I honor him.

I slew him.

PREFACE

The Fault Line

W e all know the story: how a defiant and undisciplined collection of citizen soldiers banded together to defeat the mightiest army on earth. But as those who lived through the nearly decadelong saga of the American Revolution were well aware, that was not how it actually happened.

The real Revolution was so troubling and strange that once the struggle was over, a generation did its best to remove all traces of the truth. No one wanted to remember how after boldly declaring their independence they had so quickly lost their way; how patriotic zeal had lapsed into cynicism and self-interest; and how, just when all seemed lost, a traitor had saved them from themselves.

C harles Thomson was uniquely qualified to write a history of his times. As secretary of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1789, he had functioned as what one historian has described as the prime minister of the Congress. While delegates came and went over the course of the War of Independence, Secretary Thomson was always there to bear witness to the behind-the-scenes workings of the nations legislative body during its earliest and most critical period. According to his friend John Jay, no person in the world is so perfectly acquainted with the rise, conduct, and conclusion of the American Revolution as yourself.

Soon after his retirement in July 1789, Thomson set to work on a memoir of his tenure as secretary to the Congress, eventually completing a manuscript of more than a thousand pages. But as time went on and the story of the Revolution became enshrined in myth, Thomson realized that his account, titled Notes of the Intrigues and Severe Altercations or Quarrels in the Congress, would contradict all the histories of the great events of the Revolution. Around 1816 he finally decided that it was not for him to tear away the veil that hides our weaknesses, and he destroyed the manuscript. Let the world admire the supposed wisdom and valor of our great men, he wrote. Perhaps they may adopt the qualities that have been ascribed to them, and thus good may be done. I shall not undeceive future generations.

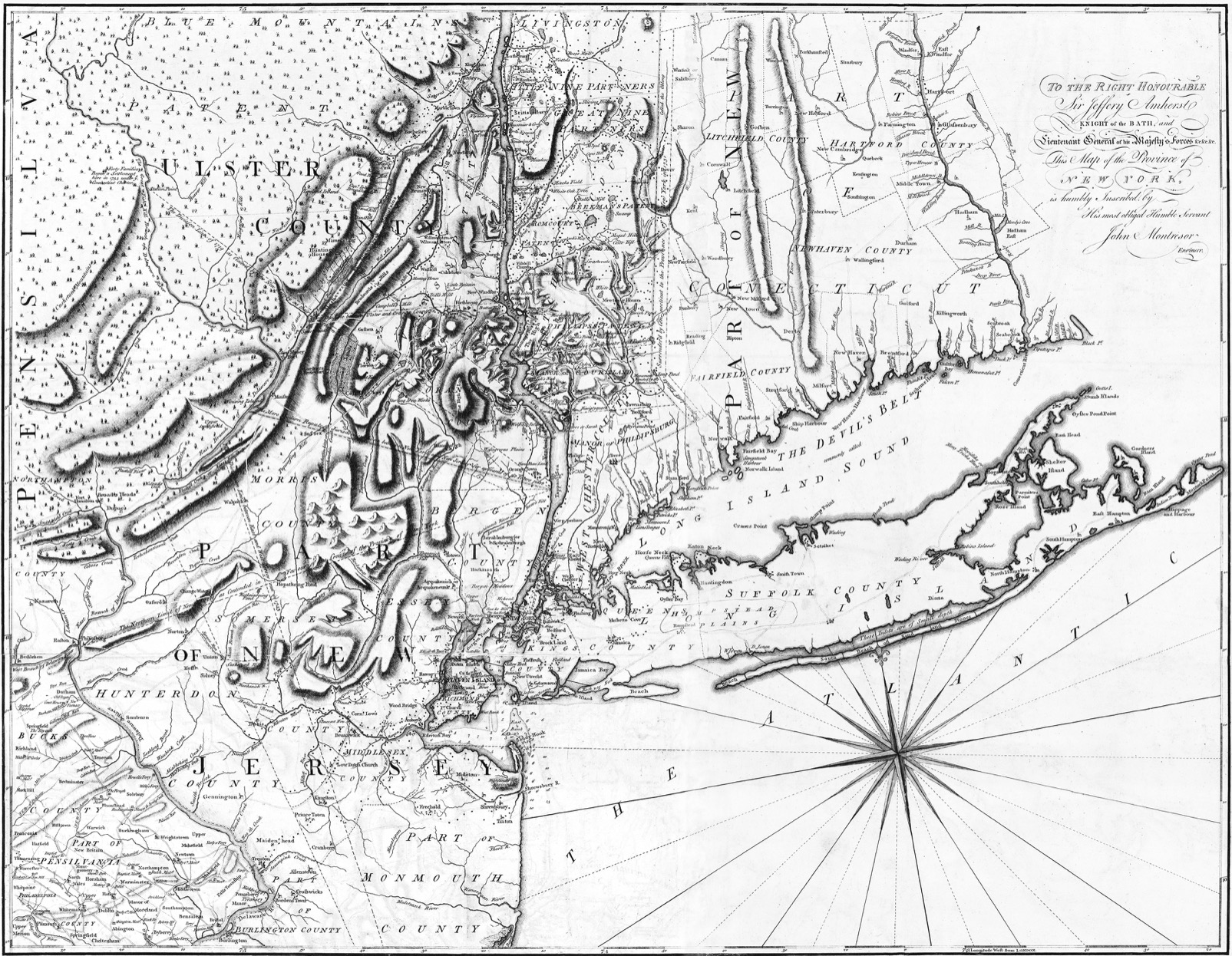

T he American Revolution had two fronts: the war against Great Britain and a civil war so widespread and destructive that an entire continent was seeded with the dark inevitability of even more devastating cataclysms to come. Many of us have heard of the partisan struggles in the South during the final bloody years of the Revolution. But the middle of the country was also torn apart by internal conflict, much of it fought along the periphery of British-occupied New York. Here, in this war-ravaged Neutral Ground, where neither side held sway, neighbor preyed on neighbor in a swirling cat-and-dog fight that transformed large swaths of the Hudson River Valley, Long Island, and New Jersey into lawless wastelands.

At the epicenter of this self-destructive furor was the patriot capital of Philadelphia. Before and after it was briefly occupied by the British, the city was the scene of religious and political persecution, profiteering, and massive legislative dysfunction. Rather than the paragon of leadership and eloquence that we associate with the passage of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the Continental Congress had become, as the testimony of Charles Thomson suggests, the political incarnation of the confusion and hostility that had overtaken the nation as a whole.

By the summer of 1780, America had reached its lowest ebb. The expectations created by a dramatic victory at Saratoga in 1777 had subsided into disillusionment as the much-vaunted alliance with France had so far done nothing to win the war. Exhausted and dispirited by a struggle that was in its fifth year, the American people appeared to have turned their backs on the cause they had once so ardently embraced. Instead of a unified republic governed by a Continental Congress, the United States had devolved into thirteen scrabbling and largely independent polities. If, by some miracle, General Washington should find a way to win the war against the British, the real question was whether there would be a country left to claim victory.

What follows is the story of how one of Washingtons greatest generals came to decide that the cause to which he had given almost everything no longer deserved his loyalty. Although it later became convenient to portray Benedict Arnold as a conniving Satan from the start, the truth is more complex and, ultimately, more disturbing. Without the discovery of Arnolds treason in the fall of 1780, the American people might never have been forced to realize that the real threat to their liberties came not from without but from within.

T he Battle of Saratoga is the pivot point of this story, the place where on October 7, 1777, Benedict Arnold suffered the debilitating injury that ultimately set him on the path to treason. It is also where his nemesis Horatio Gates acquired the renown that allowed him, with the help of key members of the Continental Congress, to challenge Washingtons position as commander in chief.

Washington is rightly regarded today as one of the greatest military commanders and statesmen in American history. But like every exceptional leader, he made his share of mistakes. Indeed, to insist that Washington could do no wrong is to deny him his greatest attribute: his extraordinary ability to learn and improve amid some of the most challenging circumstances a commander in chief has ever faced.

As he was valiant,

As he was valiant,