CAMPAIGN 261

PYLOS AND SPHACTERIA 425 BC

Spartas island of disaster

| WILLIAM SHEPHERD | ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS |

Series editor Marcus Cowper

CONTENTS

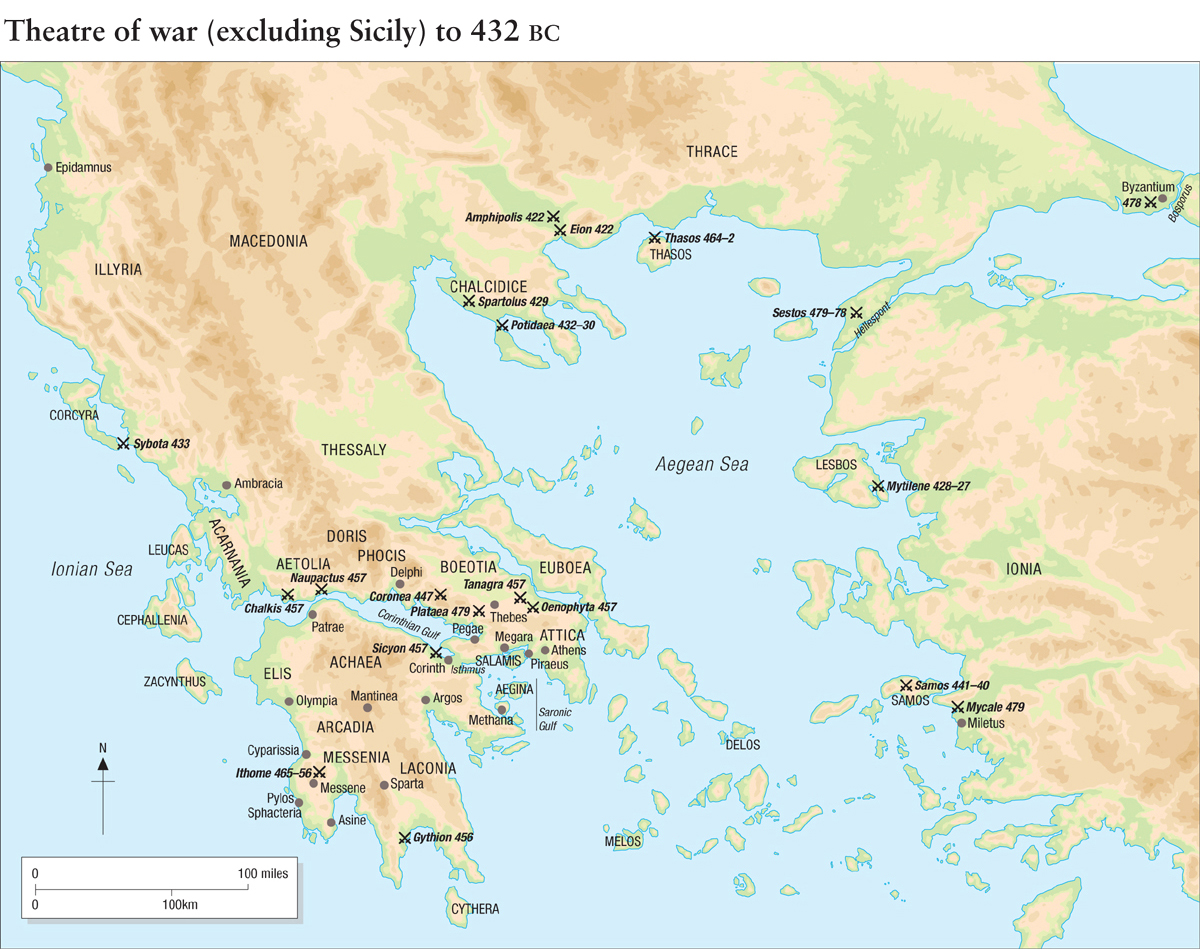

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

479460 BC

In 479 BC , immediately after the victories of Hellas (the ideal, never actually achieved, of a united nation of all the Greeks) over the Persians at Plataea and Mycale, the Athenians persuaded those who had fought at Mycale to bring the liberated Greeks of Ionia into the Hellenic Alliance for their long-term protection. This was against the wishes of the Spartans, who had argued that they should be repatriated from Asia. The Hellenic fleet then sailed to the Hellespont to destroy Xerxes bridges of boats, which had actually already been dismantled in 480 BC . Considering their mission accomplished, the Peloponnesian contingent went home. However, the Athenians, led by Xanthippus, the father of Pericles, stayed on and captured Sestos, establishing it as one of their most important overseas naval bases.

Immediately after the battle of Plataea and the surrender of Thebes, the Athenians had set about rebuilding their city and its walls against the strongly expressed wishes of the Spartans, who were nervous of Athens recently acquired strength, so powerfully demonstrated in the war against the Persians. According to Thucydides, the Spartans did not make any show of anger with the Athenians but were privately angered at failing to achieve their purpose.

In 478 BC , Pausanias, the Spartan regent who had led the Greeks to victory at Plataea, took a Hellenic fleet to Cyprus, conquered most of the island and then sailed north and took the city of Byzantium from the Persians, gaining control of the Bosporus. However, at this point, the rest of the Greeks rejected Spartan leadership on the grounds that Pausanias was now acting more like a tyrant than a general (Thucydides I.95: all subsequent Thucydides references are given with book and paragraph numbers only). They placed themselves under the Athenians, who almost immediately started to raise contributions from allies to support the collective effort of defending Hellas from Persia. These funds were to be administered by Athens but held on the sacred island of Delos, and the voluntary alliance known as the Delian League had come into being. In not much more than a year the first roots were put down of the conflict that would, from 459 BC , so violently split Hellas for most of the rest of the century.

The League was successful in its purpose of protecting Hellas from Persia. By the time of its great victory on the Eurymedon River on the north shore of the eastern Mediterranean in 466 BC , it controlled the whole of the eastern Aegean and the western coastal strip of Asia. Sparta played no part in the Eurymedon campaign. A year or so later the important island of Thasos seceded and it was to take an Athenian expeditionary force two years to bring about its return to the League. The Thasians appealed to the Spartans for support, which suggests there was some expectation that it might be given.

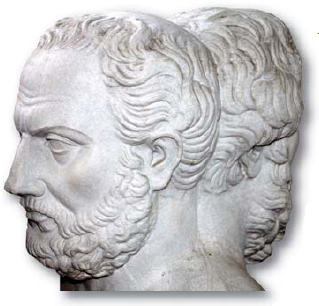

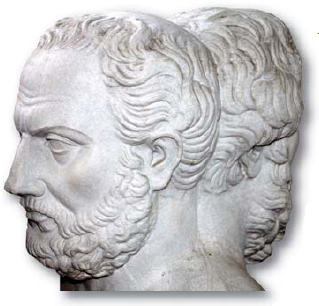

Portrait of Thucydides (c.455395 BC ) back-to-back with Herodotus (c.485425 BC ) in a Roman copy of a Greek double bust. Herodotus account of the Persian War stands as a massive evolutionary stepping stone between the archaic oral tradition of narrative of the past and the recognizably modern history-writing of Thucydides. Thucydides superb account of the Peloponnesian War is regarded as a foundational text in Western political thought. It is also an excellent source for the military historian because Thucydides lived through this war and served Athens, at least competently, as a general in it. He deals with the Pylos campaign in the first third of Book IV of the eight books of his unfinished history, which takes the conflict to 411 BC , seven years before Spartas final victory. Sicily 415413 BC is the only campaign covered at greater length. Naples Museum.

However, that year Sparta was struck by a massive earthquake, which killed tens of thousands and flattened most of their buildings, and also by a rebellion of their Helot subjects in Messenia, their third since the Spartans conquered them in the 7th century BC . By 462 BC the Spartans had the Messenians contained in Ithome, their mountain stronghold, but were making no further progress. They had little expertise in siege warfare, most probably because they had no taste for it.

They called on the Athenians, still formally their allies, for help and they sent a large force under Cimon. He was son of Miltiades, the victor of Marathon, and had led the Greeks to victory at Eurymedon. But, in Thucycidides words, the first open difference between the Spartans and the Athenians came about because of this campaign. The siege dragged on. The Spartans became increasingly nervous that the Athenians, with their more liberal attitudes, might become dangerously sympathetic with the enemy, so they told them they were no longer needed. The Athenians took offence, breaking off the alliance that had been formally in place since the Persian invasion and entered new ones with Spartas old enemy, Argos, and with Thessaly, threatening Spartas friends in Boeotia. Finally, they began work on the long walls that would connect the city securely with Piraeus and the sea. The roots of conflict had spread wider and deeper.

THE FIRST PELOPONNESIAN WAR 459446 BC

In 459 BC the Athenians made a landing on the Peloponnese at Halieis. It is not known if this was intended as an act of war or if the purpose was simply to beach for the night and obtain food and water by reasonably peaceable means, but a force from Corinth confronted the Athenians and defeated them. Their ship-borne hoplites were probably outnumbered and the much larger throng of light-armed rowers and seamen who also landed would have been quite easily overwhelmed. Immediately after this the Athenian fleet defeated a Peloponnesian fleet off the island of Cecryphalia west of Aegina. These were the opening clashes in the 13 years of conflict known as the First Peloponnesian War, and immediately fitted the general strategic pattern of Peloponnesian superiority on land and Athenian superiority at sea.

Then the Athenians went to war with Aegina, an enemy in the past and historically aligned with the Peloponnese, to force the island into the Delian League. Around this time Megara voluntarily joined the League, pulling out of the Peloponnesian Alliance because of border disputes with Corinth. This city was strategically placed on the main route between the Peloponnese and Attica and Boeotia, and controlled the ports of Pegae on the Corinthian Gulf and Nisaea on the Saronic Gulf.

Greece was still at war with Persia and the Athenians had diverted a large force from operations against Persian interests in Cyprus to support a revolt against Persian rule in Egypt. Artaxerxes, the Great King, tried without success to use Persian gold to persuade the Spartans to invade Attica to make the Athenians withdraw from Egypt. The Corinthians saw the Athenians heavy commitment on two fronts, Aegina and Egypt, as an opportunity to take Megara back. However, the Athenians mobilized their reserves, the old and the young above and below campaigning age, marched the 50km into the Megarid and fought the Corinthians to a draw in a closely contested battle. Both sides claimed victory but a second battle a few days later ended decisively in the Athenians favour.