TOMAHAWK AND MUSKET

French and Indian Raids in the Ohio Valley 1758

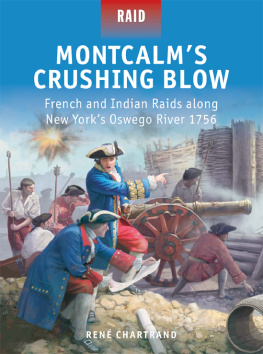

REN CHARTRAND

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

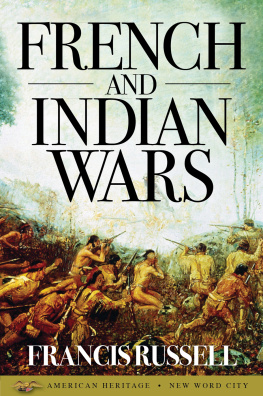

In the histories of the Seven Years War in North America, the campaign by General Forbes to reach the Ohio Valley in 1758 has always been overshadowed by the more spectacular Ticonderoga campaign and the taking of Louisbourg, both of which occurred during that year; and also by the disastrous 1755 defeat suffered by General Braddock near the Monongahela, so that Forbes campaign three years later is treated somewhat as an afterthought.

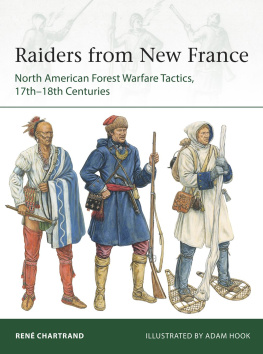

It has to be admitted that the 1758 campaign did not produce a major engagement in a huge battlefield. No great charges; no great generals. Much of the Anglo-American armys activity centered on road- and fort-building. Oddly enough, many accounts and, particularly, American histories of the conflict, seem more fascinated by these construction endeavors than by the fighting that did indeed take place. Perhaps because the one Anglo-American raid on Fort Duquesne, led by Major Grant, turned out to be a monumental fiasco and because the French raid on Fort Ligonier was such a success, to the point where this author suspects some denial on the part of rather patriotic historians. However, the core of the problem is probably the paucity of the accounts regarding both raids. It is remarkably difficult to find good, let alone detailed, first-hand accounts of both actions. There are no precise contemporary maps or illustrations, sometimes no maps at all, of the actions. Historian Douglas R. Cubbison has published a fine account of Forbes army quoting extensively British and American sources. In this study, we contribute many French accounts to the record, some published for the first time in English.

As readers will see in the following pages, we have had to make many assumptions as to the approximate location of even the general actions during a raid, let alone details on a particular aspect. Some may be open to question, but, on the whole, we hope it gives a good general view of these two very large raids of the last years of what Americans often call the French and Indian War.

ORIGINS

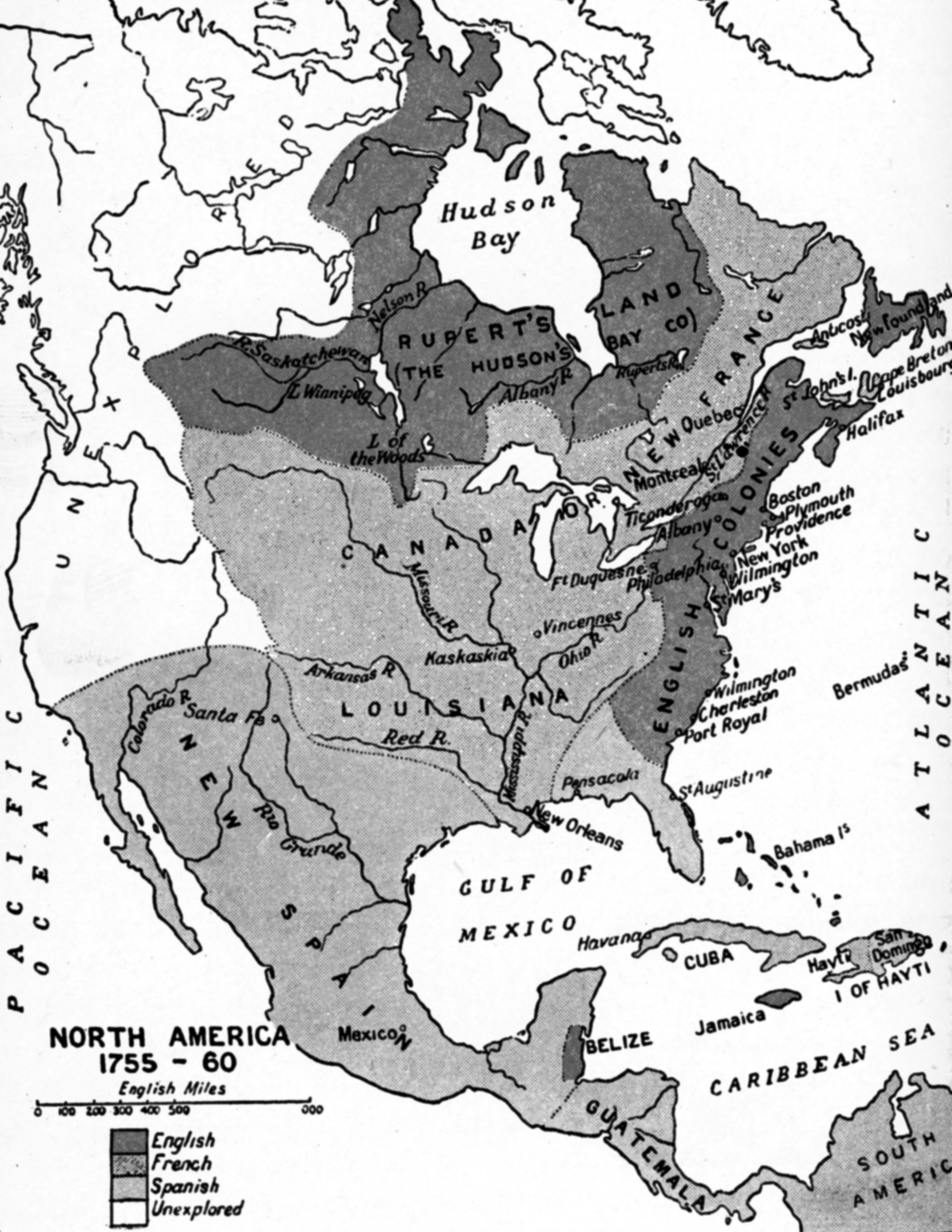

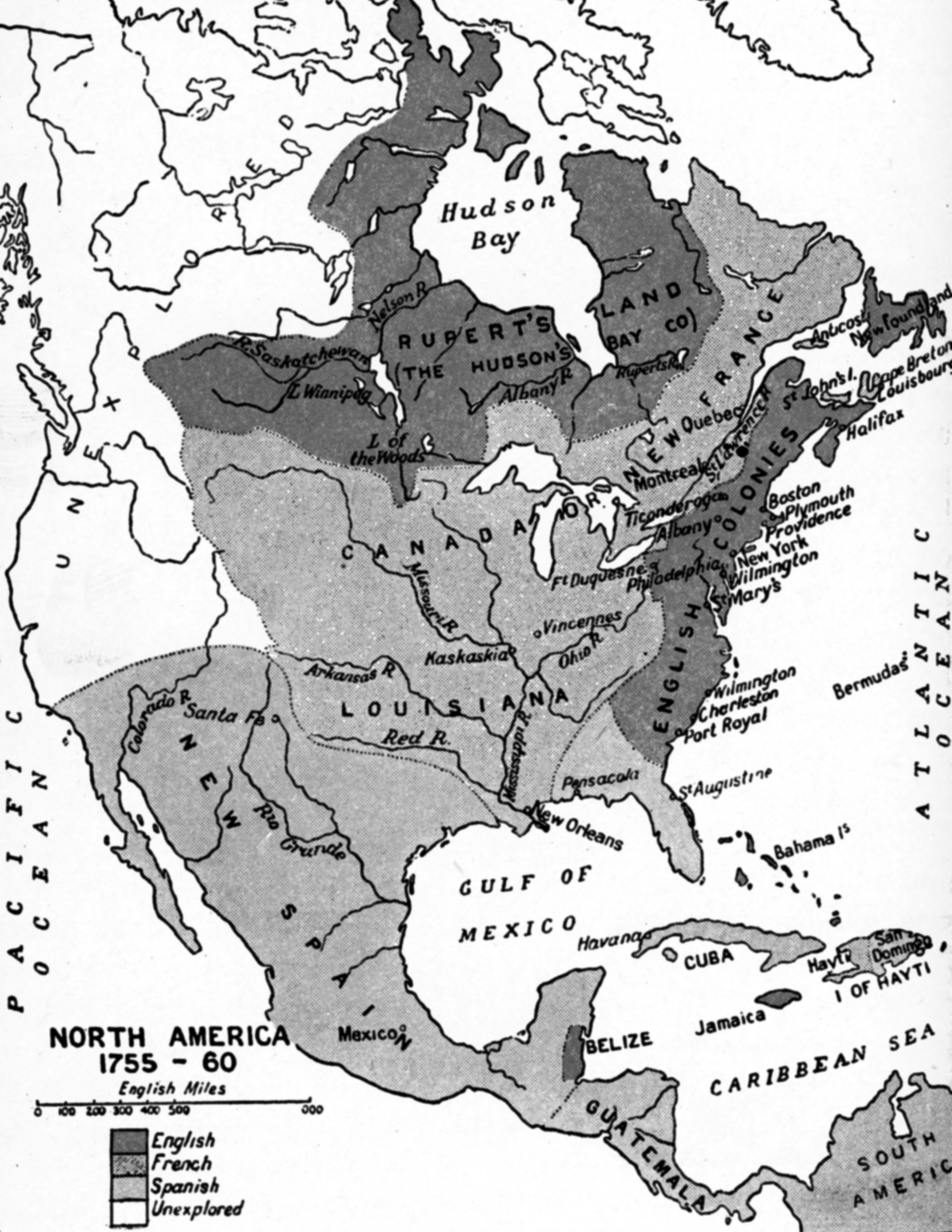

In the middle of the 18th century, North America was claimed and partially occupied by three major European powers: Spain, France, and Great Britain. Spains domain was largely to the south, encompassing the vast viceroyalty of New Spain that comprised present-day Mexico, Central America, the larger West Indian islands, Florida, and much of the American southwest. This huge territory was not, however, in a great rivalry with the colonies of the other two powers.

New France covered a vast area extending from the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River in Canada to the Rocky Mountains westward and to the Gulf of Mexico southward, forming a sort of huge crescent across the middle of the continent. It was sparsely populated with French settlers, who by the mid-18th century probably numbered no more than 65,000 souls mostly living in Canada along the shores of the St. Lawrence. There were perhaps another five or six thousand more in Louisiana going from the Gulf to Illinois, while about a further four thousand were in the port fortress city of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island. While agriculture played an important role along the shores of the St. Lawrence, fur was Canadas main export so Canadian fur traders roamed over vast expanses to trade with the Indian nations who were, in fact, the true masters of the primeval forest and the vast rolling prairies.

The smallest group of colonies was the one over which flew Great Britains flag, which occupied the mainlands seaboard from Nova Scotia to Georgia. These various colonies were originally settled by groups of Englishmen, Dutchmen, and Swedes that had been joined by many Scots and Germans later on. By the middle of the 18th century, the population of the British colonies along the Atlantic seaboard hovered at around a million and a quarter. Many were merchants and seafarers, but most farmed plots of land. The British colonies were extensively settled with farms and plantations, and featured several large cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. The territories of these colonies were restrained to the east of the Appalachian Mountains. As population grew, the pressure to find new western land increased.

Map of North America in the 1750s. Spain, France, and Great Britain had various claims to substantial parts of America, much of it, such as Ruperts Land or western Canada, unsettled by European powers. (Authors photo)

In terms of military command and of the ability to marshal forces, the far less populous New France had the advantage. It was, since the 1660s, administered by the royal French government and therefore generally organized, with various allowances for place and distance, like a French province. The capital was Quebec City, the port of entry to Canada, and the place of residence of the governor-general, who was both the highest official in New France and the governor of Canada, the most important part of the domain, going from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the western prairies. On the east coast, Acadia and southern Newfoundland had been lost to Britain by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, but France had built the sizable fortress city of Louisbourg on Isle Royale, as Cape Breton Island was then called, and this area was set up as a separate colony with its own governor. Louisiana had been settled from the early 18th century on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico and up the Mississippi River to the Illinois Country south of the Great Lakes, and it had its own governor residing at New Orleans. In matters of command and policy, the governors were the supreme commanders of the forces within their respective colonies; they formulated the diplomatic ties with the Indian nations, and reported to the minister of the navy and colonies in France, who himself reported to the king and was part of his council. It was an autocratic form of government from top to bottom, and while each governor had to have a superior council made up of the colonys most eminent civilian and religious leaders, there was no such thing as an elected assembly.

All three of Frances North American colonies were each provided with a garrison of regular colonial troops, the Compagnies Franches de la Marine (independent companies of the navy) with a few companies of gunners. Those at Isle Royale were nearly all in Louisbourg. In Canada and Louisiana, a core of these troops were posted in cities such as Quebec, Montreal, Detroit, New Orleans, and Mobile, while the rest were spread out in the many forts built along the French trade routes. By 1758 the official New France military establishment came to 99 regular colonial infantry companies and four artillery companies, making a theoretical total of some five thousand officers and men. But too few recruits and replacements had been sent and the actual strength was probably about a third less. A peculiar feature was that from the late 17th century, and as years went by, the officers of these troops were increasingly born in Canada. By the middle of the 18th century, a large majority of officers were Canadian gentlemen. The enlisted men were recruited in France and after their period of service officially six years, but this often varied they were encouraged to settle in Canada or Louisiana. About a quarter to a third of the soldiers were posted in the far-flung wilderness forts. These postings could be for periods of about two years, but some of the soldiers grew fond of life in remote outposts and some appear to have remained there the rest of their lives. When passing at Fort Michilimackinac, gunner J.C.B. (see bibliography) met a Compagnie Franche infantryman who had been there for 25 years. Some of these men became quite at ease in this wilderness environment and assimilated, largely from their Indian allies, the notions of bush warfare.