First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John D. Grainger 2013

9781783830794

The right of John D. Grainger to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording

or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the

Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire.

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen &

Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword

Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe

Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The

Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

The great World War of the second quarter of the twentieth century was an imperial war. The aggressors, Germany, Japan, Italy, were intent on expanding their empires; the defenders, Britain, France, Russia, the United States, aimed to keep the empires they already had.

This is, of course, not the way this series of wars is usually perceived. Freedom from tyranny is the usual viewpoint, at least among the victims of aggression. But the Indians did not see it that way, nor did the Egyptians, nor perhaps many Africans. Some of those already free took the aggressors side Finland, Romania, some of the Boers of South Africa, and other victims of earlier imperial conquests. In that connection the perception of Britain standing alone in 1940 needs to be abandoned. Britain was accompanied in its stance by an enormous empire, and had the assistance of large numbers of soldiers from European countries already squashed by the German conquest. In the scale of numbers and resources, in 1940 Germany was the weaker.

It also helps in understanding to appreciate that the Second World War encompasses a large number of separate wars, which began at different times and ended at different times. From the British point of view the war began in 1939; from that of the United States in 1941; from that of Japan in 1931, or 1937, or 1941. On war memorials in France the dates of the conflict are usually given as 1939 1940 and 1944 1945, with the resistance victims listed in between. For Italy the war began in 1940, ended in 1943, and began again at once until 1945.

And in all this there is the war between Britain and France. It is almost hidden beneath the tremendous events of the Second World War, but it was a continuing, if intermittent, conflict. Never actually declared, it was nevertheless a war between two countries which had been allies for a short time at the beginning of the overall war, and were to be on the same side at its end. In between they fought each other or rather, perhaps it would be better to say that Britain fought France.

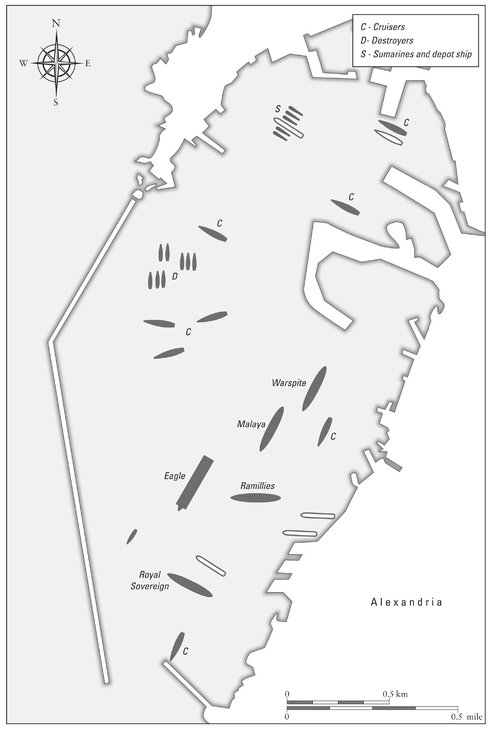

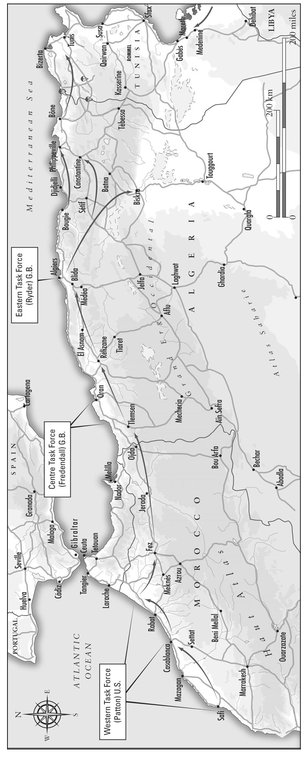

Between 1940 and 1942 Great Britain and France fought a series of conflicts in several parts of the world; Europe, Africa, the Mediterranean, even America, which in total added up, by 1942, to the destruction of the French overseas empire an outcome in which the British were, ironically, assisted by the Germans, the Japanese, and the United States. Usually, amid the din of even greater events at sea, in Russia, in the Pacific, this conflict is too often more or less hidden away, though at times it surfaced to have an effect on the wider war; it is a series of events rather like rocks in the path of a steamship, appearing suddenly and sometimes unexpectedly in its path.

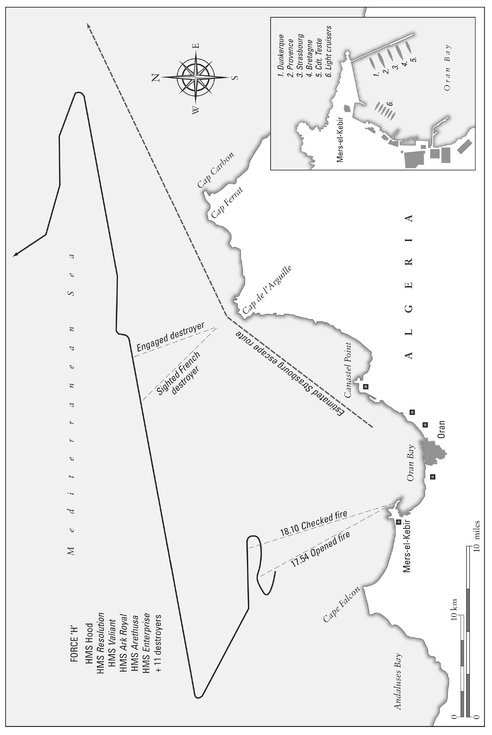

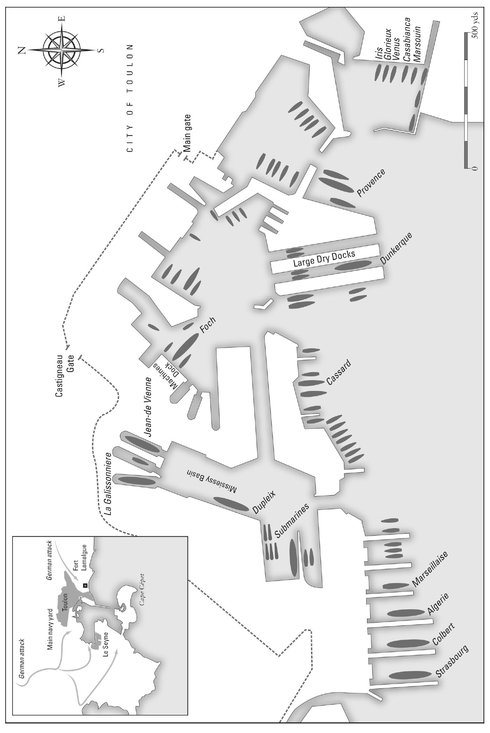

It has a wider significance, however. The restraint of the Vichy French government was quite remarkable under the stress of British attacks, and failure of the German government to appreciate their opportunity was no less surprising. Had the Vichy government declared war in 1940, after the events at Mers el-Kebir, the British position, in the Mediterranean and in the English Channel, would have been grave indeed. The prospect of dozens of French super-destroyers and destroyers assisting the Germans in the invasion of Britain is one which chills the blood. Beyond that, and back in the area of reality rather than supposition, the speed of the collapse of the French Empire should have been a clear sign to the British of the fragility of their own empire, which in fact lasted only a couple of years beyond the end of the wider war. There is no sign, however, that the lesson was taken on board, perhaps because the mindset of the British simply assumed the solidity and permanence of their empire.

Because France had been defeated in 1940 while Britain, also defeated, had survived in embattled freedom, the conflict was essentially one which was generated in and by Britain; that is, the aggression was almost always from the British side. It was conducted with very mixed emotions, ranging from the agony of the British naval officers who had to order the fleet to fire on French ships at Mers el-Kebir to the cheers which greeted the Prime Ministers announcement of that action from the MPs in the House of Commons. Later these emotions were more hidden, partly because later British attacks had a more obvious justification than Mers el-Kebir, but there was always a manifest British reluctance to be really ruthless and a constant wish to persuade the French to come to their senses, abandon their hostility to the British, and join in the war with Germany and Japan.