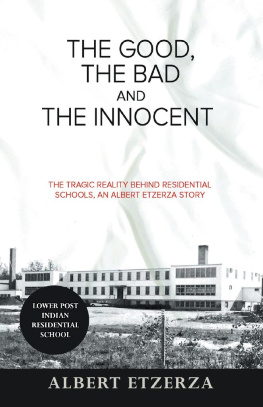

The Good, the Bad and the Innocent

The Tragic Reality Behind Residential Schools, an Albert Etzerza Story

Albert Etzerza

The Good, the Bad and the Innocent

Copyright 2020 by Albert Etzerza

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Tellwell Talent

www.tellwell.ca

ISBN

978-0-2288-4179-1 (Hardcover)

978-0-2288-4178-4 (Paperback)

978-0-2288-4180-7 (eBook)

Table of Contents

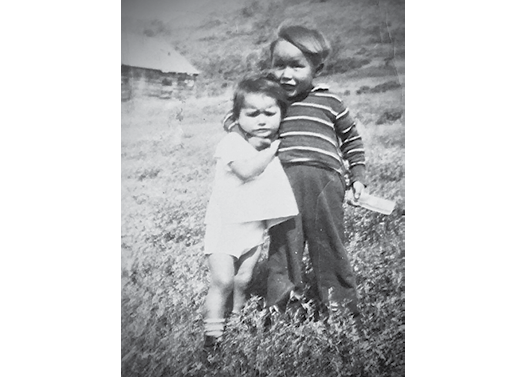

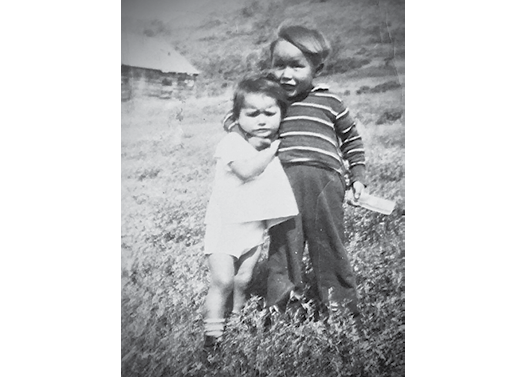

To the memory of my beloved mother (Mary Una Low) and younger sister, (Rose) whose love and understanding has encouraged me to write this memorandum. To my wife Rose and five boys, (the joy of my life) I trust they will have something I didnt have as a child: Freedom to speak their minds and seek a profession of their choice. May God have mercy on the souls of hypocrites who have negatively affected my life.

sister and bro ther

The first six years of my life were spent in what I consider to be the best of my childhood. Born to a single mother of two small boys, I quickly leant the true meaning of love. We were a close -k nit family. Because food was scarce, my mother decided to register us in school away from home (residential). Little did she know the devastating effect this institution would have on our l ives.

At the age of six, I was thrust into a routine of prayer and sexual molestation. The residential school preached prayer and penance. The hypocrisy of their attitudes was overwhelming. Not only was there constant beating for childhood antics, but the system attracted people who molested young children. They had complete control over First Nat ions.

At an early age, I quickly leant to excel in school and to submit to the molesting, which was very prevalent. We were taught that Natives (Indians) were lower than second -c lass citizens. Our existence on earth was solely to be taught by white superiors. The meaning of a (white) civilized world. This meant total obedience to their every command and inhuman n eeds.

Can you imagine thinking beatings are justified and molesting normal just because they were initiated by these so -c alled holy people? Did they really think that God would automatically forgive their wrongs because they were the messengers? If this was the way they thought, are they ever going to be surprised in death. God did not ok all the molesting; it was human error, issued on a pair of mitts and a jacket in winter that we had to make sure we didnt lose. Those who lost mitts or a jacket were sent out anyways. The weather was usually 20 F and sometimes dropped to - 4 F. Those who ran away (which was a frequent occurrence) were shaved bald.

Further punishment consisted of a public strapping in front of the entire student body and staff. The strap was leather, approximately three feet long, three inches wide, and a quarter inch thick. This was meant to cause much pain. The students were lined up with hands extended. The principal (priest) always did the deed. If the boy pulled his hands away, he was given extra. I can vividly remember the priest being exhausted from all the hitting. His red face will always remain in my me mory.

Watching this torture has affected me, and I am sure the rest of my Native sisters and brothers. My feelings are neutral, as I am not militant to the point of hate. I sometimes break down in tears but do not hate these people. At the same time, no love is projected. I have love, but it is well camouflaged by projecting no fee ling.

obedience was taught in the sc hool

W here

Where have all the good days gone?

Theyve faded into the past

Where have all the good days gone?

They were short and fast

We like to relish the good old days

Many would just as soon fo rget

We like to relish the good old days

I sometimes sit and wo nder

Why days seem lo nger

Where have all the good days gone?

Theyve faded into the past

Where have all the good days gone?

They were short and fast

Remember when you sm iled

Try to focus on that tho ught

Remember when you sm iled

It was the end of a dro ught

We can rely on happy t imes

To make our past a distant me mory

Sc hool

Where have the children gone?

They were here yeste rday

Where have the children gone?

They were taken during the day

Did they really have a ch oice?

I see no one in rej oice

The tears that are shed

Are tears of sorrow and woe

The tears that are shed

Are not false and do not flow

But rather pour relent less

Resisting is power less

They herd us in trucks like ca ttle

The cold winds of fall s ting

There are too many to cause a ra ttle

We huddle close to avoid the fall wind

You see we had no ch oice

What is there to rej oice?

As I left the sunny skies of Tahltan, my soul descended into a massive cloud, which has not cleared since. My two older brothers (eight and ten) had no idea that our innocent lives were about to change forever. Accompanied by Mom and our younger sister, the ride from Tahltan to Dease Lake seemed like a lifetime. My only memory of that trip was the car sickness I felt in my stomach. I was not punished, as my mother was present. I entered the system in the fall of 1951 and didnt get out for any summer vacations until June of 1957. Six years without a breath of fresh air. What did we do to deserve this?

My mother thought it was a dream come true. Not only were her children getting an education, but she was hired as a baker in the newly built residential school in Lower Post, B.C. She was approached by the Indian agent and priest with a promise of being there with her children. As we would obtain a much -n eeded education, she relented. She later told me that the happiness of not being separated from her children was more than she could hope and pray for. Her employment was short -l ived . A year later, she was terminated because she was not the baker desired. To save money, it was the policy of this particular school to leave out certain necessary ingredients. This left the bread heavy and Mom refused to bake bread, which she said was barely ed ible.

My mother moved to Prince Rupert, B.C. and we lost her presence at the school. It was two long years before we saw her again. We, along with a few other students, were forced to spend the summer months confined in the residential sy stem.

For whatever reason, Ive come to understand that poverty was why our mother could not take us out of the residential system until that year. She saved money and made a special trip from Prince Rupert to spend a couple of weeks with us. She rented a cabin and took us out for two glorious weeks. All too soon, she had to leave. Holding back tears, I soon broke down in a fit of sobs as my older brother c ried.

I will never forget the words my supervisor said to me. He said, I cant understand why you have any reason to cry. After all, you have me. In his twisted mind, he actually thought that his weird ways were what I was looking forwar d to.

Next page