IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF

ALEXANDER

THE KING WHO CONQUERED THE ANCIENT WORLD

MILES DOLEAC

This digital edition first published in 2015

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

London N1 9PF

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Appstore: itunes.com/apps/amberbooksltd

Facebook: www.facebook.com/amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright 2015 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-186-2

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge.

All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

I n 336 BCE, Philip II of Macedon, the man Greek historian Diodorus Siculus called the greatest of the kings in Europe, was assassinated, ostensibly by internal enemies, having united the ever-belligerent Greek city-states (with the exception of Sparta) under his leadership. He was preparing to undertake a bold war on Achaemenid Persia, to avenge at long last the sacrilege that Xerxes (r. 486465 BCE) had wrought upon the Greeks and their temples a century and a half earlier (Diodorus XVI.95.1). The League of Corinth, the coalition of allied Greek powers, had conferred upon Philip the title of strategos (supreme commander) and given him unlimited power to lead an invasion of Asia and Persias mighty empire. But, when Philip fell under the blade of Pausanias, a member of his own royal bodyguard, in the autumn of 336, leadership of the impending Persian campaign passed to his 20-year-old son, Alexander, and the course of Western history was likely changed significantly as a result.

The young Alexander was no novice on the battlefield. He had commanded Philips left flank at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE at which the Macedonians (and their Thessalian allies) defeated an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes to become the effective masters of Greece. Alexander was said to have broken the lines of the Theban Sacred Band. Numbering around 300, the Sacred Band was made up of pairs of male lovers, bound together by personal affection, loyalty to one another and the honour of their city-state. They had defeated the mighty Spartans decisively at Leuctra in 371, but they were no match for the then 18-year-old Alexander, who seemed to possess an uncanny, natural gift for finding the precise moment and place to launch a decisive assault against the enemy. Even at this early stage in his career, he led his troops personally; he took exactly the same risks that he asked of them.

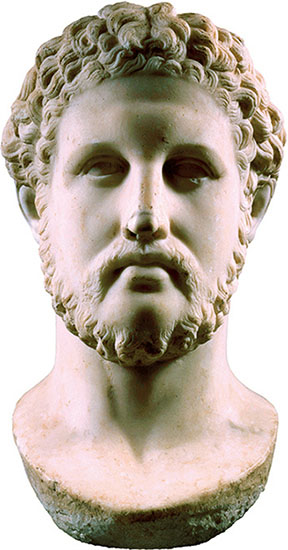

Bust of Philip II, King of Macedon (r. 359336 BCE), father of Alexander.

A Wealthy Kingdom

But the story of Alexander begins before Chaeronea. It begins in and with Macedon, the fertile, timber-rich region north of Thessaly (and the Greek city-states), into which flows the Haliacmon and Axios rivers. The political boundaries of the kingdom of Macedon that is the Macedonian state that, ruled by Philips Argead Dynasty, came to dominate first the Balkans and, thereafter, the Greek city-states to the south shifted throughout antiquity, but, topographically, the area under control of the Macedonians was a roughly uniform circuit of mountainous highlands that enclosed river basins and fertile plains. By the standards of central and southern Greece, Macedon was a land replete with natural resources. Generous rainfall coupled with flowing rivers, abundant timber forests and significant reserves of precious metals helped not only to make Macedon independent and self-sustaining, but made the Macedonian kings desirable, even necessary, trading partners for the Greek city-states. The Athenians, in particular, needed Macedonian timber to construct the triremes that would become so critical to the Greek defence against Persia in the early fifth century BCE and to the rise of Athens naval-based empire in the latter. The wily Perdiccas II (r. 448413 BCE), king of Macedon during much of the Peloponnesian War, had managed, by alternating alliances with Athens and Sparta, to guarantee Athenian dependence on Macedonian timber along with a nearly unending influx of Athenian silver in exchange for it. Philip IIs expansion of Macedons political boundaries in 356 BCE brought the rich veins of silver and gold from the mines of Mt. Pangaeum into the Macedonian orbit, providing yet another boost to the kingdoms already robust royal economy. The ornately-adorned Macedonian royal tombs unearthed at Vergina (ancient Aegae, Macedons first royal capital) provide indisputable evidence that the kings of Macedon had become very rich indeed in the course of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. At the height of his powers, in the greater Mediterranean world, Philips wealth would have been matched only by that of the Great King of Persia. It was the Macedonian royal houses significant wealth and resources that allowed the kings to engage in a delicately non-committal, diplomatic dance with Greeces main warring powers Athens, Sparta and Thebes for nearly a century and a half as they weakened one another to Macedons ultimate benefit.

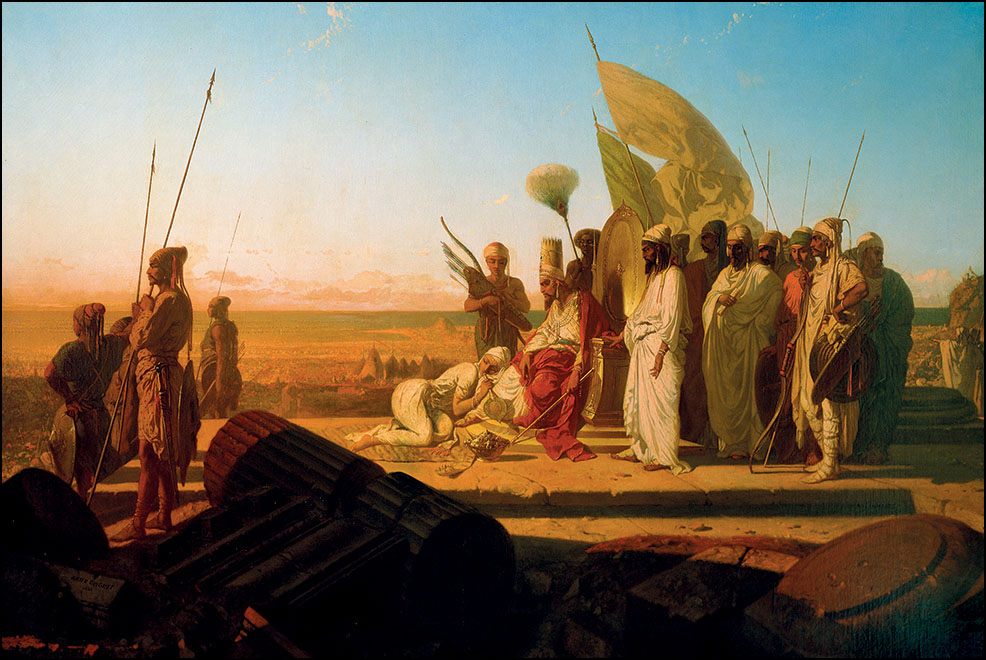

Xerxes at the Hellespont by Jean Adrien Guignet. Xerxes set out in 480 BCE with a fleet and army which Herodotus estimated was roughly one million strong.

Gold larnax or small coffin designed to hold human remains (either cremated or bent into position). This elaborately-ornamented larnax was unearthed at Vergina (in ancient Macedon) and may have contained the remains of Philip II himself. It bears a decorative sun, possibly a symbol of Philips Argead Dynasty or a nod to Zeus-Helios, master of Olympus and god of the firmament.

Greeks or Non-Greeks?

Scholars have long sought in vain to answer definitively the question of whether or not the Macedonians can properly be characterized as Greek. Were they a tribal people akin to the Dorians who migrated into and settled on the Greek mainland in perhaps the twelfth century BCE, the future Macedonians choosing instead to remain in the highland regions of the extreme north? Were they an indigenous Balkan people more closely related to the neighbouring Illyrians and Thracians? Could their ancestors have been wandering Mycenaeans, Homeric Agamemnons displaced by the Dorians and settling, bent but not broken, in the timber-laden north in the hopes of regaining their footing there? The history of early Macedon is shadowy indeed. All of the above remain mere hypotheses, intelligent guesses, but guesses nonetheless. There is such scant evidence of the Macedonians original language that it is, in fact, impossible to say with any certainty what Macedonian ethnicity was. Furthermore, early Macedons archaeological record (c. 1200650 BCE) is so spotty that definitive evidence of even permanent settlement has not yet been found and precious early tomb finds are devoid of inscriptions that could reveal whether the Macedonians were using a language separate from Greek.