Pagebreaks of the print version

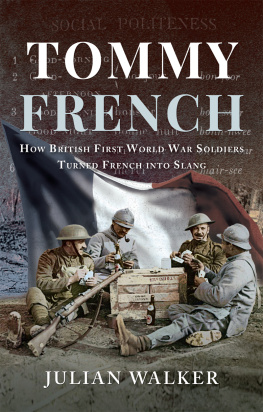

Tommy French

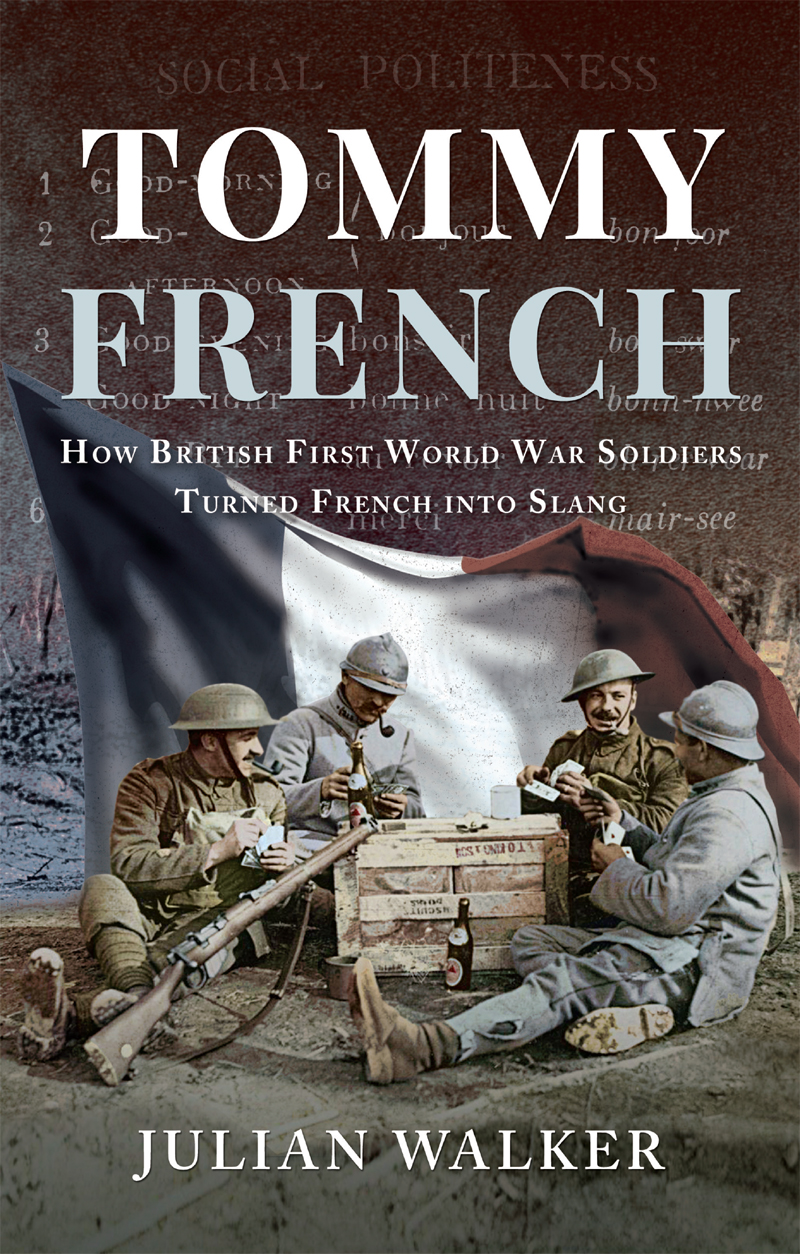

Tommy French

How British First World War Soldiers Turned French into Slang

Julian Walker

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Julian Walker 2021

ISBN 978 1 52676 592 5

ePUB ISBN 978 1 52676 593 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52676 594 9

The right of Julian Walker to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website:

To Christophe, friend and colleague

List of Illustrations

British-printed postcard, sent on Active Service, 1917

Soldiers phrasebooks from 1914 and 1915

Eugne Plumons V ade-Mecum

From Rapid-Fire French (1917)

From Glossary of Aviation Terms / Termes dAviation (1917); note the French adoption of looping

Postcard, sent On Active Service, December 1914

Stereoscopic photograph, Lessons in French not French lessons

Bombardier Fritz, from The Gasper , 6 January 1916

Postcard, Sammy trying his French on an old French Woman

Postcard in the series Sketches of Tommys Life , by Fergus Mackain, showing French children shouting Orangeez! Ah-pools! Shock-o-la!

Postcard, Du Pang

Cartoon from le Franais tel quon le parle, La Baionnette , 15 June 1916

Postcard sent from Berthe Brifort with studio photo picture

French erotic postcards sent from France

Postcard, This makes him smile somewhat

Postcard, Interpreter in Action , by M. Crete

Front cover of La Baionnette , 15 June 1916

Letter sent from France, May 1917; note the use of pas de field jour

Postcard sent On Active Service, 1916, with the words tray bon

From a letter sent October 1915, dropping in tres bon

From The Gasper , 8 January 1916

Postcard, Sister Susie

Postcard, Can you see the spot?

Advertisement for Boots, October 1916

Postcard sent May 1917, from Somme Where in France

Concert Party programme, Roubaix, February 1919

Postcard sent On Active Service, January 1919 (Im na-poo in this line)

Soldiers letter, sent to Catrine, Ayrshire, October 1917

Acknowledgements

M any thanks to Jonathon Green, Christophe Declercq, Chris Kempshall, Hillary Briffa, Julie and Peter Doyle, and Ryan Gearing, and particularly to Petonelle Archer and Vronique Duch, who read the manuscript and gave invaluable advice.

Introduction

S ome time ago, on a trip with some friends to the Western Front, we were settling ourselves onto the Eurostar when there was an announcement recommending that we keep an eye on our baggage, the French version ending with the phrase dquipages . One of my companions, with the quick verbal wit of a Merseysider, picked this up and asked, Dicky Parge? Is there a Dicky Parge on board? Dicky Parge immediately became a passenger on the train, to whom all kinds of mishaps and problems were attributed. On the way back a few days later we asked the train guard if anything untoward had happened to Dicky Parge; unsurprisingly, he did not get the joke.

The English relationship with the French language is indicative of the complicated and flexible relationship between the two nations and cultures. For 350 years after the Battle of Hastings the nobility preferred French to English, and speaking French was a way to get on in society, a social grace that was still evident in the nineteenth century. French has become the standard modern foreign language taught in schools, and for many in the twentieth century the foreign language they were most likely to have to use; singing classes in junior school in the 1960s included songs referring back to the wars against Napoleon. Caxton in the preface to the Aeneid , one of the first books printed in England, gives the story of a Yorkshire merchant who uses his own dialect to try to buy eggs from a woman in Kent; she does not understand him, and assumes he is speaking French, the archetypal foreign language. For over a thousand years, speakers of English have been mangling words from the French language and bringing them into their own speech. For this process, borrowing is the term usually used, curiously, where adopting might be more appropriate, though some terms have been returned to French often occasioning imagined or real grumbling by French linguists such as le parking, le challenge, or le coach. There is one famous term that shows this happening spectacularly rosbif, the name given to British soldiers on the Continent some time during the nineteenth century, possibly earlier. British soldiers were popularly supposed to eat roast beef, roast and beef both being words that moved from Anglo-Norman into Middle English during the Medieval period.

Borrowed or adopted words usually show an alteration of sound, as often happens when foreign words are adapted to suit home mouths; but sometimes English happily adopts the French pronunciation with little or no change, as in the case of chauffeur or baguette. Or there might be a compromise, as in garage or caf. We regularly use words that have been retained as obviously French ennui, double entendre, faux pas which bring no reaction from Spellcheck on the computer. Embracing a variety of adaptations of sound and spelling, English has taken thousands of French words and made them its own.

Possibly the most concentrated mangling of the French tongue in English-speaking mouths, and the subject of this book, involves British soldiers abroad again, between 1914 and 1919, as the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) found itself singularly ill-equipped to communicate with its nearest allies. The 1914 army was initially a regular force, most of whom had served in various colonial theatres, and if its soldiers had fluency in or familiarity with any foreign language it was more likely to be Urdu than French a soldier called Billy in 1914 was reported as trying to order a drink using English, Hindustani and Chinese, with one French word to help out. These, however, acted to make the language more distant from working-class and lower-middle-class standards.

During the First World War the major difference in this friendly nudging of French into English was that it took place largely on French soil, as millions of British soldiers, drivers, nurses, airmen, mechanics, clerks, engineers and doctors found that their knowledge of French, if any, was close to useless. For many of them French was neither intelligible nor necessary why for goodness sake didnt the blinkin Froggies speak English. Many French and Belgian people living and working in the areas where English-speaking soldiers were stationed (by 1916, only about 15 per cent of the people in unoccupied Belgium were Belgian) quickly learned English to realise the commercial potential of so many hungry and thirsty mouths. But even so, communication across languages is often governed by laziness if a working lingua franca can be created with the minimum of discomfort, then everyone is happy. For the soldiers there was frequently the need to communicate in situations that might have ramifications of life or death, making it necessary to learn recognisable versions of certain terms, concerning places, foods, procedures, equipment, situations, and people. Adopting and adapting, the soldiers, with a bit of help from the locals, created their own version of the Gallic language, which may be called Tommy French; this term indicates the role of the English-speaking soldier (not so much the officer) in constructing a version of French that was accepted and used by his comrades and by many French people. It was, as Brophy and Partridge say, something neither English nor French.