This book could not have been completed without the assistance and cooperation of many individuals. I am most grateful to the Commissioners G. Erasmus, R. Dusssault, J.P. Meekison, V. Robinson, M. Sillett, P. Chartrand, and B. Wilson for having provided the opportunity to undertake this research and for their determination that no documentary stone be left unturned in a search for information about the school system.

The project researchers F. McEvoy, S. Heard and I owe thanks to staff and consultants at the Royal Commission: D. Culhane, M. Castellano, A. Reynolds, N. Schultz, N.-A. Sutton, L. Forbotko, R. Chrisjohn, D. Reaume, all of whom provided generously much-needed support, direction, and invaluable advice. The staff of the Oblate, Anglican, Presbyterian, and United Church Archives, and the National Archives of Canada were most cooperative in identifying sources and making files available. At the Department of Indian Affairs, K. Douglas facilitated research on the closed INAC collection, making a difficult situation manageable and productive; and John Leslie, an expert on the history of the Department, provided advice and direction. Computer, clerical, and editorial assistance were provided by K. Cannon, Managing Editor of the Journal of Canadian Studies; Carol Little at the Trent University History Department; Jessa Chupik-Hall, M.-J. Milloy, and Bridget Glassco.

Special thanks are owed to Professor G. Friesen for his advice on recasting the manuscript, on moving it from report to book, and, in that venture, to the members of the Manitoba Studies in Native History Board and the staff at the University of Manitoba Press, particularly Director, David Carr, and Managing Editor, Carol Dahlstrom.

Finally, I owe a sizeable personal debt to Clare Glassco, Jeremy Milloy, Bridget Glassco, M.-J. Milloy, and Molly Blyth for unstinting support and understanding in what has been, over the last five years, an all-consuming and too-often cheerless project.

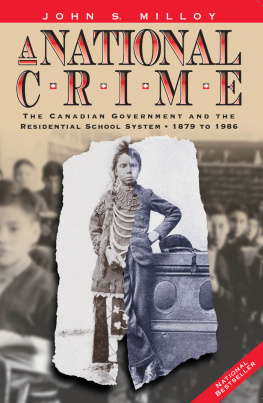

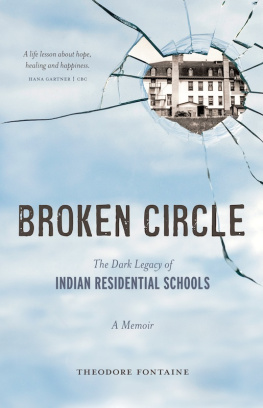

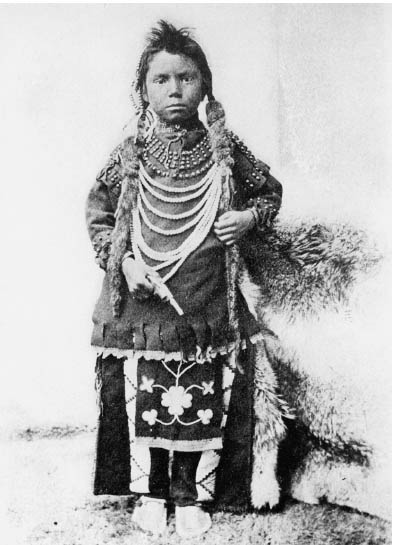

A potential pupil (Anglican Church of Canada,

General Synod Archives, P75-103, S8-21, MSCC)

Residential Schools in Canada, 1931

In 1931 there were 44 Roman Catholic (RC), 21 Church of England (CE), 13 United Church (UC) and 2 Presbyterian (PR) schools. These proportions among the denominations were constant throughout the history of the system.

In Quebec two schools, Fort George (RC) and Fort George (CE), were opened before the Second World War. Four more were added after the war: Amos, Pointe Bleue, Sept-Iles and La Tuque.

Source: Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Looking Forward, Looking Back, Vol. 1 of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Ottawa: Canada Communications Group, 1996.

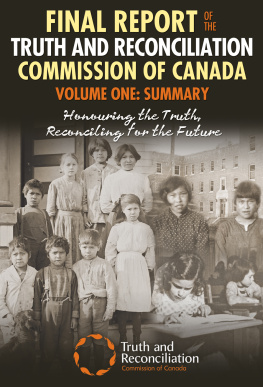

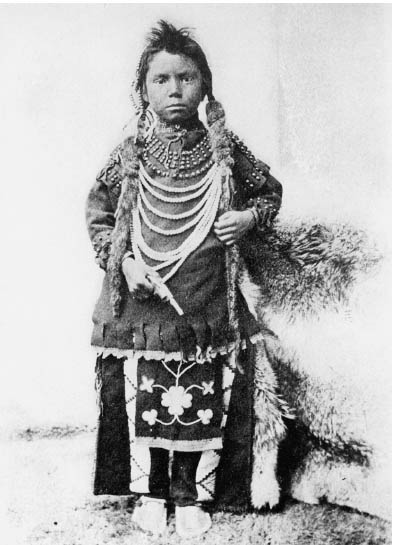

In its Annual Report of 1904, the Department of Indian Affairs published the photographs of the young Thomas Moore of the Regina Industrial School, before and after tuition. The images are a cogent expression of what federal policy had been since Confederation and what it would remain for many decades. It was a policy of assimilation, a policy designed to move Aboriginal communities from their savage state to that of civilization and thus to make in Canada but one community a non-Aboriginal one.

At the core of the policy was education. It was, according to Deputy Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott, who steered the administration of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, by far the most important of the many subdivisions of the most complicated Indian problem.

The pictures are, then, both images of what became in this period the primary object of that policy: the Aboriginal child, and an analogy of the relationship between the two cultures Aboriginal and White as it had been in the past and as it was to be in the future. There, in the photograph on the left, is the young Thomas posed against a fur robe, in his beaded dress, his hair in long braids, clutching a gun. Displayed for the viewer are the symbols of the past of Aboriginal costume and culture, of hunting, of the disorder and violence of warfare and of the cross-cultural partnerships of the fur trade and of the military alliances that had dominated life in Canada since the late sixteenth century.

Thomas Moore, as he appeared when admitted to the Regina Indian Industrial School (Saskatchewan Archives Board, R-82239 [1])

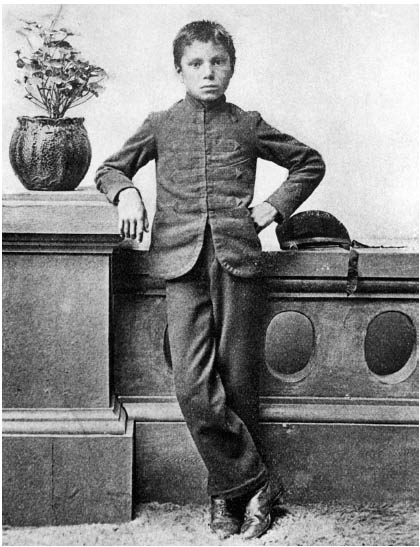

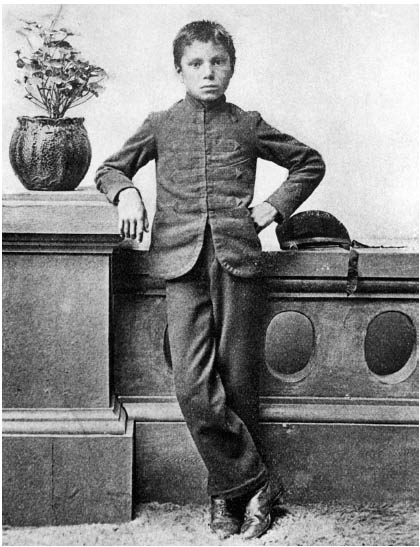

Thomas Moore, after tuition at the Regina Indian Industrial School (Saskatchewan Archives Board, R-82239 [2])

Those partnerships, anchored in Aboriginal knowledge and skills, had enabled the newcomers to find their way, to survive, and to prosper. But they were now merely historic; they were not to be any part of the future as Canadians pictured it at the founding of their new nation in 1867. That future was one of settlement, agriculture, manufacturing, lawfulness, and Christianity. In the view of politicians and civil servants in Ottawa whose gaze was fixed upon the horizon of national development, Aboriginal knowledge and skills were neither necessary nor desirable in a land that was to be dominated by European industry and, therefore, by Europeans and their culture.

That future was inscribed in the photograph on the right. Thomas, with his hair carefully barbered, in his plain, humble suit, stands confidently, hand on hip, in a new context. Here he is framed by the horizontal and vertical lines of wall and pedestal the geometry of social and economic order; of place and class, and of private property the foundation of industriousness, the cardinal virtue of late-Victorian culture. But most telling of all, perhaps, is the potted plant. Elevated above him, it is the symbol of civilized life, of agriculture. Like Thomas, the plant is cultivated nature no longer wild. Like it, Thomas has been, the Department suggests, reduced to civility in the time he has lived within the confines of the Regina Industrial School.

The assumptions that underlay the pictures also informed the designs of social reformers in Canada and abroad, inside the Indian Department and out. Thomas and his classmates were to be assimilated; they were to become functioning members of Canadian society. Marching out from schools, they would be the vanguard of a magnificent metamorphosis: the savages were to be made civilized. For Victorians, it was an empire-wide task of heroic proportions and divine ordination encompassing the Maori, the Aborigine, the Hottentot, and many other indigenous peoples. For Canadians, it was, at the level of rhetoric at least, a national duty a sacred trust with which Providence has invested the country in the charge of and care for the aborigines committed to it.

In Canadas first century, that truly patriotic spirit would be evident in the many individuals who devoted their human capabilities to the good of the Indians of this country. In the case of Father Lacombe, Oblate missionary to the Blackfoot, for example, the poor redmans redemption physically and morally was the dream of my days and nights. With the assistance of church and state, wandering hunters would take up a settled life, agriculture, useful trades and, of course, the Christian religion.