Campaign 140

Monongahela 175455

Washingtons defeat, Braddocks disaster

Ren Chartrand Illustrated by Stephen Walsh

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T he events related in this book led to a general war, since known as the Seven Years War, between France and Great Britain with their respective allies, that was eventually fought on four continents and culminated in Britains triumph. The early events at Jumonville Glen, Fort Necessity and at the disastrous field near the Monongahela River have since been overshadowed by the wars subsequent course and by the career of George Washington, destined to become one of the most famous men in modern history.

King Louis XV of France. In the middle of the 18th century, the realm of this somewhat debonair king included parts of southern India and much of North America. This empire, created largely through the efforts of his grandfather Louis XIV, would be lost within the next two decades. Portrait made in 1746 by Maurice-Quentin de La Tour. (Authors photo)

As will be seen, these early battles ended in utter defeat for the Anglo-American troops at the hand of the French and Indians, generally seen since as barbarous enemies by generations of American and British historians. However, a closer examination of the French show most of them to have been native-born Canadians, and the Indians to have been independent peoples won over by their long-standing diplomatic ties with New France. Furthermore, it becomes clear that the French and Indian method of fighting was no lucky accident but a conscious tactical doctrine which, ironically, was ignored in France while, after the disaster at the Monongahela, it was eagerly adopted by both British and Americans.

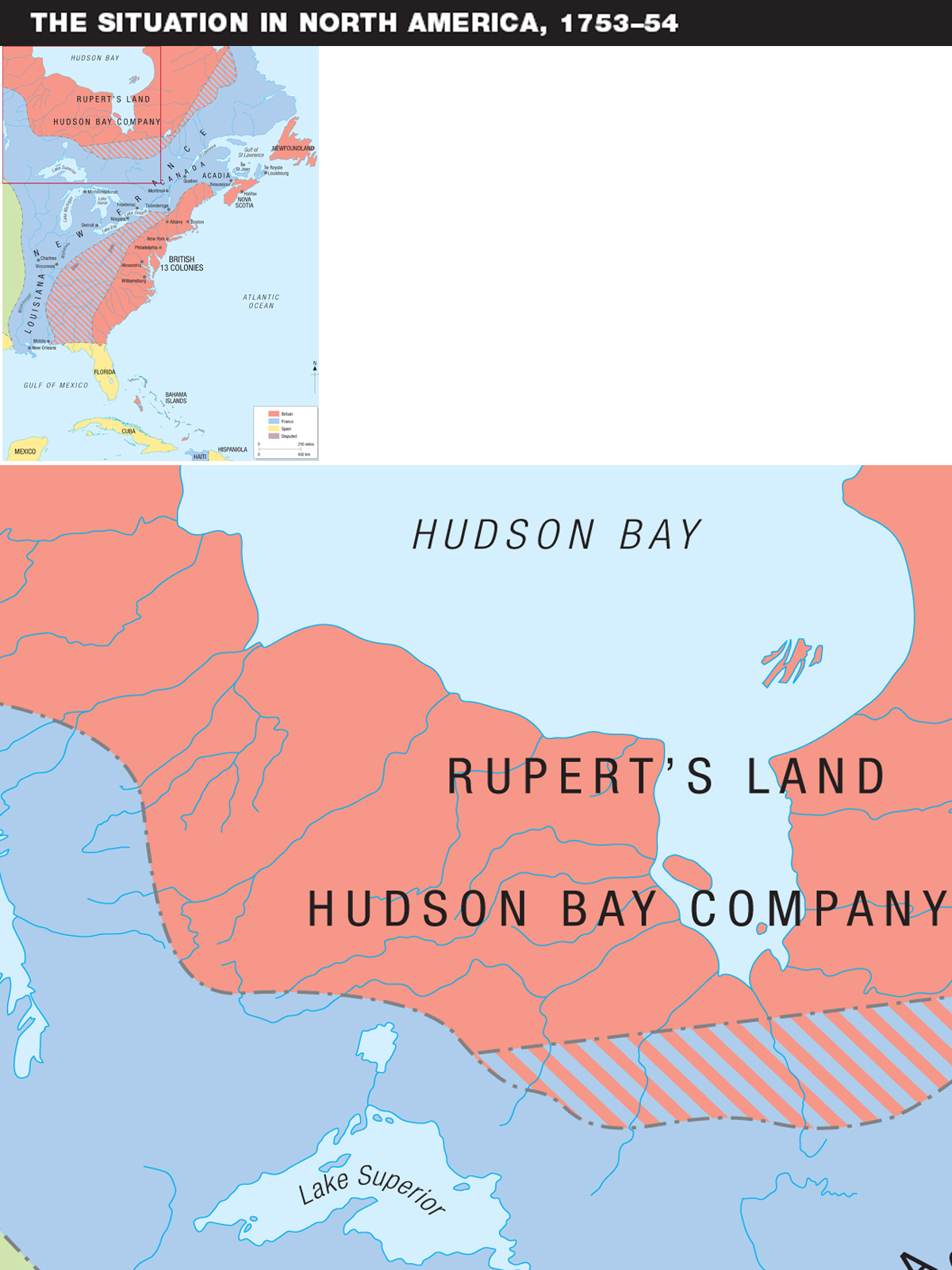

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

During the 17th and the first half of the 18th centuries, the British and French colonies in North America, by the very nature of their respective development as well as the frequent wars of their mother countries, were once again moving towards a major confrontation. The British flag flew over a number of colonies stretching from Georgia to Newfoundland along the Atlantic seaboard that were, for the most part, rapidly growing and populous entities. By the middle of the 18th century, the population of the American colonies included well over 1,000,000 souls of European descent. The larger colonies such as Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and South Carolina had their own local legislatures, large populations and prosperous economies thanks to the continuing development of agriculture, shipping, trade, and commerce. In spite of some efforts by the Crown to rationalize administration with royal governors, the American colonies remained very independent. They were also quite different from one area to another. The northern colonies, such as Massachusetts, had been settled by religious refugees who often held a Puritan and religiously conservative outlook on many of lifes issues. The colonists of the middle colonies had more varied origins and New York, for instance, still had a sizeable Dutch population and corresponding traditions. Pennsylvania, although a major trade center thanks to the city of Philadelphia, was still politically dominated by the pacifist sect known as the Quakers. Of the southern colonies, Virginia was the most important and depended largely on the expanding plantations that gave its society a more distinctive class structure with the large estates and more genteel way of life of its social elite. The government of the British colonies in North America was very decentralized, with each having its own legislative assembly and policies. For all these reasons, in time of war it was difficult to mobilize the colonies into a concerted effort.

Fur traders and Indians. The fur trade was at the root of the rivalry that led Britain and France to war. In the middle of the 18th century, the French largely controlled the interior of North America and its fur trade, but mounting pressures caused by increasing numbers of Anglo-American traders wandering into the Ohio Valley led to confrontation. Detail for a map of the inhabited part of Canada from the French Surveys by C.J. Gaulthier published in 1777. (National Archives of Canada, C7300)

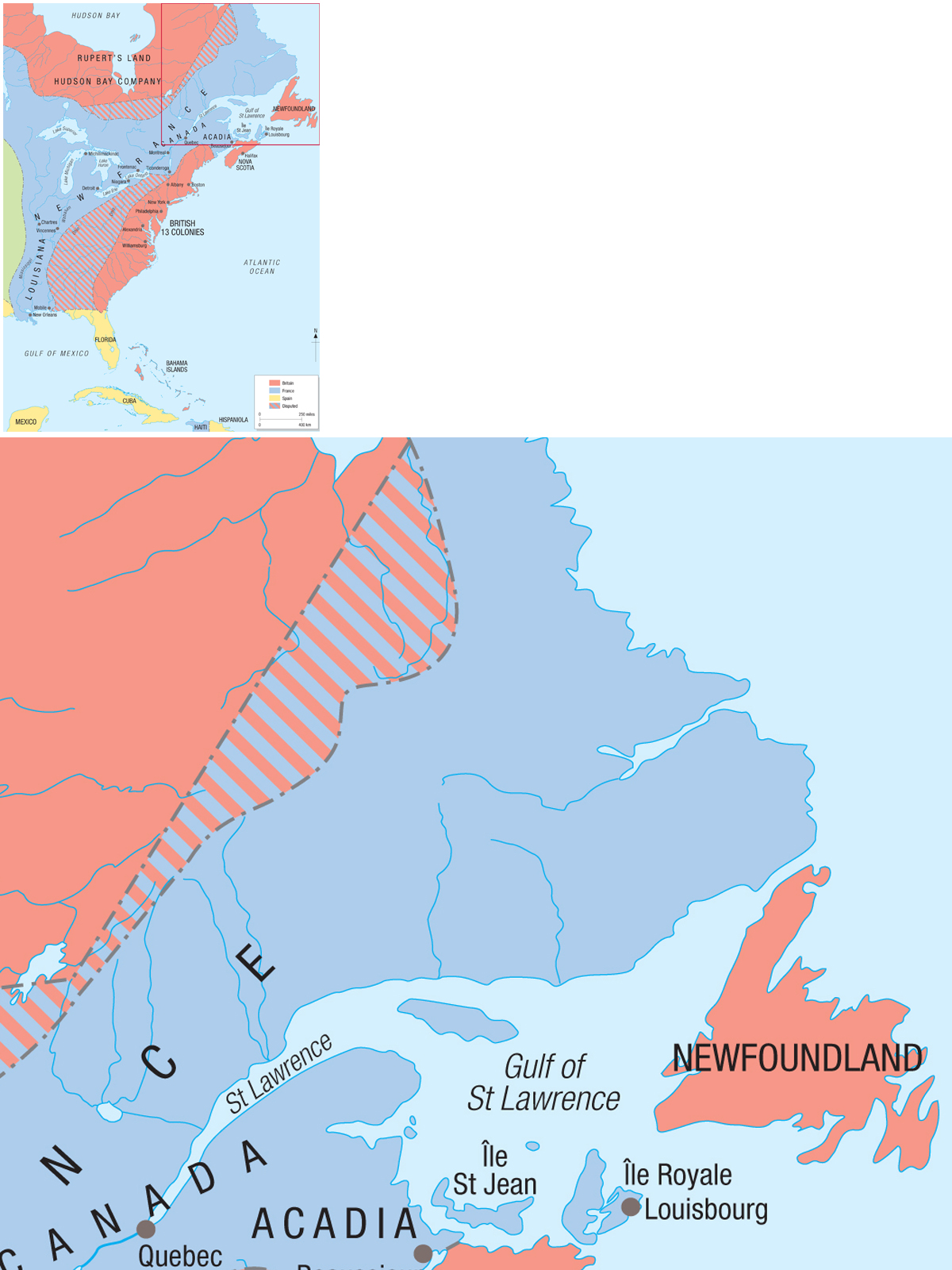

New France, by contrast, penetrated deep into the hinterland of North America thanks to outstanding explorers such as Samuel de Champlain who went to the Great Lakes in the early 17th century, Robert Cavelier La Salle who reached the Gulf of Mexico during 1682 by navigating the Mississippi River, and a captain of colonial troops, de La Vrendrye, and his sons who built trading forts in the Canadian prairies and penetrated as far as the Rocky Mountains in present-day Wyoming in the 1730s and 1740s. Except for Cape Breton Island and its fortress and naval base of Louisbourg, built from 1720, France had few coastal settlements until one reached Mobile and New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico. New France had developed in the interior of the vast North American continent, happy to leave the British colonists to the eastern seaboard and a few posts on Hudson Bay, and the Spanish to Florida and northern New Spain (the present Texas and American Southwest).

There was no gold or silver found in New France and its economic mainstay was the fur trade. To facilitate this trade and maintain its territorial claims, a far-reaching network of forts was built at strategic sites along the shores of the hinterlands rivers and lakes. This network formed a great arc running from the Gulf of the St Lawrence River through the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. The European population of New France was minuscule and concentrated at either end of this arc: Canada in the north with its approximately 60,000 inhabitants concentrated along the shores of the St Lawrence River; Louisiana with only 5,000 or 6,000 settlers on the Gulf coast and another 2,000 or so established in the Illinois Country, also called Upper Louisiana, in the area where the Missouri and Ohio rivers flowed into the Mississippi. Several thousand African slaves had also been transported into Louisiana. As for the indigenous Indian population, it is practically impossible to calculate an accurate figure; many eastern nations had been decimated by epidemics of European diseases in the 17th century but sizeable populations remained, while many western nations were all but unknown to Europeans. The government of New France and its components was autocratic, as was France under the Old Regime. There were no legislative assemblies. The governor general had overall authority, as did the intendant, in financial and civic matters and the bishop in religious issues, with powers devolved to local governors, commissaries and senior priests. In spite of a seemingly rigid autocratic structure, it was necessary to exercise power wisely as all actions had to be approved by senior officials in France who had channels of information and news over and above official reports. One of the benefits of the centralized system of governance in New France was that it was comparatively efficient at mobilizing the colonys relatively meager resources for military purposes.