C HANGED F OREVER

Volume 1

SUNY series, Native Traces

Jace Weaver and Scott Richard Lyons, editors

Changed Forever

Volume I

A MERICAN I NDIAN

B OARDING -S CHOOL L ITERATURE

Arnold Krupat

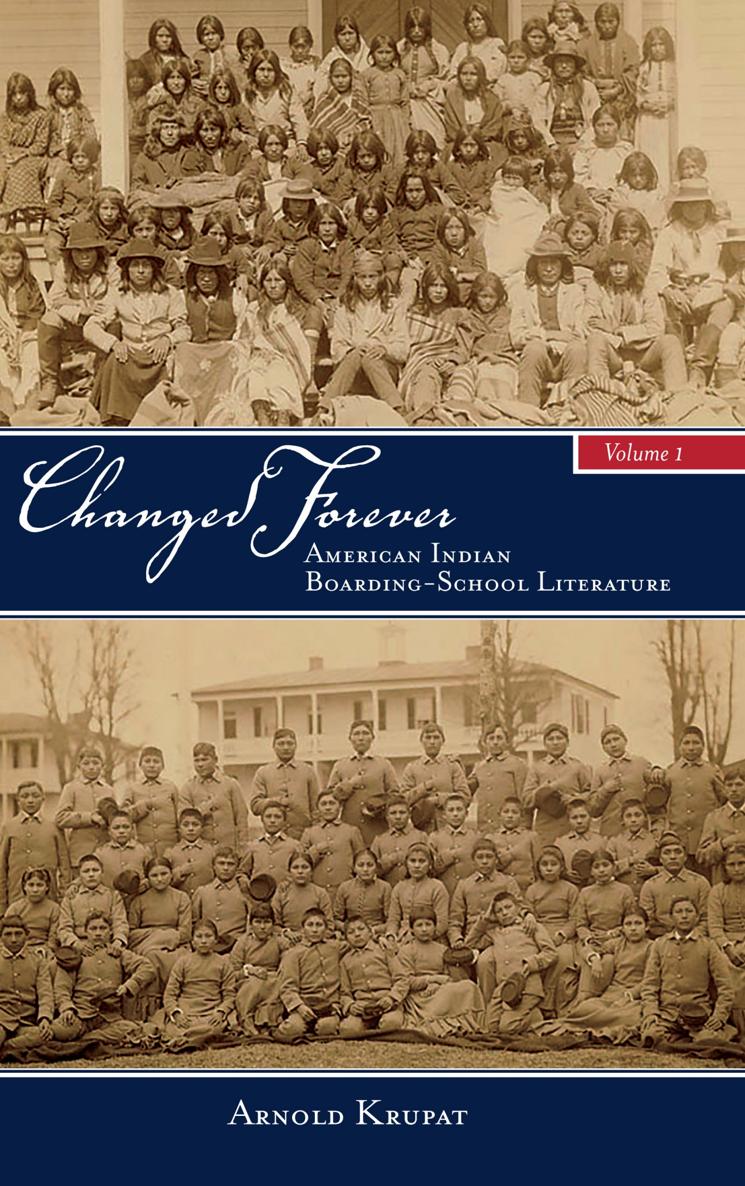

On the cover: Apache students on their arrival at Carlisle Indian School in 1886 and three years after, both photographs taken by John N. Choate. Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Krupat, Arnold, author.

Title: Changed forever : American Indian boarding school literature. Volume I / Arnold Krupat. Other titles: American Indian boarding school literature

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York Press, [2018] | Series: SUNY series, Native traces | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017022009 (print) | LCCN 2018005523 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438469164 (e-book) | ISBN 9781438469157 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Off-reservation boarding schoolsUnited StatesBiography. | Boarding school studentsUnited StatesBiography. | Indian studentsUnited StatesBiography. | Hopi IndiansBiography. | Navajo IndiansBiography. | Apache IndiansBiography. | AutobiographiesIndian authors.

Classification: LCC E97.5 (ebook) | LCC E97.5.K78 2018 (print) | DDC 371.829/97dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Julian Rice

What has become of the thousands of Indian voices who spoke the breath of boarding-school life?

K. Tsianina Lomawaima

We still know relatively little about how Indian school children themselves saw things.

Michael Coleman

Boarding-school narratives have a significant place in the American Indian literary tradition.

Amelia Katanski

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MANY PEOPLE HAVE ENCOURAGED AND HELPED ME THROUGHOUT MY WORK on this book, and it is a pleasure to thank them. Professors Scott Lyons and Jace Weaver, editors of the Native Traces Series at the SUNY Press, supported this project from its earliest stages and offered useful suggestions until the latest stages, and I thank them both. Scott invited me to participate in two seminars at the University of Michigan for which I am grateful, and my gratitude extends to his students and colleagues for their responses. Dr. Peter Whiteley of the American Museum of Natural History read early drafts of a couple of the Hopi sections of this book, corrected many errors large and small, and generously offered the benefits of his enormous erudition on all things Hopi. Occasional email exchanges with Professor Paul John Eakin and Dr. Julian Rice were consistently illuminating and encouraging, and I thank both of them. Geoff Danisher of the Sarah Lawrence College Library obtained a great many interlibrary-loan materials for me. I would, in this as in former projects, have been lost without his help. Mika Kennedy of the University of Michigan provided valuable information regarding illustrations, and Jean Hofheimer Bennett enhanced my meager computer skills. Two anonymous readers for the SUNY Press offered useful suggestions for revision for which I am grateful, and I am grateful, too, for the work of my editor, Amanda Lanne-Camilli. An earlier version of the study of Edmund Nequatewas Born a Chief appeared in the journal, a/b:autobiography studies , and I thank the editors for permission to reprint.

INTRODUCTION

FROM THE FIRST MOMENTS THEY SET FOOT ON THESE SHORES, THE European invader-settlers of America confronted an Indian problem. This consisted of the simple fact that Indians occupied lands the newcomers wanted for themselves. To be sure, this was not the case for the Spanish invaders of the Southeast and Southwest in the mid-sixteenth century, whose intent for the most part was to find treasure and to convert and missionize the tribal peoples they encountered. But in the Northeast, the English, from the early seventeenth century, and then the Americans, as they made their way across the continent, came to understand that, broadly speaking, Americas Indian problem permitted of only two solutions, extermination or education. Extermination was costly, sometimes dangerous, and, too, it also seemed increasingly wrong .

In time, it began to appear wiser, as the title of Robert Trennerts Introduction to a study of the Phoenix Indian School put the matter, for policymakers to proceed according to the assumption that The Sword Will Give Way to the Spelling Book (1988, 3), thus offering, again to cite Trennert, an Alternative to Extinction (1975). Educating Native peoplesteaching them to speak, read, and write English, to convert to one or another version of Christianity, and to accept an individualism destructive of communal tribalism, ethnocide rather than genocidewas a strategy that might more efficiently free up Native landholdings and transform the American Indian into an Indian-American, inhabiting, if not quite melted into, the broad pot of the American mainstream.

In a fine 1969 study, Brewton Berry remarked that so far as the choice between coercion and persuasion (23) was concerned, Formal education has been regarded as the most effective means of bringing about assimilation (22). Robert Trennert writes that when the Phoenix Indian School was founded in 1891, it was for the specific purpose of preparing Native American children for assimilation. to remove Indian youngsters from their traditional environment, obliterate their cultural heritage, and replace that with the values of white middle-class America. Complicating the matter, he adds, was the fact that the definition of assimilation was repeatedly revised between 1890 and 1930 (1988, xi). Further complicating the matter well into the 1960s was the fact that white middle-class America was generally not willing to accommodate persons of color regardless of whether they shared its values or not.

In the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1890, the Rules for Indian Schools stated clearly that the government, in organizing this system of schools, intended for them to be preparatory and temporary; that eventually they will become unnecessary, and a full and free entrance be obtained for Indians into the public school system of the country. It is to this end, the Rules continued, that all officers and employees of the Indian school service should work (in Bremner, vol. ii, 1,354). Although a full and free entrance to all public schools in the United States was legally available to Native Americansas it was not to African Americanson those occasions when they availed themselves of the right to attend, they were not especially welcomed or well served. Indeed, as Wilbert Ahern has written, The local public schools to which 53% of Indian children went in 1925, were even less responsive to Indian communities than the BIA schools (1996, 88).