Campaign 90

Vimeiro 1808

Wellesleys first victory in the Peninsular

Ren Chartrand Illustrated by Patrice Courcelle

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

NAPOLEONS CONTINENTAL BLOCKADE

T he events which led to the battle of Vimeiro in Portugal and the British involvement in the Peninsular War had their origins far from the little town set in the rolling hills north of Lisbon. Continental Europe in 1807 was dominated by Napoleon Bonaparte, emperor of the French and one of the great military captains in world history. He had seized power in France in 1799, been crowned emperor in 1804, had defeated Austria and Russia at Ulm and Austerlitz in 1805, vanquished Prussia at Jena the following year and humbled Russia again at Friedland in 1807. This had led to the Peace of Tilsit signed in July 1807 with Alexander I, emperor of Russia, which acknowledged the new balance of power in central and eastern Europe with Napoleons creation of the kingdom of Westphalia and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw.

Of the major powers battling Napoleonic France, only Britain remained uncowed. As an island nation with flourishing world-wide trade and a great military fleet by far the worlds most powerful it retained the resources to continue the fight while remaining virtually invulnerable to invasion by Napoleons armies. In 1804 and early 1805, Napoleon had gathered an Army of England at Boulogne but to no avail. The Royal Navys iron grip on the English Channel proved unbreakable and, finally, Napoleons troops marched towards Austerlitz instead. The Royal Navy was also blockading more and more of the European coastline.

At the end of 1806, shortly after his entry to Berlin, Napoleon, now preoccupied with Britains blockade, signed decrees which put an embargo on all British trade with Europe. In effect, the Berlin Decrees declared Britain to be under a tight French-imposed blockade. Travel, trade and correspondence between Britain or its colonies and continental Europe were henceforth forbidden. Recalcitrant countries were severely punished by French troops appearing on their borders. Through this Continental System it was hoped to ruin Britain, forcing her to sue for peace and accommodations with Napoleon. But Britain could get along quite well thanks to its colonies and overseas trade links. Wood for its immense commercial and military fleets came from Canada, sugar and other tropical delicacies from the West Indies, tea and spices and many other products from India and the Far East only wine, most of which came from Portugal, seemed in jeopardy.

Nevertheless, the British retorted on 7 January 1807 with an Order in Council prohibiting trade by ships from neutral countries between two French or French-allied ports. This amounted to an attempt to totally halt Napoleonic Europes external trade and commerce; and it was an effective blockade as Britains Royal Navy was already monitoring the French and French-allied coastline. The result was that nearly every product from outside Europe, such as sugar, became increasingly scarce and expensive on the Continent.

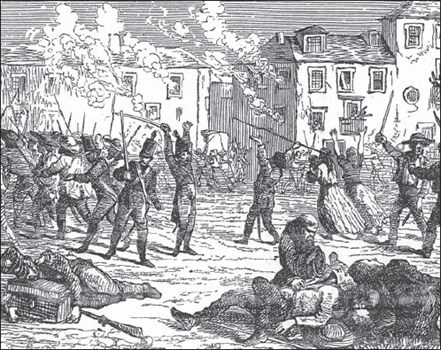

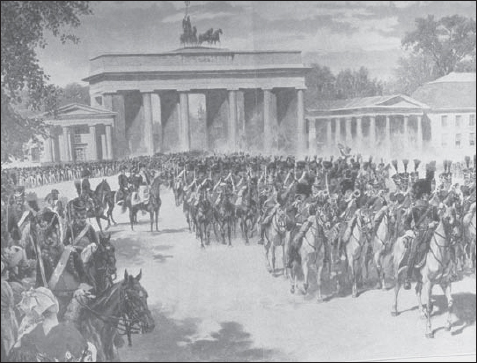

Napoleons troops enter Berlin on 27 October 1806. The following month, on 21 November, Napoleon signed the Berlin Decrees, which would lead in due course, to the invasion of Portugal a year later. (Print after F. de Myrbach)

PORTUGAL BEFORE 1807

Then there was Portugal to further exasperate Napoleon. This ancient kingdom shared the Iberian peninsula with Spain, its habitually hostile neighbour. But Portugal was and remains a very different country from Spain. From the Middle Ages, the Portuguese were drawn by the sea and, by the end of the 15th century, were the first Europeans to reach India. In the next century, they established trade links in the Far East and colonies in Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, Ceylon, India, Macao and the Spice Islands including Timor.

Defensively, geography had favoured Portugal along her frontier with Spain. The countrys northern and eastern borders have a nearly continuous chain of mountains pierced by the Douro, Tagus and Guardiana rivers which flow broadly east to west. In those wild border areas, their valleys are steep and almost impassable; in the mountain valleys the rivers flow fast like rapids and are unnavigable. Strong castles, and later mighty fortresses, were built to guard the few gaps in Portugals mountainous shield.

Over the years, Portugal whose history was largely a continuous struggle to retain her independence, first from the Moors and then from the Spanish forged alliances with England, that other maritime nation to the north. English soldiers were found in Portugal as early as 1380 and links with England became stronger as trade developed between these two seafaring nations. They were allies in most wars and avoided interfering in each others colonial expansion overseas. The old saying that Portugal was Britains oldest ally was certainly true. A Roman Catholic country, Portugal nevertheless took a largely pragmatic attitude towards her Protestant ally. In the numerous wars of the later 17th and early 18th centuries, the Portuguese were often found fighting side by side with British troops in the peninsula as well as in other parts of the world.

Maria I had been queen of Portugal since 1777 but because of her distraught condition, Prince Joao was made regent in 1799. Born in Lisbon in 1734, she died in Rio de Janeiro in 1816. Marble sculpture, Estrella Basilica in Lisbon. (Photo: RC)

The French Revolution had a profound effect on Portugal. In 1793, along with most European nations, she declared war on the French republicans. A Portuguese contingent with the Spanish army fought bravely but the French eventually broke into northern Spain and the Spaniards signed a peace treaty in 1795, then switched sides a year later. This came as no great surprise to the Portuguese who mistrusted the Spaniards more than the French anyway. The treaty with Britain, her old and trusted ally, remained. In 1797, Britain sent a corps of 6,000 men to bolster Portuguese defences. In 1798, a Portuguese Navy squadron proved such an irritant to General Bonaparte during his Egyptian expedition that he vowed revenge. All these tensions had an increasingly adverse effect on the health of Portuguese Queen Maria I. In 1799, her son became Prince Regent Joao VI, the effective ruler of Portugal.

By 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte had become First Consul and his victories over most countries on the Continent left France the most powerful nation in western Europe. Napoleon pushed his Spanish ally to attack Portugal with the help of a French corps. The resulting and halfhearted War of the Oranges, which lasted barely three weeks, demonstrated how desperately weak the Portuguese defences had become. The campaign got under way in May and Portugal, overwhelmed by three armies numbering some 60,000 men, lost the war and sued for peace, which was signed on 6 June. Portugal had to cede the border area around Olivenza to Spain and close its ports to British ships.

Britain eventually concluded the Peace of Amiens in 1802 but was again at war with France in 1803. Portugal, for its part, tried to stay more or less neutral but the pressure was mounting, especially from November 1806, when Napoleon signed his Berlin Decrees followed by the Milan Decrees of 1807. If Portugal chose to follow the French emperors policy, its economy would most likely be rapidly ruined and its colonial empire one of the keys to its prosperity occupied by the British. If it chose to defy Napoleon and continue its overseas and British trade, a French invasion was almost inevitable. Portuguese diplomats attempted to negotiate compromises with the French, but Napoleon increasingly considered Portugal an enormous and frustrating loophole in his Continental System. By the summer of 1807, Napoleon had tired of Portuguese attempts at conciliation. Troops in south-western France were provided with supplies and prepared to march south.