First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

Pen & Sword History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright John D. Grainger 2014

ISBN 978 1 78303 053 8

eISBN 9781473840027

The right of John D. Grainger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon,

CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family

History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select,

Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper,

Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Maps and Tables

Maps

Tables

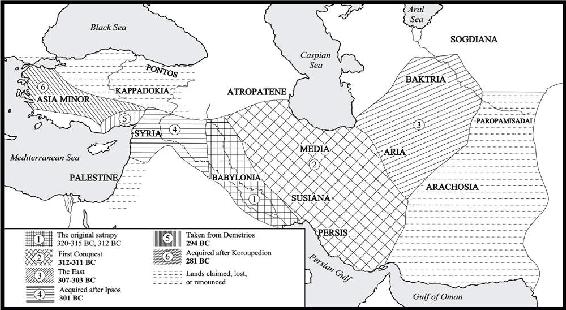

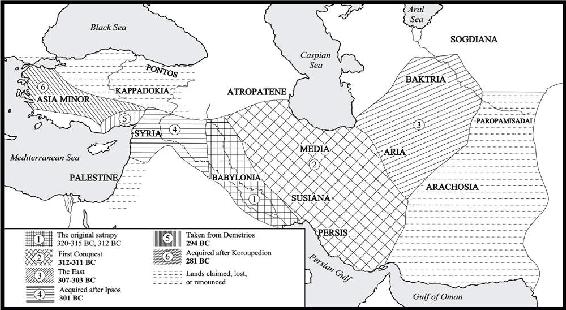

Map 1 : The Growth of Seleukos Kingdom.

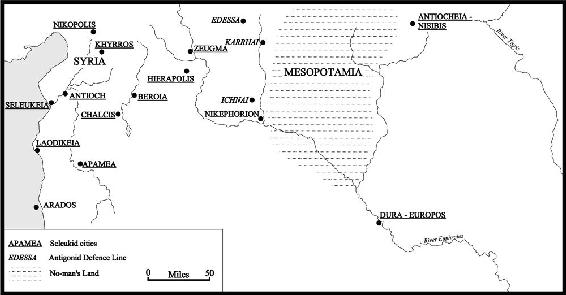

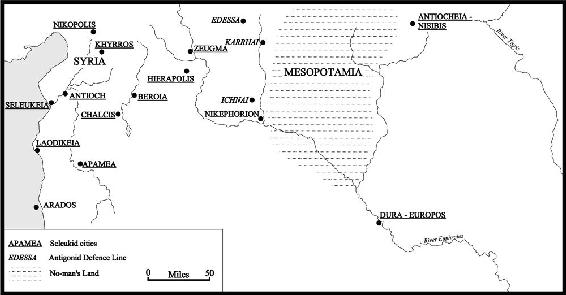

Map 2 : Syria and Mesopotamia.

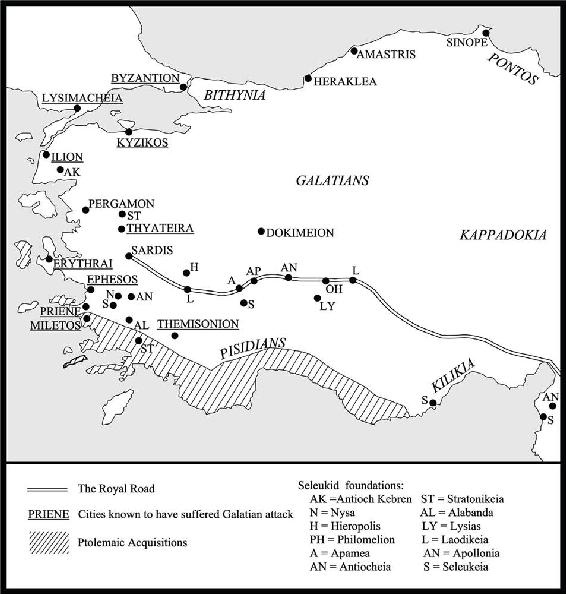

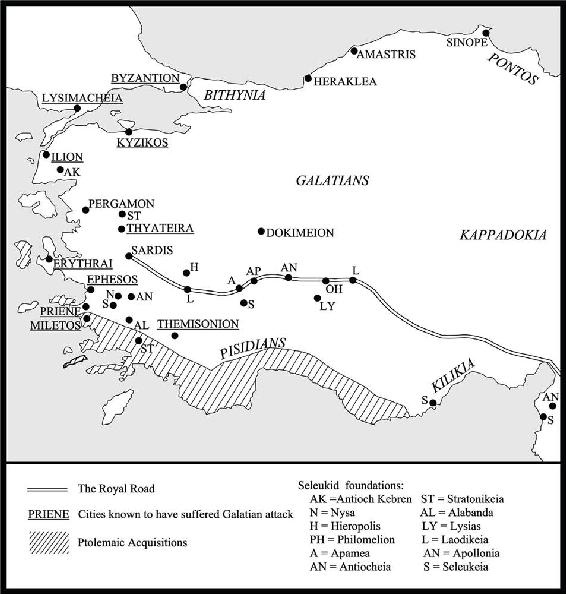

Map 3 : Asia Minor c.275.

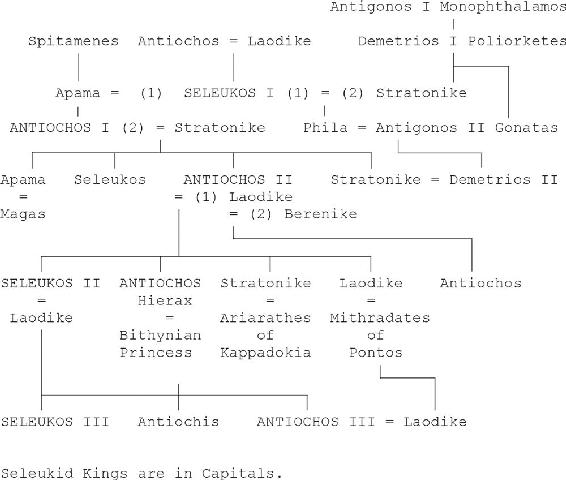

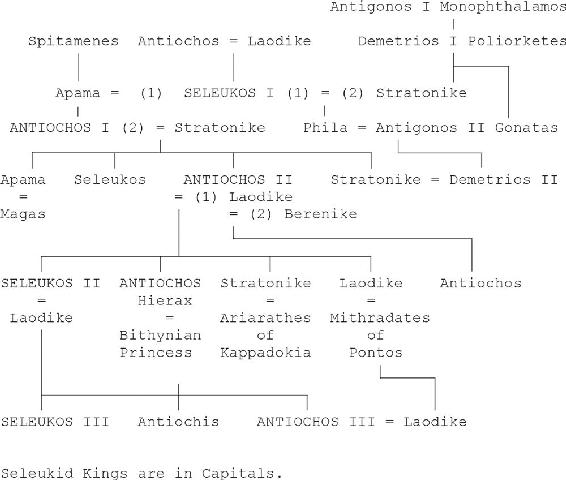

Table A: The Seleukid Dynasty

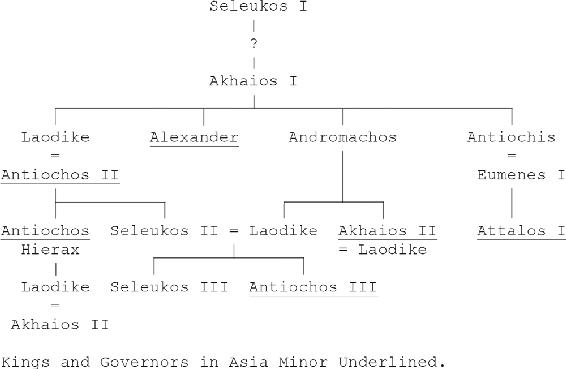

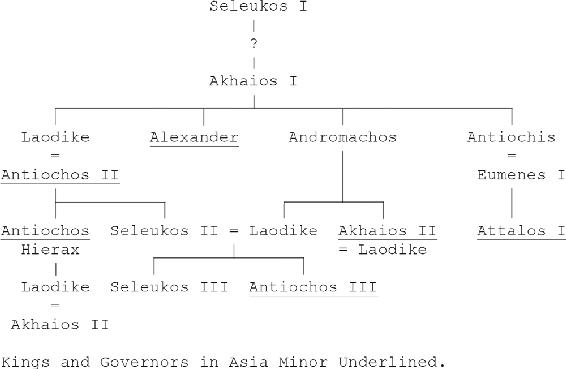

Table B: The family of Akhaios

Introduction

T he Seleukid kingdom, actually an empire, was the largest state in the ancient world for a century and a half. In that time it had more than its fair share of vicissitudes. It was built up from fragments of the empire of Alexander the Great by one man over a period of thirty years. In the next two centuries (for it lasted two generations beyond its reduction to minor power status), it collapsed twice. From the first collapse it recovered, though detached sections remained independent; the second collapse reduced it to little more than Syria. It was in that final agonizing stage that Rome met it, with the consequence that ever after the kings have been referred to as Syrian. Among the Romans this was a derogatory term, and this has helped reduce the reputation of the kings and that kingdom.

Another reason for the comparative neglect of the kingdom is the general inadequacy of the historical sources, which is a recurrent refrain in this account. This is partly the result of the geography of the state, since beyond the eastern boundary of the later Roman Empire the ancient historians showed little interest, and the alternatives to their written accounts archaeology and inscriptions have not been very productive. Among those written accounts there is not one which takes the kingdom, or any of the kings, as a subject. The story must therefore be pieced together from fragments and later allusions.

The geographical range of the kings, however, was much greater than simply Syria, even if Syria was a crucial part of the kingdom. At its greatest the empire abutted on India in the east and reached into the southeastern part of Europe in the west. It existed because, as its name implies, it was ruled by kings descended from the founder, Seleukos I Nikator, and its collapses coincided with genetic failures of the royal family. The male representatives of the dynasty were twice reduced to one man only. In other words, the central element in the empire was the royal family, everything operated through and around the kings, and when the dynasty finally failed, so did the empire. Ancient accounts of the kingdom are non-existent, and perhaps never did exist. Modern accounts are almost as few. Two comprehensive treatments, one in French and one in English, date from the first part of the twentieth century, and a revisionist examination from 1993.

This is the first in a set of three books, each dealing with a section of the empires history. The first will cover the origin of the kingdom until its first serious breakdown; the second, largely because the sources are much better than for the other parts, deals only with the reign of Antiochos III (222187 BC), who, after the founder, was the most capable and longest ruling of the kings; the third volume covers the empires last century, as it fell into collapse, fragmentation, and futility.

The legacy of its existence was, however, by no means a matter of futility. When Seleukos built his kingdom it was poor, even the richest areas were failing, having been subject to the neglect of previous rulers for several centuries and then seriously damaged by twenty years of the military campaigns by Alexander and his combative successors, a practice which involved looting, heavy taxation, and destruction. This changed during the rule of these kings so that when Rome took over the last Syrian fragment it found it had acquired perhaps the most enterprising, urbanized region in the Mediterranean area. This was the true legacy of the Seleukid kingdom, a set of wealthy and enterprising cities, and a vigorous peasantry. They remained rich and enterprising until destroyed in the Crusader Wars a thousand years later.

Further, the kingdom, as it declined, gave birth to a long series of other states, from Baktria and the Greek kingdoms in India to the Pergamene Attalid kingdom in Asia Minor and the curious Judaean kingdom of the Maccabees. All of these inherited the ethos and the government system of the Seleukids, whose inheritance, therefore, continued to operate throughout the Middle East and Central Asia as long as it did in Syria. These fragments of the empire will also be part of the story.

Chapter One

The Collapse of Alexanders Empire

T he empire conquered with such speed by Alexander the Great in his campaigns against the empire of the Akhaimenid Great King, crumbled into fragments almost as soon as he was dead. In part this was due to his premature death at the age of 32, before he had time to devise a proper administrative system for his conquests. But it seems unlikely that he would have bothered to do that even if he had lived. As he lay dying he was still planning an expedition to sail round Arabia to get to Egypt. He must have known that a prolonged absence on such an expedition would produce rebellions and corruption and oppression in the empire, for this is what had already happened while he was marching through the desert from India.

Such administration as existed was a relic of the system of the Akhaimenids, with aristocratic Macedonians largely, but not completely, replacing aristocratic Persians as satraps, the governors of huge provinces. These men had their own armed forces, since there was a good deal of local opposition to the Macedonians, not to mention continuing banditry in the mountainous regions. This meant that the satraps were largely independent and could, and often did, refuse to pay any attention to instructions from the king. On his return from India, Alexander had dealt with some of the worst cases by execution, but this would not be much of a threat when he was off a-voyaging and a-conquering elsewhere. (And after reaching Egypt he planned expeditions throughout the Mediterranean, which would take several years at the minimum.)

Next page