PENGUIN CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

Wellingtons dispatches were first published, in three volumes, between 1834 and 1839 and revised 1844

This edition, with a new introduction and editorial material, first published in Penguin Classics 2014

Selection and editorial material Charles Esdaile, 2014

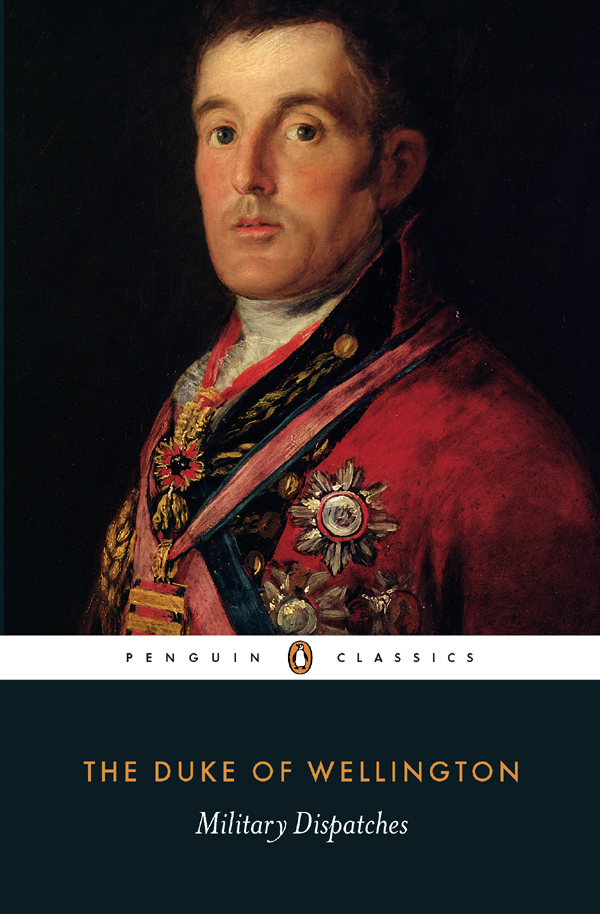

Cover: Detail from The Duke of Wellington, 181214, oil on panel, by Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes. National Gallery, London, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library

All rights reserved

The moral right of the editor has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-141-39432-9

PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

MILITARY DISPATCHES

ARTHUR WELLESLEY , Duke of Wellington (17691852), is generally viewed as Britains greatest military commander. He fought in some fifty encounters across India and Europe, with almost all battles ending in victory. He finally defeated Napoleon as commander of the Allied forces at Waterloo. He was twice British prime minister.

CHARLES ESDAILE is the author of The Peninsular War and Napoleons Wars (both published by Penguin) and is Professor in History at the University of Liverpool.

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

For Helen and Mike (quite literally!)

Preface

In some ways this is a very personal book. In 1985 I was appointed Wellington Papers Research Fellow at the University of Southampton, and the next four years I have always considered not just to be some of the happiest of my whole life, but also the real foundation of my career. As a research student working on the subject of the Spanish army in the Peninsular War, I had always been aware of the published versions of Wellingtons dispatches and had, indeed, dipped into them from time to time, but, in my ignorance, I had never considered them to be particularly important from the point of view of the Hispanist which I considered (and still consider!) myself to be. Only when I came to Southampton, then, and was initiated into the mysteries of the Wellington Archive, did I become aware of the extraordinary value that the papers held for my work, the book that eventually came out of my thesis being much enriched by what I found in them, whilst they also provided the basis for the study that I went on to write of the Duke of Wellington and the command of the Spanish army. To have been asked to edit the current work has come, therefore, as a great privilege: it is not often that a scholar has so public an opportunity to pay homage to a source that has had so formative an effect on his development as a historian.

With this sense of privilege, however, also came a sense of foreboding, for a limit of some 120,000 words is but a small compass when it comes to selecting material for publication from the 2,000,000 or more words of the published dispatches. In approaching this task I took the view, first, that at the heart of any work should lie a certain conceptual unity, and, second, that in the case of the Duke of Wellington what those who come to his correspondence for the first time probably require is an account of the military narrative. As I have tried to hint at various points, Wellingtons glory was not just that he won battles or conducted successful campaigns, but that he did so in a geographical, social, political and cultural context that was problematic in the extreme, and it is in truth in revealing this complexity that his correspondence is at its most valuable. Yet to wallow in such complexity would not be helpful for the neophyte, while the non-neophyte is likely to be all too well aware of it already, and certainly better aware of it than I can possibly make him in the pages of so slim a volume. Indeed, such would be the problems involved in deciding what to make use of and what to omit that one suspects that it would not be conducive to the good health of the current author: the original editor of Wellingtons correspondence, Colonel John Gurwood, ended his days by committing suicide whilst suffering from a state of depression induced in part by overwork. What we have here, then, is essentially a story, namely the story of Wellingtons campaigns in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe as recounted at the time by the Duke himself. For those who wish to go further, I hope that the brief section on Further Reading will provide some inspiration, whilst for anyone who has access to them, I can do no better than suggest that they turn to the original work from which the documents published in this book were lifted, J. Gurwoods The Dispatches of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington during his Various Campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the Low Countries and France from 1789 to 1815 (new and enlarged edition; twelve volumes; London, 1852).

Yet taking the decision outlined here has cost me not a little anguish. The view of the Peninsular War that is presented in these pages cannot but be a very English one and yet I have spent my entire career arguing that Anglocentric approaches to the subject are hopelessly inadequate, that the historian of the Peninsular War, indeed, has to perceive the subject from Madrid or Lisbon rather than London or even Wellingtons headquarters. Meanwhile, as I intimate above, my work on the Peninsular War has always essentially been the product of a Hispanist who identifies with Spain and the Spaniards in a manner that would have been utterly incomprehensible to Wellington: as the Duke once said of John Downie, the extraordinary Scottish adventurer who became a Spanish general, I am, I fear, Spanish down to my shirt. To edit the current work, then, has come as a very strange departure for me and one that I am not entirely comfortable with: if one reads Wellington and nothing but Wellington, it is all too easy to infer that, to paraphrase one of his more vitriolic tirades in their respect, the Spaniards never did anything, much less did anything well. Such a view is, of course, wholly unjustified, and, revisionist though I am when it comes to analysing the Spanish national myth, I would wish to dissociate myself from such a stance most completely: much of what the Spaniards did was out of view of Wellington and therefore but imperfectly reflected in his dispatches, but the fact is that many of Spains soldiers, in particular, fought with the utmost courage in the face of circumstances that even Wellington could not have overcome.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS