Campaign 99

Fuentes de Ooro 1811

Wellingtons liberation of Portugal

Ren Chartrand Illustrated by Patrice Courcelle

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

I n October 1810, the outlook appeared optimistic for Napoleon I, Emperor of the French. The last 20 years of his life had been truly amazing: in 1790, he was an obscure young subaltern officer in the French artillery who disliked France and yearned to liberate his native Corsica. Five years later, he was a general in the French army leading his troops to victory in Italy; in 1800, he was the most important of the three consuls that governed France; by 1805, he had been crowned emperor and had vanquished Austria; by 1810, Prussia and Russia had joined Austria in defeat and the French imperial eagles were unchallenged from France to Poland. Napoleon had even succeeded in coaxing the reluctant Pope to grant him a divorce from the barren Empress Josphine. This allowed him to marry young Princess Marie-Louise of Austria in order to bear an heir to the imperial throne as well as to seal a pan-European alliance. On 27 March 1811, Empress Marie-Louise gave birth to a sturdy baby boy. Napoleon was overjoyed. The baby was given the name of Napoleon and made King of Rome. A successor to the imperial throne seemed assured.

On one occasion, Napoleon had surprised his mother, who was busy with her investment bankers, making fun of her and saying that she was past such worries as the Bonapartes ruled Europe and all its riches. Letitia Buonaparte, who had known poverty and want in her younger years, answered that such confidence was foolish, that one never knew what could happen or lay ahead so that it was always wise to save for rainy days. The emperor shrugged and left.

Napoleon meets Francis II, Emperor of Austria, following the great French victory at Austerlitz on 2 December 1805. From then on, Napoleon saw himself more as emperor of Europe. (Print after Gros)

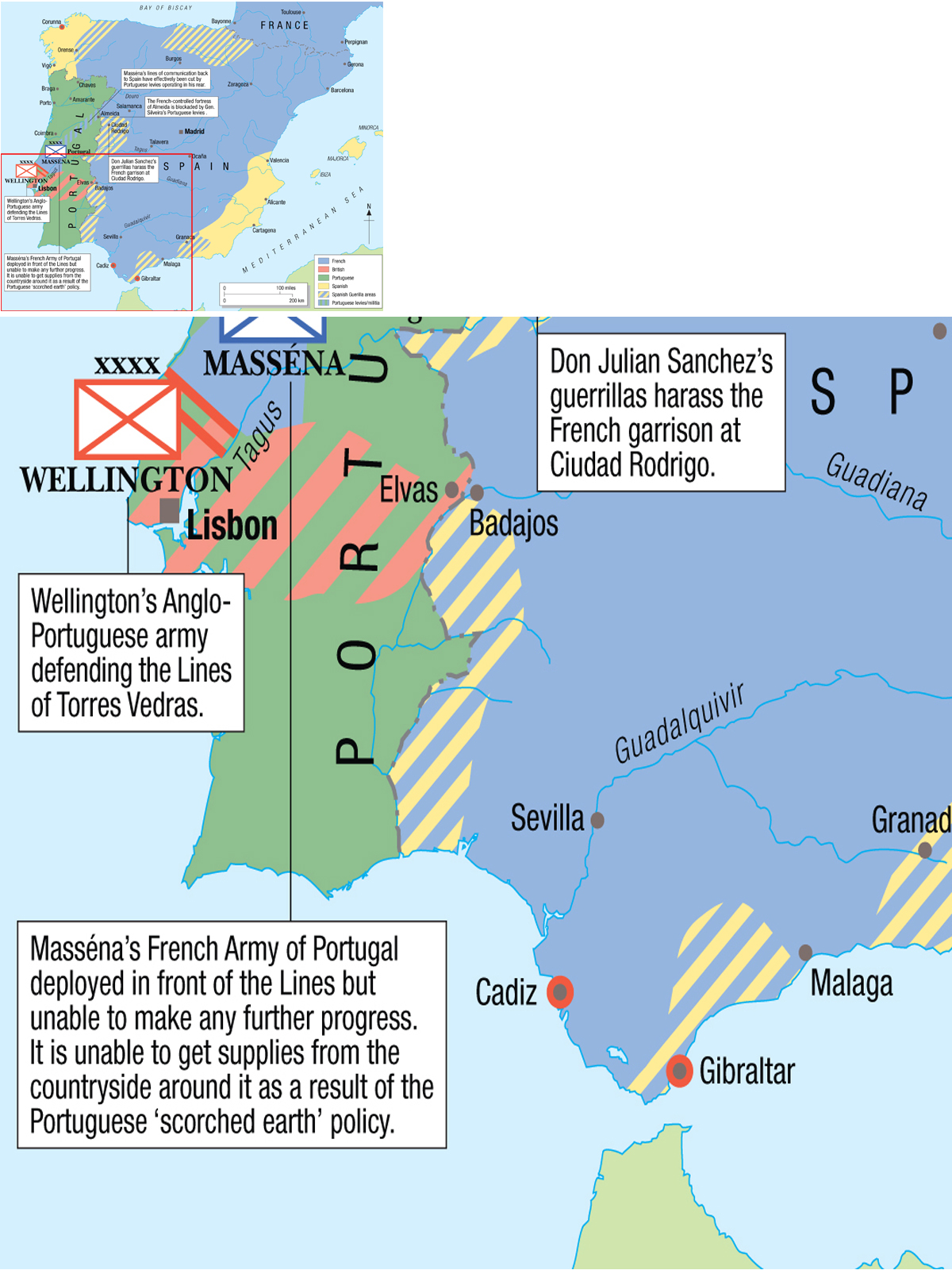

In some ways, the first of those rainy days for Napoleons imperial regime had come on 11 October 1810 in far-away Portugal. That day, the French cavalrymen pursuing the retreating Anglo-Portuguese army reached the lines which appeared to block, at least temporarily, the advance of Marshal Massna and his French Army of Portugal. They also constituted an irritating delay to Massnas triumphant entry into Lisbon after months of difficult campaigning. At first, these lines were thought to be some last minute field works thrown up by Wellingtons retreating army, but they were strangely uniform in construction. General of Division Louis-Pierre Montbrun, the French cavalry commander on the spot, ordered parties of scouts to reconnoitre. Patrol after patrol of dumbfounded cavalrymen galloped back to Montbrun and his staff officers reporting that the network of cleverly sited fortifications extended along the hills as far as they could see in either direction. In addition, far from being rough, hastily erected earthworks, some appeared to be major forts bristling with cannon and full of soldiers.

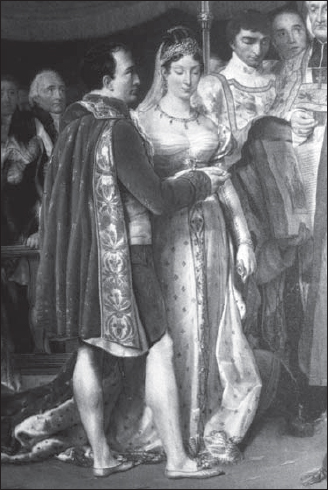

The marriage of Napoleon to Marie-Louise of Austria celebrated at the Louvre in Paris on 2 April 1810. (Print after Rouget)

What these scouts had in fact encountered were the soon-to-be-famous Lines of Torres Vedras, one of the most sophisticated integrated defence systems yet devised. Although not clear at the time, the French army had reached its high water mark in the peninsula.

Watching the progress of the French armies in Spain and Portugal on a map in Paris, it must have seemed to Napoleon and his senior officers that at last they were about to witness the final act of the war in the Iberian peninsula. Soon, the couriers from Massnas army would announce the embarkation of the British army evacuating the Portuguese capital and its occupation by the French army. With the only major force capable of resisting the French out of the way, other opposition in Spain and Portugal would ultimately collapse.

Indeed from the British viewpoint the situation in Portugal was far from cheerful in 1810. Years after the war, Sir John Colborne, the future Lord Seaton, who had served within Wellingtons army at the time, skilfully summed it up: Between the months of February and August, 1810, the affairs of the Peninsula appeared almost hopeless. Andalusia had quietly submitted [to the French]. The last large army of the Spaniards had been dispersed. Seville was occupied Massna had taken Ciudad Rodrigo, was besieging Almeida, and preparing to march on Lisbon through Beira with an army of about 70,000 [men]. Lord Wellington manoeuvred in Beira and in the Alemtejo with an army of about 50,000 English and Portuguese. He had to contend against a Ministry frightened at the risk of exposing a British army and while he, unmoved by their fears, was carrying into execution one of the most scientific campaigns of those days, the British Ministers were thinking of preparations for embarking the troops He also had to contend against another faction of the Portuguese Government that imagined he was withdrawing. As soon as it became know that his intention was to retire ultimately on Lisbon, the Bishop of Porto drew up a strong remonstrance, in which he threatened that the Portuguese troops should be withdrawn from Lord Wellingtons command if he did not defend the frontier.

In the event, the fortress of Almeida was destroyed in a disastrous explosion and, full of confidence, the French swept into Portugal until they reached Bussaco. There, on 27 September 1810, Wellingtons Allied army gave the French a severe rebuke, which dampened their morale while raising the hopes of the British and Portuguese. Colborne wrote his sister Alethea two days later that this action very much changed the appearance of affairs in Portugal. The Portuguese troops have established their character They behaved in a most gallant manner, and full as well as the British. As can be seen from contemporary correspondence, including that of King George III, the performance of the Portuguese was a great encouragement to the British. The front opened against the French in the Peninsula had seemed full of promise with the massive risings in Spain and Portugal in 1808 against Napoleons rule. Two years later, the picture seemed very gloomy to anyone in Britain. As heroic as the Spanish could be, their hopelessly inefficient regular armies had been repeatedly crushed, and what Spanish government that remained seemed quite hostile to the British to be fair, Britain was Spains ancient enemy and certainly deeply suspicious of Britains motives. Even rumours of some partial British control of troops or territory could create a major diplomatic crisis between Spain and Britain.

Next page