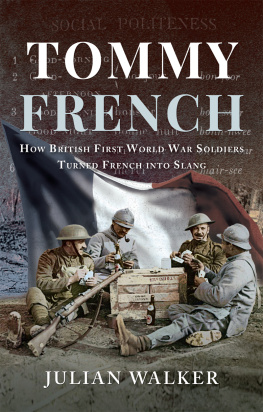

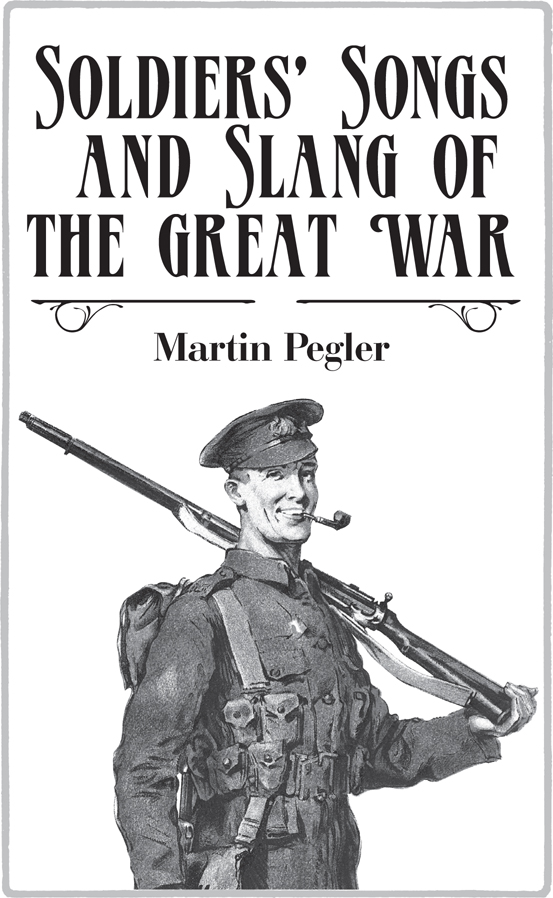

SOLDIERS SONGS AND SLANG OF THE GREAT WAR

To all of the Great War veterans we knew, whose courage, humour and modesty made them unique. It was a privilege to have known you all.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Lyn Macdonald, who introduced me to so many veterans of the Great War way back in the 1970s, and to Richard Dunning, who for the last 40 years had made it a personal crusade to prevent the Great War from becoming just another forgotten conflict. Thanks too, for help with images, to Clive Gilbert, Barry Lees and Peter Smith. Special thanks also to Kate Moore at Osprey who deemed this a worthy project, and Emily Holmes, who had to edit it! Last, but not least, to my long-suffering wife Katie, who has accepted with her usual tolerance my absences whilst I hid in my study, attempting to be creative.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I n a single volume there are limits as to how much can be covered in such a vast field as the songs, slang and terminology of the First World War. One could write (and indeed authors have written) books covering just one of the areas that this book encompasses. The first attempt to put all of this into a single volume was made by John Brophy and Eric Partridge in 1931 under the title Songs and Slang of the British Soldier. It was of necessity incomplete, leaving out much of the slang and verses of songs that were considered too crude for the rather more delicate sensibilities of the readers of that time. Although enlarged and updated in 1965 it remained heavily edited. It was, however, the first book on the Great War that I ever purchased and it was responsible for awakening my own interest, enabling me to be able to sing all of the songs from memory by the age of 12. Im sure my parents wished that they had a normal son who just liked the Beatles.

The 50th anniversary of the end of the war in 1968 did much to raise awareness of the subject and the subsequent release of the remarkable film Oh What A Lovely War in 1969 reached new audiences who would not normally have regarded the First World War as anything other than a distant historic event. My wife and I were very fortunate in the late 1970s and early 1980s to visit and interview dozens of veterans; their conversation was often peppered with the language of the trenches and it took little persuasion to start them singing long-forgotten songs. I made as many notes as I could, and these have miraculously survived assorted house moves and a disastrous fire.

It seemed to me, with the approach of the centenary of the war in 2014, that it was time for a properly updated and enlarged version of Brophy and Partidges work, so I have incorporated as much as possible of their material into this book. Of course, due to space constraints I have had to be selective in some areas but the text covers the most commonly found words, expressions and songs of the period, including those words considered, not so many years ago, to be obscene.

A surprising number of songs will still be familiar to us, such as If You Were The Only Girl In The World and Im Always Chasing Rainbows but it is probably the slang that will cause the most surprise, as so much of our language today still uses words and phrases that first saw the light of day in the trenches of France and Flanders. As common examples, people often refer to their loose change as shrapnel and of course everyone chats to friends, but few understand that the widespread dissemination of these words was a result of the war. Gradually these and many other words and phrases have been absorbed into modern English, without anyone really noticing. Still more expressions, such as over the top, have been recently reinvented, albeit with a slightly altered meaning.

I sincerely hope that this book will enlighten, amuse and occasionally surprise the reader. If I have missed out any vital entries (and Im sure I must have) I apologise and any errors contained are, of course, entirely mine. I hope youll find the subject as fascinating as I have done.

Martin Pegler

Combles, France.

T he English language reflects our old and very mixed culture, and like most languages it i snot static. It continues to change with time, many words falling out of use, whilst others are adopted and sometimes adapted. As an example of how much it has changed, try reading a text in 14th-century English. It is all but incomprehensible to anyone but a specialized historian. Even much of the English of Shakespeares time is now bewildering to our modern eyes, as those who recall having to study it at school will know. Latin, Norse, Germanic and French words have all contributed to what we know and speak today. Whilst every generation thinks of its language as contemporary, much of the English spoken by the men of the Great War generation was that of the previous two or three centuries. In addition, at the turn of the 20th century, there were huge linguistic differences to be found within the regions of the British Isles, possibly more so than there are today, for there was no standardized BBC English. Regional accents and words were quite unintelligible to men from different areas. At the turn of the 20th century this mattered very little, as few men travelled outside of their native areas to work or live, but that was to change dramatically post-1914.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that arrived in France in 1914 was, in military terms, a tough, experienced and well-trained force which also had its own language, a polyglot mix of words and phrases collected from decades of service around the empire, particularly in India and the Middle East. The BEF suffered terribly in the early months of the war and huge numbers of reinforcements were required. These came in the form of reserve territorials and large numbers of volunteers drawn from every county and every level of British society. Irish, Scots and Welsh mixed with Geordies, East and West countrymen and Cockneys. The men who comprised the bulk of these soldiers and sailors came from civilian backgrounds where life was unimaginably hard and society provided no support in bad times. It is a shocking statistic that one third of all the men who volunteered for service during the war were suffering to a greater or lesser extent from the effects of malnutrition. For many of those men, tough as it was, army life was an improvement on what they had left behind. They had their own regional language but as most were trained by regular army non-commissioned officers they absorbed much additional slang.

However, as a result of the unexpected introduction of trench warfare in late 1914, there arose a lingua franca that reflected not only the unique, self-deprecating humour of the British, but also their stoicism. Without doubt, a certain amount had an historic precedent, the best example being the unique form of street argot that evolved in the East End of London, known as rhyming slang. Although still debated this is thought to have begun as a means of private communication between costermongers and street sellers sometime in the early 19th century. However, a great many of the words and phrases were simply made up by the soldiers in response to the conditions in which they found themselves.

Next page