First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Pen & Sword Maritime

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John D. Grainger 2011

ISBN 978-1-84884-161-1

ePub ISBN: 9781844684380

PRC ISBN: 9781844684397

The right of John D. Grainger to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by MPG Books Group

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History,

Pen and Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Maps and Illustrations

Illustrations

All images are from the authors collection.

Maps

Map 1: The Ptolemaic Empire and the Eastern Mediterranean.

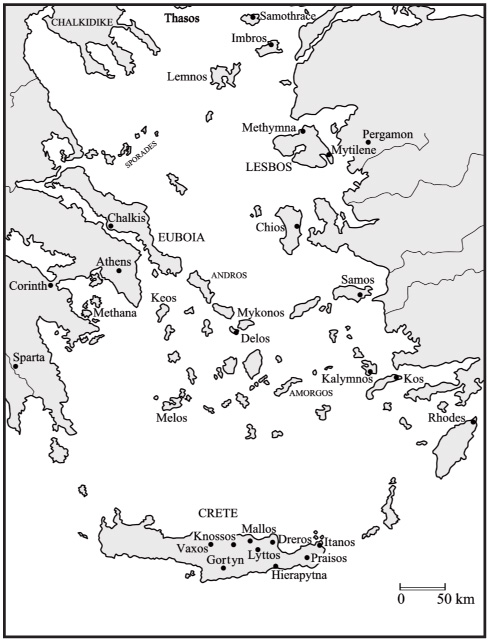

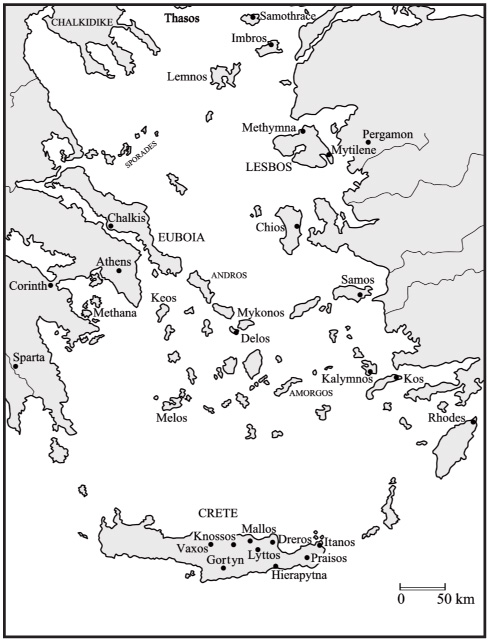

Map 2: The Aegean Sea.

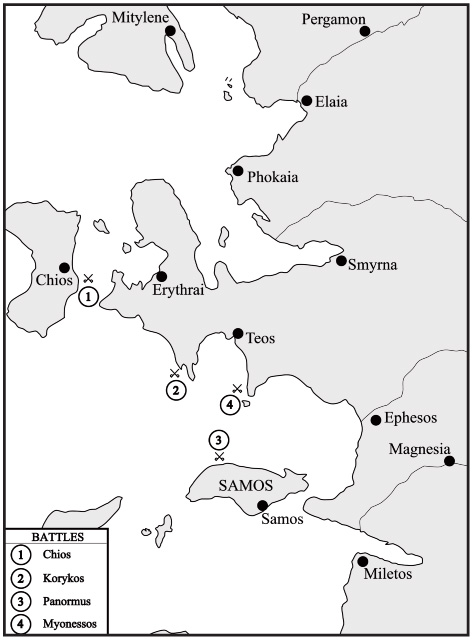

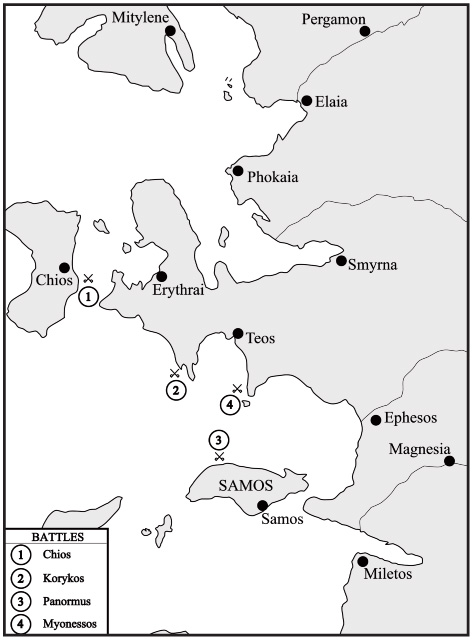

Map 3: Ionia-Aeolis The Battle Zone.

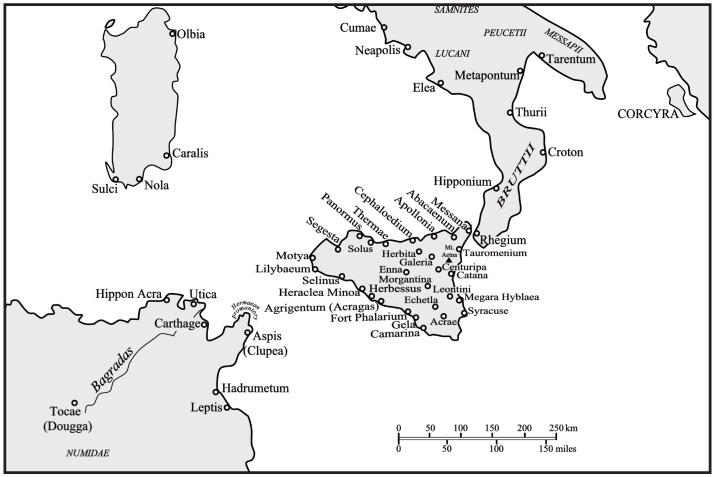

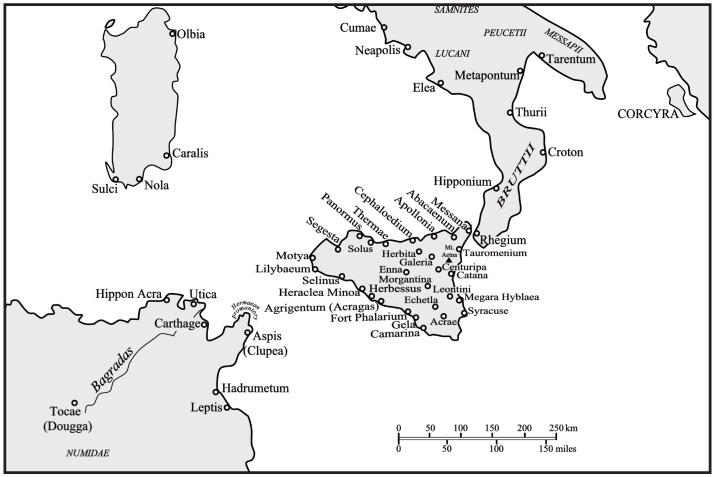

Map 4: Sicily and its Neighbours.

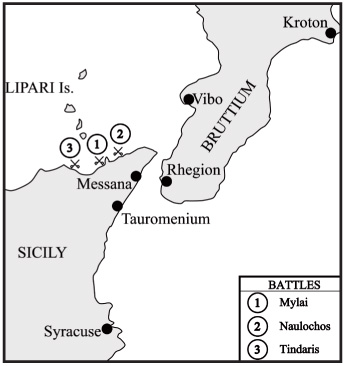

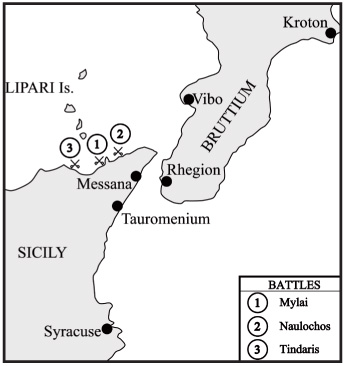

Map 5: The Strait of Messina.

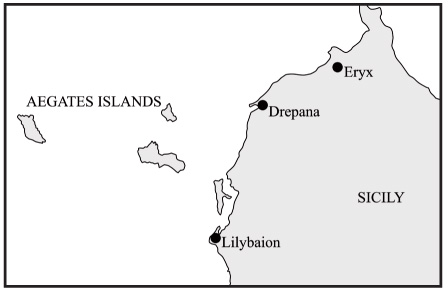

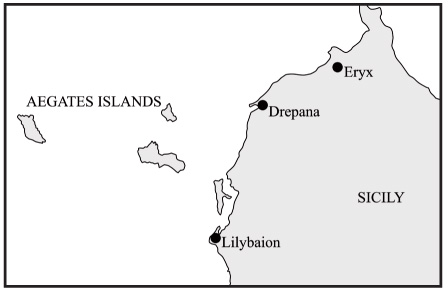

Map 6: Western Sicily.

The Great Harbours (Maps 7A, 7B and 7C)

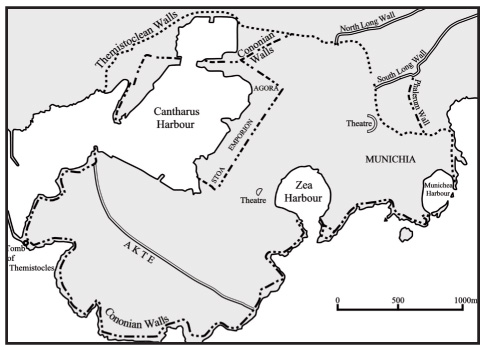

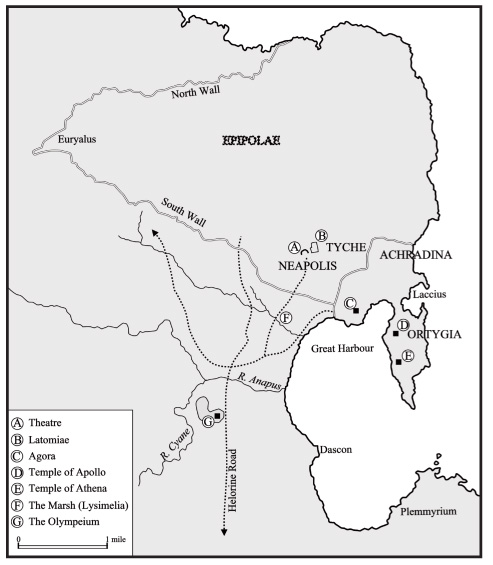

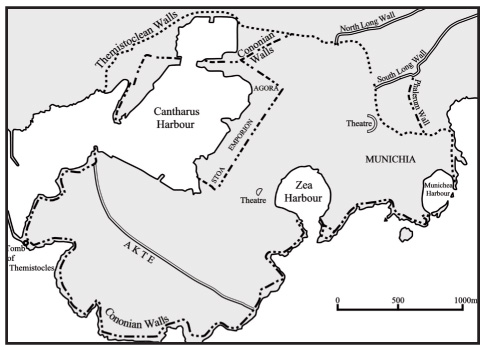

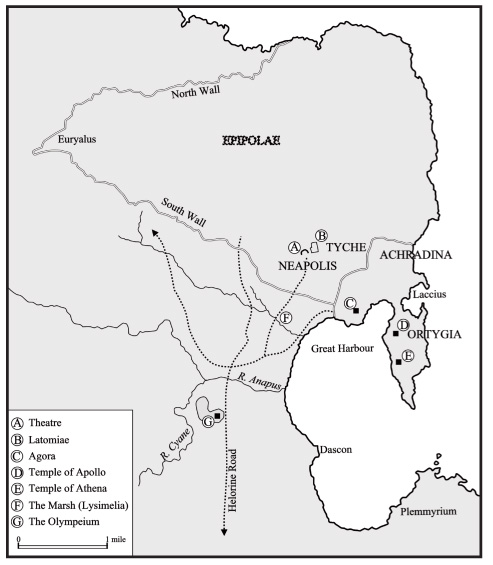

In the Hellenistic world there were four particularly notable harbours. The original in many ways was Peiraios, the port of Athens () was similarly natural, where the island Ortygia separated the main harbour from the smaller naval harbour (Laccius). Ortygia had been an island, so originally there was a clear communication between the two.

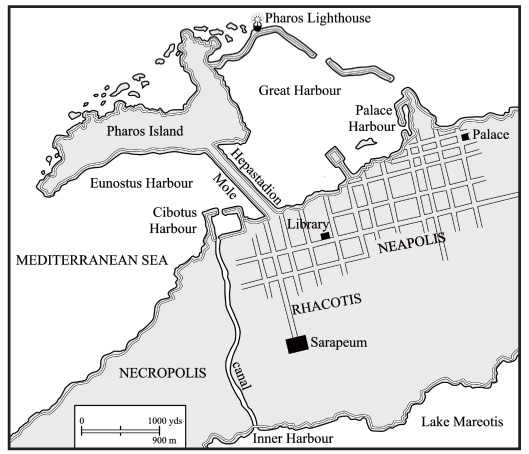

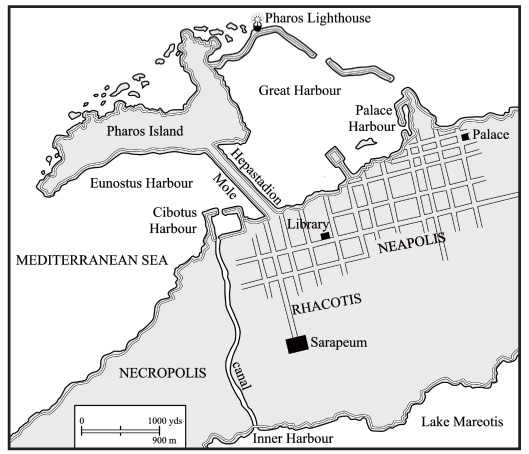

The other two great ports were artificial. Carthage (see plate xx) was excavated from the mud of the shore. There was a rectangular commercial harbour, with long wharves for unloading ships lying lengthwise to the quay, and a circular naval harbour which had an administrative island in the centre. Each harbour had a separate entrance from the sea. Alexandria (), laid out in the last years of Alexander and the beginning of the rule of Ptolemy I, was built along with the city, and made use of the island of Pharos. This was connected to the mainland by a mole, so forming two harbours. Each of these had a section which was official for the Palace and the Kibotos harbour and there was a third harbour on the shore of Lake Mareotis, connecting with the River Nile, along which came the supplies for the city.

Map 7a: Athens.

Map 7b: Syracuse.

Map 7c: Alexandria.

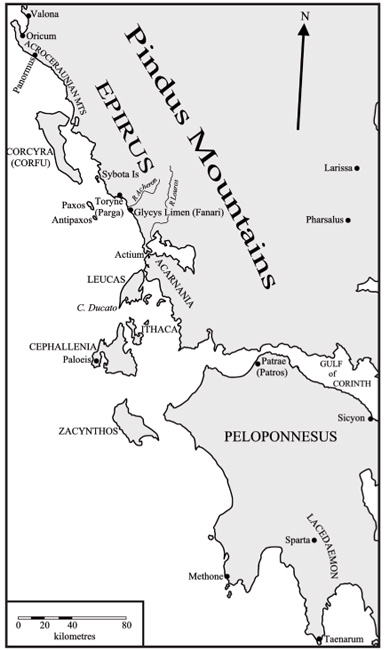

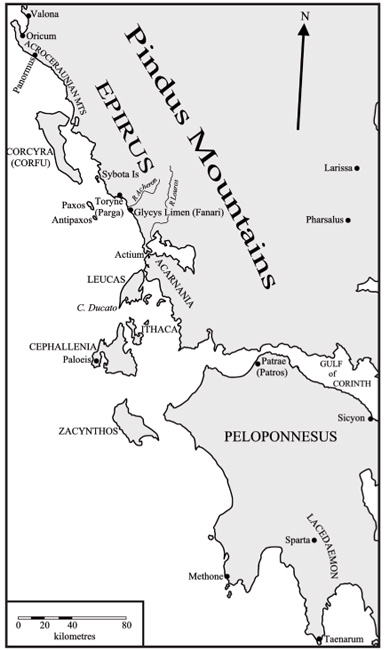

Map 8: Greece West Coast.

Map 9: Actium.

Introduction

Between the expeditions of Alexander into the Persian Empire starting in 334 BC and that of Octavian (later to be Augustus) to Egypt in 30 BC, the Mediterranean was repeatedly the scene of major warfare at sea. This was not a new thing, of course, since several cities and states around the Middle Sea had indulged in war at sea in the past, but in the Hellenistic period it occurred more frequently, over a wider range, and with greater intensity than before or than at any time afterwards until the great wars of the sixteenth century AD.

This was a period which saw several states deliberately building up navies to serve as major instruments of power. There was competitive pressure on all seastates to build more, bigger, and better ships a naval arms race the like of which was perhaps not seen until the early years of the twentieth century AD. The competition involved not just building and crewing more ships than any rival, but also innovations in size of ships, and in the technique, tactics, and strategy of war. Different methods of naval warfare developed and were tested in battle, and navies were deliberately used to impress and intimidate potential allies and enemies.

Such competition was expensive, not only in the building of ships and in paying and feeding their crews, but also in constructing shore installations. Harbours large and safe enough to hold great fleets had to be built and facilities to hold supplies of naval tackle ready to build new ships and repair those damaged had to be gathered and stored. Ships had to be maintained and repaired and replaced once they wore out or became rotten. And in battle a sunken ship took with it not only the investment made in its construction and use, but usually most of its crew as well.

Lost battles at sea were capable of stopping an advancing empire in its tracks. Victories at sea persuaded men to declare themselves kings. The acquisition of power at sea was one of the major elements in the overall political contest in the Mediterranean world, which involved half a dozen great powers and dozens of small ones. This contest was won in the end by Rome, of course, by the early years of the second century BC, and it was by the use of sea power that Rome prevailed. This is in a sense paradoxical, since Rome is generally regarded above all as a successful land power the legions, and so on. Nevertheless it was only by the use of its naval power that Rome won its wars. Think of Italys geographical situation: only by sea could a Roman force reach any of its enemies.

Sea power in the Hellenistic period, therefore, is at the heart of the political conflicts of the time. It is perhaps an even greater element in the success or otherwise of the various states in that context than any other aspect of power. Its creation, with its ships, harbours, and crews, was a central part of the development of the power of the state in that time as well, and the expenditure involved was a major element in taxation and finance, in the employment of artisans, and so in economic development generally. The end result was the overwhelming state power of the Roman Empire, control of which was won by Octavian/Augustus in a sea battle. After his victory at Actium most of the navy was dismantled. With no enemy at sea, a navy became an expensive and unnecessary luxury.

Next page