indian culture. Nowhere in the litany of Indian boarding schools did this appear to happen.

At the school, boys were educated in the industrial trades, while the girls had to settle for the domestic arts. These vocations provided for much of the schools own needs. The students grew much of their own food, tailored and fashioned their own clothing, and even provided the labor for school construction and upkeep. The schools outing program farmed out the Indian children to responsible white people. to work as housekeepers and helpers.

By the turn of the century, the campus became the civilized hub of New Town, where residents took part in social events and galas. Native children were lauded for their intelligence, and their school projects were showcased in venues far and wide. Items such as pottery, art, jewelry, and weaving were regularly exhibited at local fairs; in 1904, students pottery was even showcased at the Worlds Fair in Saint Louis.

When New Mexico gained statehood in 1912, AIS had a kindergarten, a primary school, and eight regular grades. It boasted that its students had made 1,500 pairs of shoes and baked 140,000 loaves of bread. Its scholastics were said to integrate good health, Christian values, learning a trade, and the love of music and good books.

By the time US Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier ended the military system for all Indian boarding schools in 1932, AIS had already added an eleventh and twelfth grades. The campus consisted of forty-eight buildings, and in 1931, 927 students were enrolled, 304 of them in high school.

Regimental education was abolished, and the curriculum was expanded to include a Native Arts and Crafts department. Boys were instructed in silversmithing. Two native women who did weaving and embroidery were hired as full-time instructors to teach the girls. The departments fame in these crafts became equal to the Dorothy Dunn Indian Art Studio at the Santa Fe Indian School.

As the students continued to excel in their basic studies, those with the highest academic potential were singled out for a downtown student exchange program. In order to prove to the rest of the region that Indian children were equal in intelligence to other children, they were placed at local Catholic and public schools. In time, a UNM Lodge was created at AIS to board Indian students.

Although the school physically divided the sexes and controlled their social interactions, many intertribal marriages occurred among its graduates. When it came to serving during wartime, both the schools young men and young women volunteered. They willingly fought and died in World War I, World War II, and other wars. Many of the famed Navajo Code Talkers were graduates of AIS. This all went by way of saying that the school prepared students to assume their rightful roles as dual citizens, both inside and outside their traditional communities.

Despite the schools accomplishments, the ill winds of Indian policy change eventually weakened its foundation. Beginning with the Termination Policy of the 1950s, the school gradually became estranged from the Indian community. The Johnson OMalley (JOM) program took Indian children out of the boarding system and placed them in the public school system. In the 1960s, the Navajo Nation used JOM funds to establish a bordertown program at AIS. Although Navajo children continued to be housed there, they went to public school. The campus essentially became divided.

In the 1970s, tribal people became increasingly disillusioned by the inadequacy of the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) system. Moreover, the Red Power movement emboldened them to rally against it. This affected the quality of education at AIS, especially after funds to support instruction and programs were cut. In 1975, the BIA reported that 75 percent of the schools student body had been expelled from other schools and that AIS had been singled out as the worst of the worst. In 1977, the All Indian Pueblo Council (AIPC) used the provisions of the Indian Self Determination and Education Assistance Act to take over the management of the school. By the next year, however, enrollment had declined to 156 and the majority of the schools buildings were in disrepair or vacant.