CONTENTS

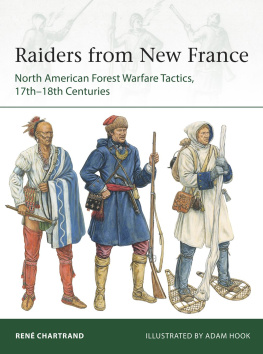

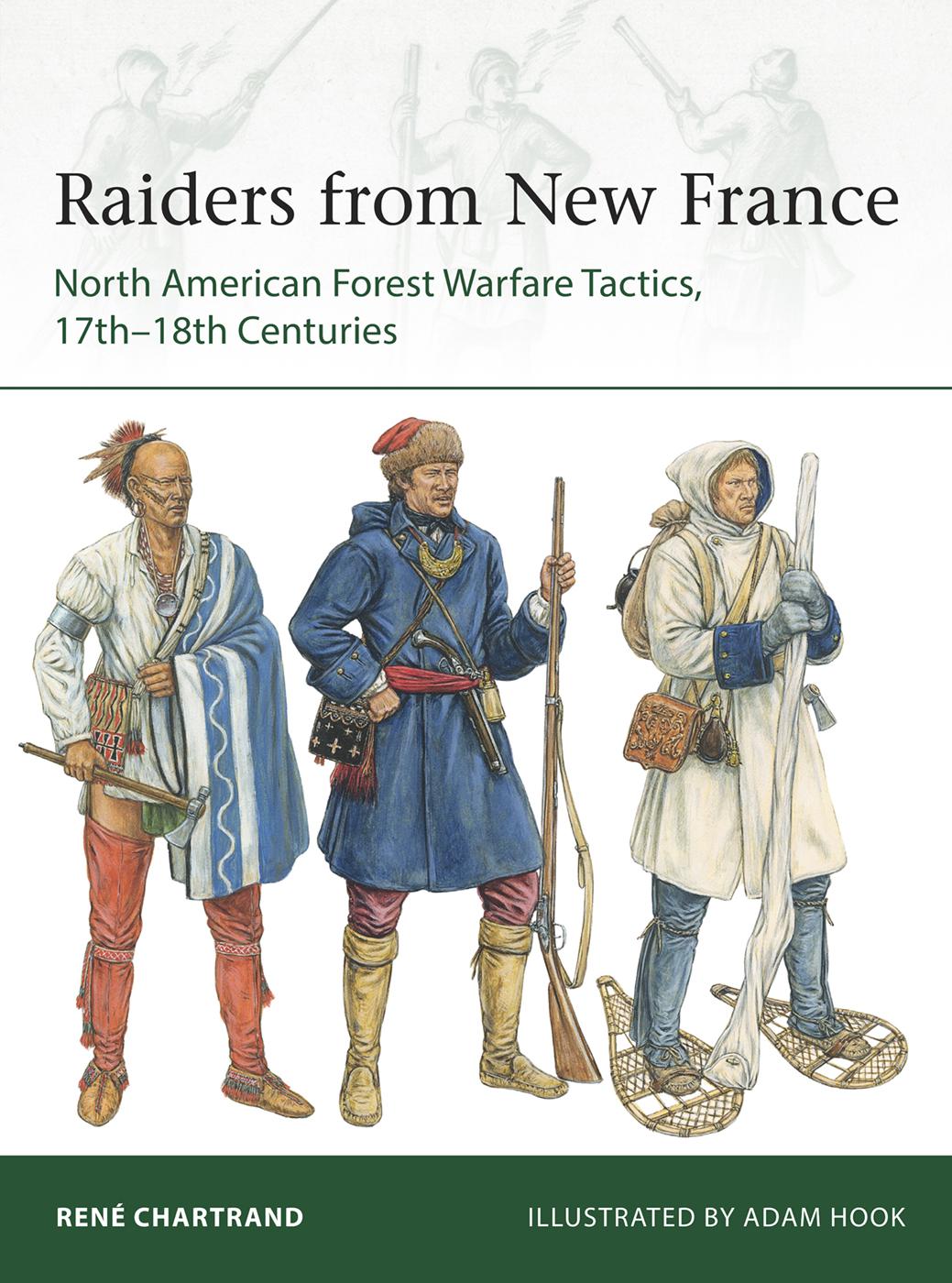

RAIDERS FROM NEW FRANCE

NORTH AMERICAN FOREST WARFARE TACTICS, 17th-18th CENTURIES

INTRODUCTION

During what the anglophone world generally calls the French and Indian Wars, the tactics of surprise attacks and raids launched from within New France kept the Anglo-American colonies on the Atlantic seaboard in a defensive posture for three-quarters of a century. Meanwhile, by mounting audacious expeditions, the French settlers though less numerous by a factor of ten came to dominate trade in immense wilderness areas from the Gulf of St Lawrence down to the Gulf of Mexico, and explored as far west as the Rocky Mountains. The object of this study is simply to explain how this came about, and to identify the leaders who devised and promoted the tactics that had such extraordinary geo-strategic consequences.

The challenge faced by New France was not only to keep the faster-growing Anglo-American colonies contained, but also, when diplomacy and trade agreements failed, to vanquish hostile First Nations. Success in both objectives was achieved by the creation of a superior fighting force with a longer reach. There were no manuals describing how to fight in the North American wilderness; but by collating various memoirs and documentary records, and by analyzing actual expeditions as well as the important material-culture aspects, we can discern a fascinating picture. Thanks to visionary officers who formed and maintained close relations with friendly First Nations, a successful Canadian European/Indigenous tactical doctrine became firmly rooted.

This engraving titled Canadian wearing snowshoes going to war on the snow, from 1722, is the only known contemporary image of a late 17thearly 18th century Canadian militiaman on campaign. It is in Volume 1 of La Potheries work, where he describes the 169697 conquest of British Newfoundland in which 124 Canadian raiders played a leading role. Some features are curiously rendered by a European engraver baffled by unfamiliar North American items such as snowshoes, moccasins, mitasses , beaded pouches, a flapped cap and capot. The muskets exaggerated buttstock hints at one of the buccaneer weapons occasionally seen in Canada. (Print after Bacqueville de La Potheries Histoire de lAmrique septentrionale , 1722; courtesy Library and Archives Canada, C10605)

THE BEGINNINGS

Champlain, Frontenac, and La Barre, 160885

That French permanent settlements in North America became a reality during the 17th century was thanks largely to Samuel de Champlain. His establishment in Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia) in 1604 was soon followed in 1608 by another at Quebec, which became the capital city of New France, and as decades passed other settlements such as Trois-Rivires (1634) and Montreal (1642) were founded further up the St Lawrence River.

At the outset, the French had befriended the Huron (Wendat) First Nation, and in 160910 Champlain and a few companions won battles against the redoubtable Iroquois by the use of firearms. In the late 1630s the Iroquois themselves obtained firearms from the Dutch and English colonies to the south, and by 1649 the Iroquois confederacy had largely wiped out or driven off the Hurons and then turned their attention to the French settlements. Parties of warriors would suddenly attack, kill or kidnap, then simply vanish into the forest. Colonists in Montreal and Trois-Rivires had to go armed whenever they left their homes.

By May 1660 the Iroquois menace had increased to such an extent that a detachment of 17 soldiers in a small fort were overwhelmed. The French colony was in fear of being wiped out until, in 1665, King Louis XIV sent out the regular Carignan-Salires Regiment to keep the Iroquois at bay. After both winter and summer military expeditions, the Iroquois agreed to a peace treaty in 1668, though relations remained tense. While the Carignan-Salires then returned to France, some hundreds of officers and men chose to remain as settlers. By now the French had become heavily involved in the lucrative fur trade, whose expansion demanded ever more extensive exploration of the continents interior.

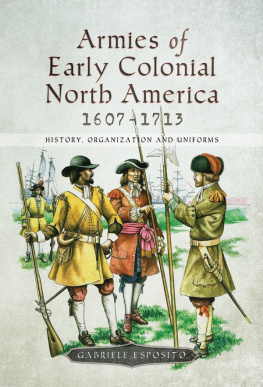

Regions of North America claimed by colonial nations, late 17th to mid-18th century. (From Lawlers Essentials of American History , 1902; authors photo)

Spirited impression of the last stand of Dollard des Ormeaux, commander of the weak Montreal garrison, who was killed with 16 companions when a small fort at Long Sault on the Ottawa River was overrun by an Iroquois war party in May 1660. The chronicler Dollier de Casson writes that the heavy casualties suffered by the Iroquois deterred them from attacking Montreal itself. (Print after R. Bombled; private collection, authors photo)

In 1672, Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac (162298), arrived in Quebec city as governor-general of New France. He was a career soldier who, under the great Marshal Turenne, had risen to an appointment as lieutenant-general when only 26 years old, and had later served the Venetian Republic in Crete until it was overwhelmed by the Ottoman Turks in 1669.

When Frontenac arrived at Quebec there were barely 65 soldiers in New France, including his own 20 guardsmen, but he quickly organized a staff with some of the retired officers. He was deeply impressed by North America, and on November 2, 1672, he wrote to Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert that nothing was so magnificent as the site of Quebec; this town cannot be better positioned [to] one day become the capital of a great empire. In 1673 Frontenac led an expedition that built a fort at Cataraqui, soon called Fort Frontenac (today Kingston, Ontario). Other forts followed, which became bases for crossing the Great Lakes and thence following the Ohio, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers, and gaining access to the Great Plains. In April 1682, the explorer La Salle would discover that the Mississippi flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, and claimed the whole area for France, naming it Louisiana.

For the defense of New France, Frontenac relied on the armed Canadian Militia, which had been organized into parish companies since 1669. Every able-bodied man aged from 16 to 60 was liable for duty, with officers and sergeants appointed in each parish, and regular company training. The use of firearms for hunting was very widespread, so that many settlers handled them expertly; furthermore, as time passed, increasing numbers were either veterans or the sons of soldiers. Frontenac also noted the remarkable military possibilities of the canoes used for inland trade along North Americas extraordinary web of rivers. These could be paddled and portaged over enormous distances by Canadian voyageurs or coureur-des-bois (travelers or woods-runners), who had become skilled in all aspects of forest-craft.

During Frontenacs administration, although the French colony had hardly any regular troops, the Iroquois generally stayed quiet while exploratory expeditions established new trade links with other First Nations. These too came to know Onontio the French Father, who ruled for the Great King over the seas. At Cataraqui in July 1673, Frontenac had reassured the assembled chiefs that he wished only friendship, and that he had wanted to meet them because it was important that a father should know his children and that children know their father. He apologized that he could not understand their language, but he had with him Charles Le Moyne a leading trader as his interpreter, so you will not lose a single word of what I said. Frontenac demonstrated an instinctive skill in the diplomacy required to deal with the First Nations and left a model for his successors (if they had the wit to follow it). Frontenac insisted that some Iroquois chiefs be present in 1673, and this went a long way towards maintaining a peaceful, if rather cool relationship between them and New France.