Contents

Guide

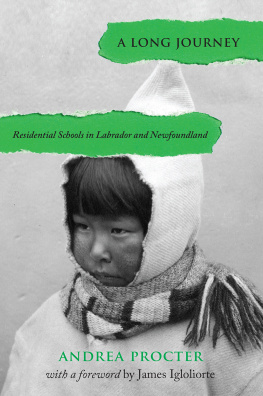

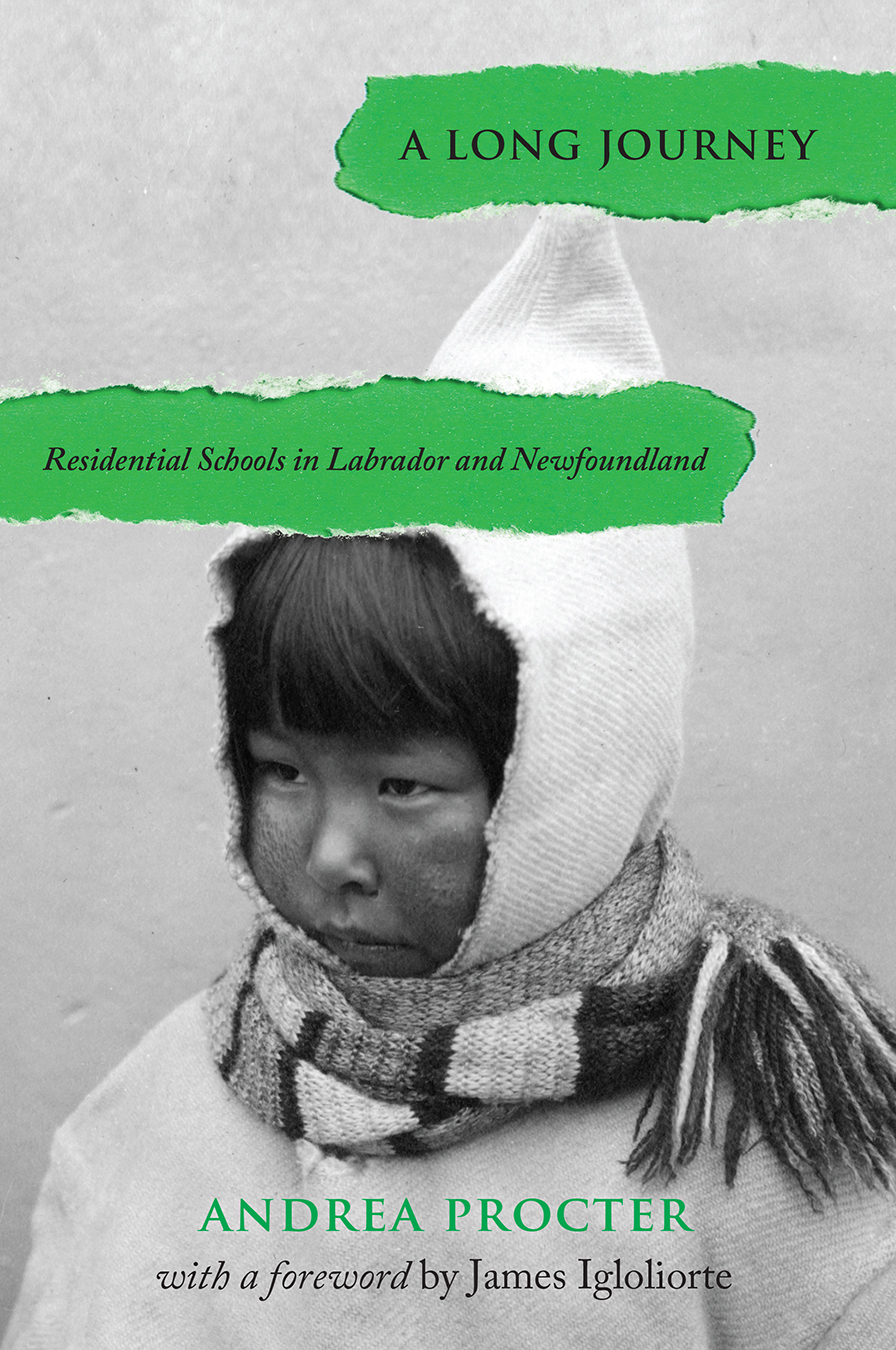

A LONG JOURNEY

A LONG JOURNEY

Residential Schools in Labrador and Newfoundland

Andrea Procter

2020 Andrea Procter

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: A long journey : residential schools in Labrador and Newfoundland / Andrea Procter.

Names: Procter, Andrea H., 1974- author.

Series: Social and economic studies (St. Johns, N.L.); no. 86.

Description: Series statement: Social and economic studies; no. 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20200168398 | Canadiana (ebook) 20200168436 | ISBN 9781894725644 (softcover) | ISBN 9781894725668 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781894725675 (Kindle) | ISBN 9781894725651 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Boarding schoolsNewfoundland and LabradorHistory. | CSH: Native peoplesResidential schoolsNewfoundland and LabradorHistory. | CSH: Native studentsNewfoundland and LabradorHistory.

Classification: LCC E96.5 .P76 2020 | DDC 371.829/970718dc23

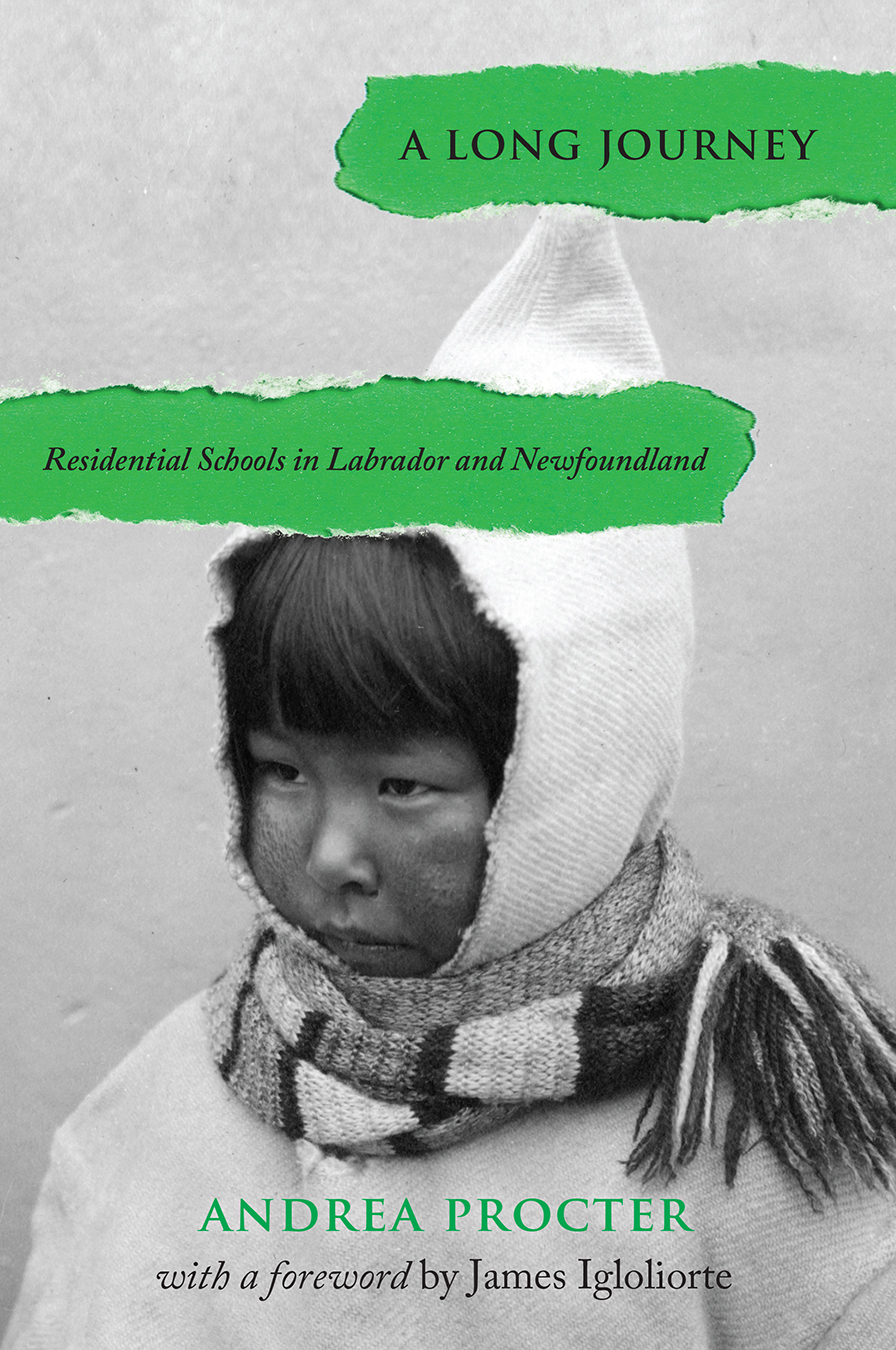

Cover image: Lizzie Lucy at the St. Anthony orphanage, ca.1932 (courtesy of The Rooms)

Cover design: Alison Carr

Page design and typesetting: Alison Carr

Copy editing: Richard Tallman

Published by ISER Books

Institute of Social and Economic Research

Memorial University of Newfoundland

PO Box 4200

St. Johns, NL A1C 5S7

www.hss.mun.ca/iserbooks/

Printed in Canada

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

S erendipity, or happy coincidence, played a large part in Andrea Procter coming to write this scholarly work on education in Labrador. After several unsuccessful attempts to engage prominent writers who were known to the Indigenous community in Labrador, my friend Dr. Hans Rollmann gave me Andreas name as someone who was knowledgeable in Labradors Indigenous culture and who had a track record of a good working relationship within the community. As each of the potential candidates presented good reasons why scheduling, personal circumstances, and geography among other things would not allow them to complete this work, our good fortune found Andrea at a stage of her academic and working career to enthusiastically accept the concept of the Healing and Commemoration process we laid out to her.

As the lengthy class action lawsuit that had proceeded through the Newfoundland and Labrador Supreme Court came to an abrupt close with the proactive actions of the Trudeau Liberals in 2016, the western Canadian law firm of Ahlstrom Wright Oliver and Cooper LLP, led by the ebullient Steven Cooper and represented in this province by the firm run by John Crosbie, Q.C. acting on behalf of the plaintiff students, reached a negotiated Settlement Agreement with Canada alone; the other defendants the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, The International Grenfell Association, and the Moravian Church were all absolved of liability through the settlement process. No doubt these parties breathed a sigh of relief from the lifting of the potential for financial burden or a negative impact on their corporate image. For the students, this simply meant some additional worry as the opportunity to hear acknowledgement and apologies from Newfoundland, the IGA, and the Moravian Church hierarchy was swept away by the stroke of a pen.

Canada and Cooper proceeded in a Settlement Agreement process to ask the Indigenous leaders of the Inuit, NunatuKavut people, and Innu Nation to select representatives as the preliminary step in a consultation process to breathe life into the Agreement. From there, the law firm selected plaintiff Toby Obed; the Innu Nation chose Helen Andrew; NunatuKavut Community Council selected Kirk Lethbridge; and the Nunatsiavut government chose me. We held a preliminary meeting in Ottawa in June 2017, and among other decisions made then, I was appointed as Ministerial Special Representative to partner with federal government colleagues in a project of Healing and Commemoration activities to honour the group of some 950 students.

Our small advisory panel listened to the lawyers and federal government officials, who presented a list of potential ideas to discuss and make additional comments upon, and while the Healing and Commemoration Advisory Panel, as we were called, generally liked the negotiated agreements mentioned, we, as Indigenous people, balked at being the voice for all the students without further consultation with the larger student group back home. We thought a further meeting in a Labrador location with a sample of students might give everyone a better chance to hear a clearer, expanded, and inclusive list of reconciliation activities.

The next meeting did indeed have strong support for a priority list of activities: a personal visit to Labrador by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau with a formal apology to representative students and Indigenous officials; artists and craftspersons contracted to produce lasting and meaningful pieces for everyone to celebrate; community visits to hear students personal experiences in the schools; a permanent sound and visual record of digitally produced vignettes; and, finally and importantly, a recounting of the history of education in Labrador with an emphasis on how the delivery of education evolved to become our piece of the Canadian jigsaw puzzle of federal and provincial policies, imposed on the Indigenous population, that served to demonstrate the colonial influences so representative of an era that perpetuated insidious bigotry and a dismissive attitude of any cultural norms not held as Christian or Eurocentric.

Thus began a year and a half journey to work towards the goal of commemoration of the resilience of the students, and to employ the healing benefits of talking within a respectful, safe, comforting setting with trained professionals who were willing to act as mentors, supports, sounding boards, confidants, and, in many cases, friends to anyone who wanted to speak about any aspect of school life, personal mental growth, challenges, aspirations, and reflections. The interventions, we were told in these sessions, allowed many to find a sense of lightheartedness or of a load being lifted from ones shoulders as they recounted their experiences. Finally, someone was listening to their personal stories of childhood pain, shame, and loss, tempered with growth and resilience as they reflected on these times as adults.

Andrea Procter agreed to join us in these sessions. She knew many students intimately, and her understanding of the histories of the communities in the context of schooling made everyone appreciate her presence. She joins an impressive group of scholars and historians who are expanding our knowledge of the Indigenous peoples of Labrador and their relationships with the provincial and federal governments and their numerous agents of assimilating forces. Following in the footsteps of Carol Brice-Bennett in Our Footprints Are Everywhere, Maura Hanrahan in The Lasting Breach: The Omission of Aboriginal People from the Terms of Union between Newfoundland and Canada and Its Ongoing Impacts, and Martha MacDonald in Inside Stories: Agency and Identity through Language Loss Narratives in Nunatsiavut, and others, Dr. Procter has gathered a fascinating account of the recorded annals, books, archives, and personal stories to provide an up-to-date and comprehensive appreciation of the Labrador experience. She chronicles how the experiences of Indigenous children in Labrador shifted from a family-centred, culturally relevant immersion in life to the worldwide phenomenon of Christian-based norms and values that combined with subtle and overt colonialist attitudes to drive a wedge between these children and their families and distinctive culture.