First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John D. Grainger 2015

ISBN: 978 1 78303 050 7

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 450 5

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 462 8

The right of John D. Grainger to be identified as the Author of this

Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family

History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select,

Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper,

Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

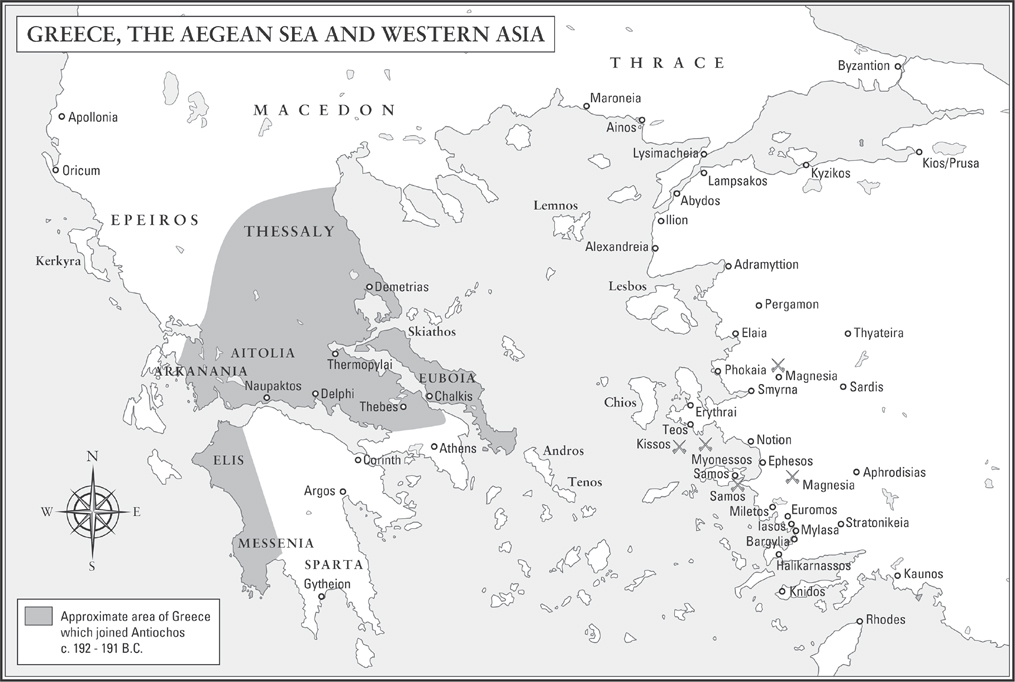

Maps

Introduction

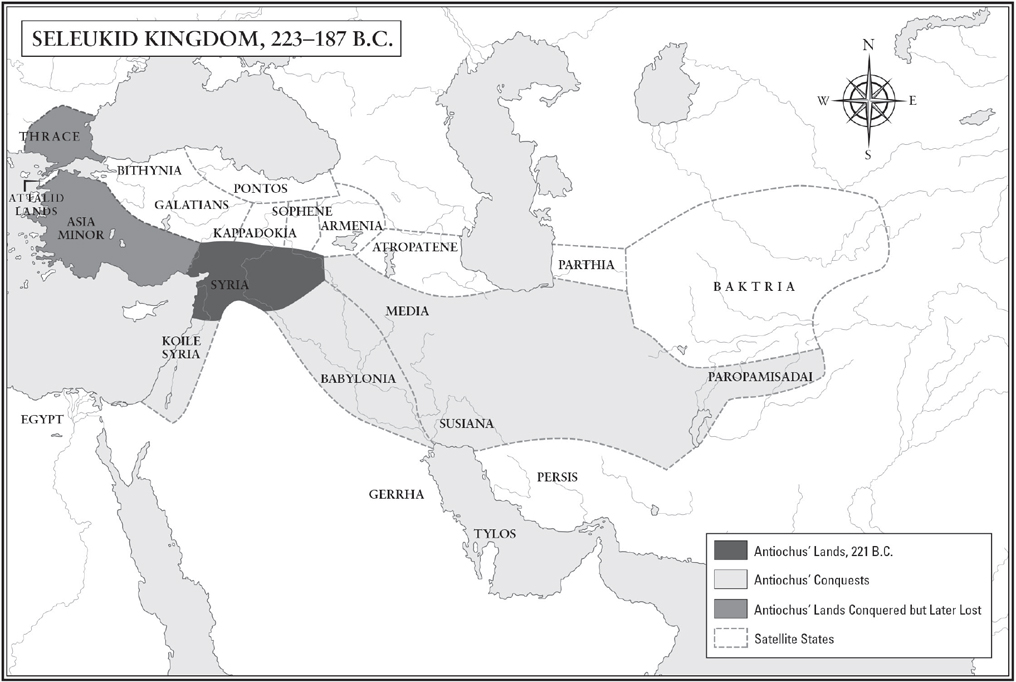

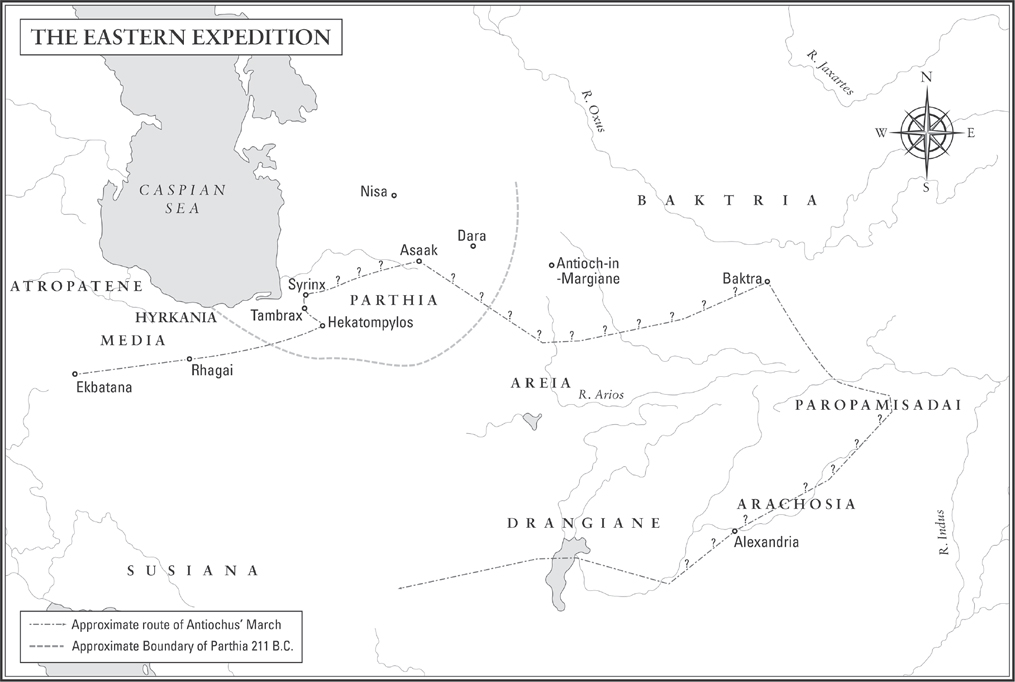

T his is the second of three books, collectively describing the history of the Seleukid Empire from the time of Alexander the Great and its final extinction by a casual word from Pompeius Magnus. This volume deals with the reign of just one of the dynastys kings, Antiochos III, another who has been given, or in his case had taken, the title of great. He reigned for thirty-five years, longer than any other member of the family, and since his reign was chronicled by the historians Polybios and Livy, we know much more about his work than we do of almost any other of the kings. He was also in effect the second, or perhaps the third, founder of the empire.

The Seleukid state was a rickety structure, which was always liable to break down, or to shed the occasional province, or both of these. The crucial moments in its history were always at the death of the kings. The original founder, Seleukos I, had cobbled his kingdom together province by province through a career lasting three decades, but had not been able or had time to integrate the whole properly, and it went through a civil war when he died. His son, Antiochos I, put the kingdom back together, and defended it from attacks by Galatian invaders in Asia Minor and Ptolemaic enemies in Syria, but it collapsed again in 246 BC when his son Antiochos II died, leaving a disputed succession between three of his sons. This time putting the kingdom back together took much longer, and the breakdown continued for twenty years. When Antiochos III unexpectedly inherited the kingship he was king of only the central regions of Syria and Babylonia. The rest had broken away.

So Antiochos work was to put his inheritance back together. Had he died in the first ten years of his reign it is very likely that the kingdom would have disintegrated into competing fragments. In fact he had a very successful career in restoring the kingdom of his ancestors, and made some attempt at devising ways of holding it together. So just as Antiochos I had revived his fathers kingdom in the 270s BC, Antiochos III did so after 222 he was thus the third founder.

This was not an easy task. He suffered major defeats in two of the greatest battles of the Hellenistic age, yet he recovered after each one, and turned to other tasks. He died in the course of yet another attempt at recovery, and handed on a united and well-governed kingdom to his son, one which was larger than that which he had inherited.

It is very difficult to gain a sense of the mans character through the sources for his life which remain to us, but it is clear that persistence and determination were prime elements in it. His work ensured that the kingdom he ruled lasted, if in a slow and erratic decline, for another century. It is an achievement that deserves respect, more than it has been accorded, and certainly more than the ancient historians (and the moderns), hypnotized as they are by the growth of the Roman Empire, have done.

Chapter One

The New Kings Survival

W ithin a little over four years (227222 BC) the male members of the family of Antiochos III were reduced from four to one, and the last one, Antiochos himself, was only 20 years of age at his accession. In June 227 his uncle Antiochos Hierax, who had for nearly two decades ruled all or part of Asia Minor, either as governor or as a rebel king, was murdered in flight after escaping from imprisonment.

This last event brought Antiochos to his brothers throne, wholly unexpectedly and pitifully unprepared. So unprepared was he, indeed, that he was in the interior, probably Babylon or Seleukeia-on-the-Tigris, when his brother died, two or three weeks of travel away from the real centre of the kingdom, which was in northern Syria. It was perhaps a reassurance that there were in post a group of capable men, as governors of provinces or as ministers of the former king, who proved to be fully capable of governing on the new kings behalf. However, their capability was such that they rapidly developed ambitions of their own, and only one life, that of Antiochos himself, stood in their way.

The group which dominated Antiochos first years as king was headed by Hermeias, the first minister of Seleukos III, a native of Karia in southwest Asia Minor. We know little of his earlier life, but he had probably been an active official of the Seleukid dynasty for a considerable time. He it was who held the central government together in the immediate aftermath of the death of Seleukos III, and he may well have had the same role in the emergency of the sudden death of Seleukos II three years before. He certainly showed great ability, but, as with all men in such a position he was quasi-regent he faced even greater problems in internal affairs than he did in foreign.

The interpretation I give here is based on the notion that Hermeias, being the dead kings minister, was already in control when the king died,

One of his competitors was Akhaios, whose claim for access to power was his relationship to the young king. He was the grandson of the first Akhaios, a notable landowner in Asia Minor, who had been favoured by the founder of the dynasty, Seleukos I, with gifts of land once that area had been conquered. He certainly married his family into royalty: his daughter was the first wife of Antiochos II, and another daughter married a member of the Attalid family of Pergamon and was the mother of King Attalos I. His granddaughter Laodike (daughter of his son Andromachos), married Seleukos II, and so she was the mother of Antiochos III. Akhaios the younger was therefore Antiochos maternal uncle and his nearest male relative. As such he was clearly entitled to be part of the kings council.

Next page