Campaign 7

Alexander 334323 BC

Conquest of the Persian Empire

John Warry

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

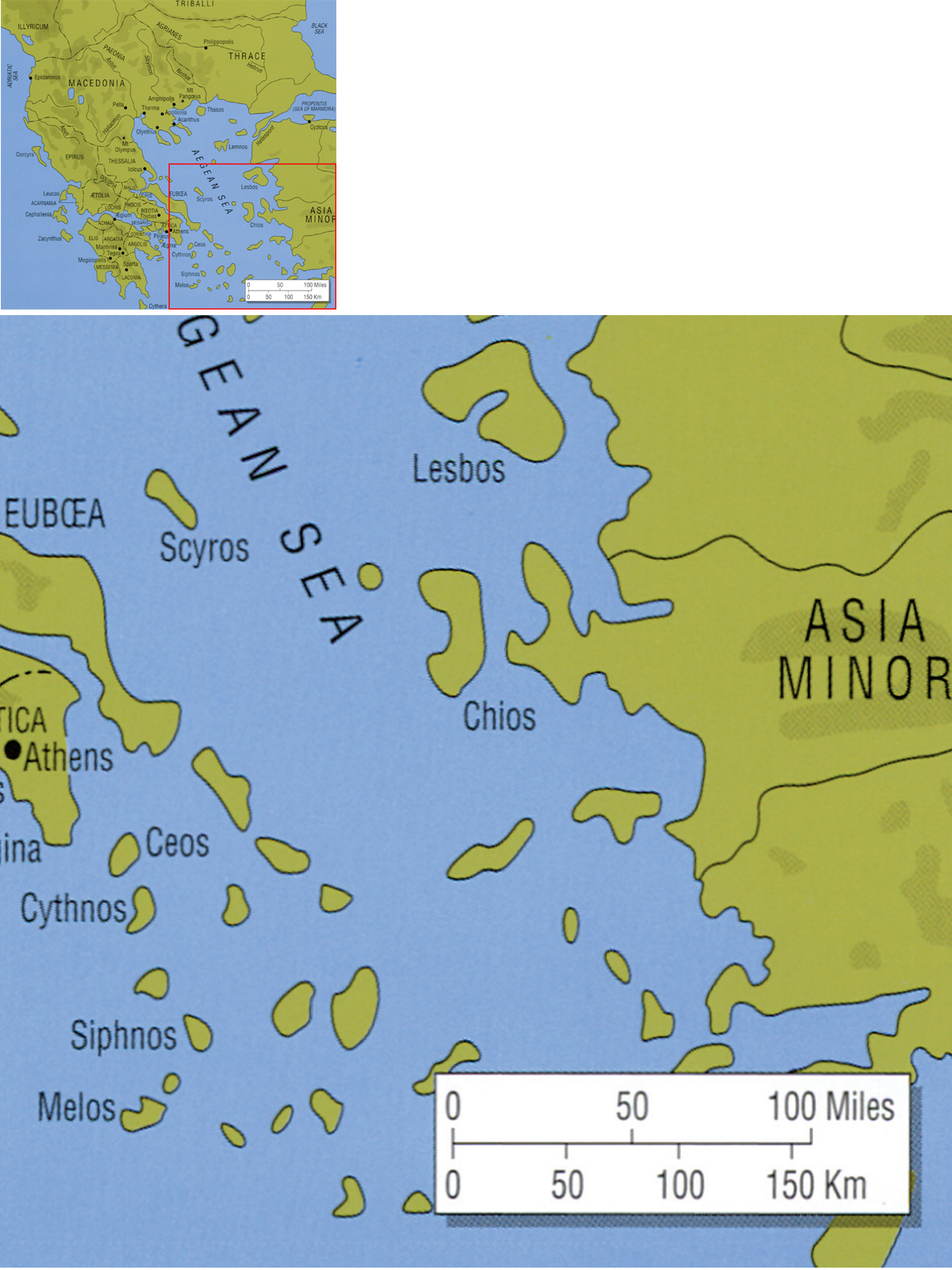

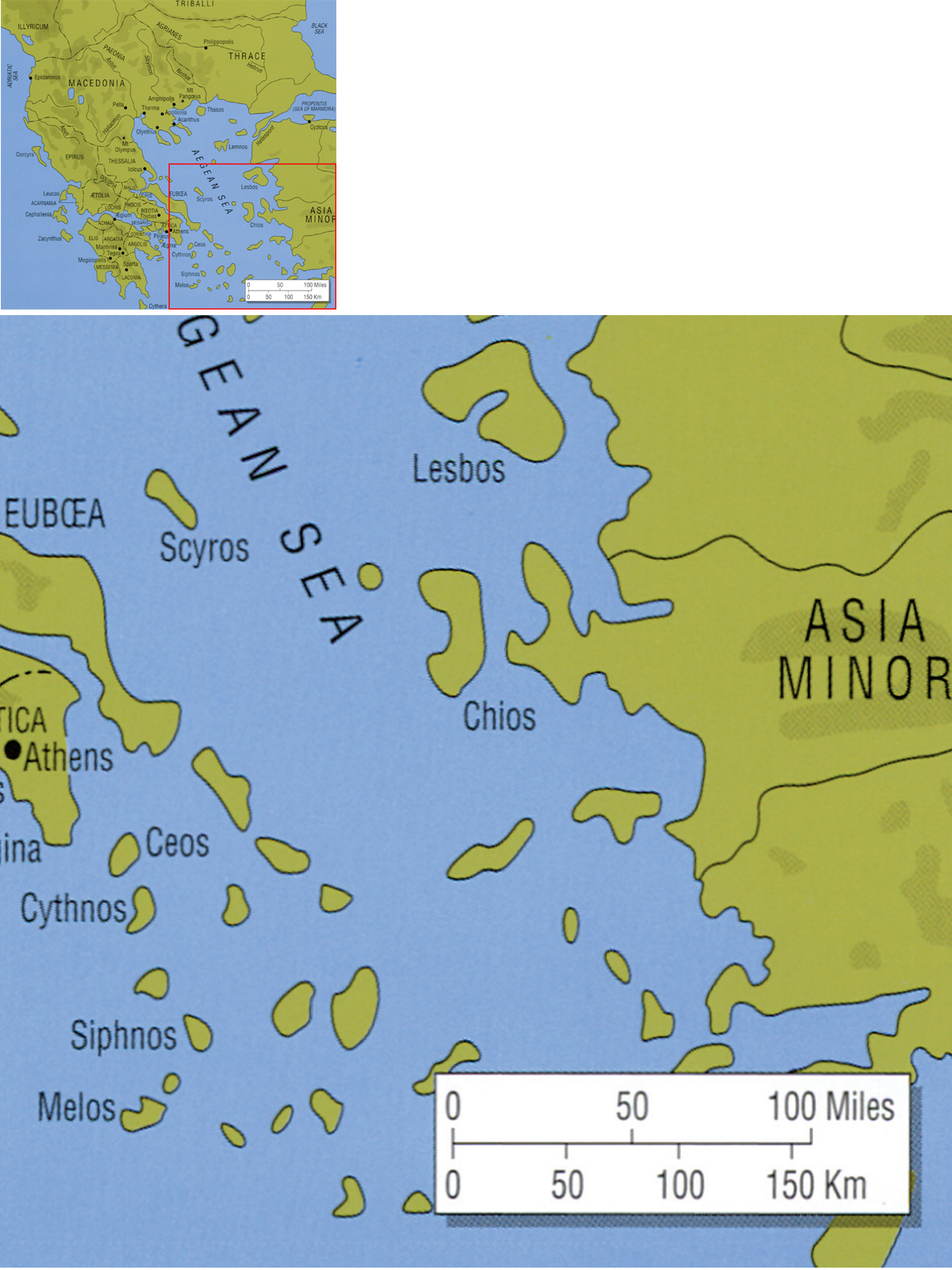

PERSIA, GREECE AND MACEDON

To understand the place of Alexander the Great in history, it is necessary to consider briefly the course of events that had determined Greek relations with Persia during the previous century and a half. The Greek cities of the Asiatic Aegean coast had been loosely subject to the Lydian kings of Sardis, until Lydia itself was overwhelmed by the meteoric rise of Persia as an imperial power. The Persians, like the Lydians, were on the whole mild masters. Only in 499BC did the Greek cities of the coast rebel, and when they received help from the Greek mainland, the Persian kings, Darius and Xerxes, launched two unsuccessful punitive expeditions against Greece in 490 and 480BC respectively.

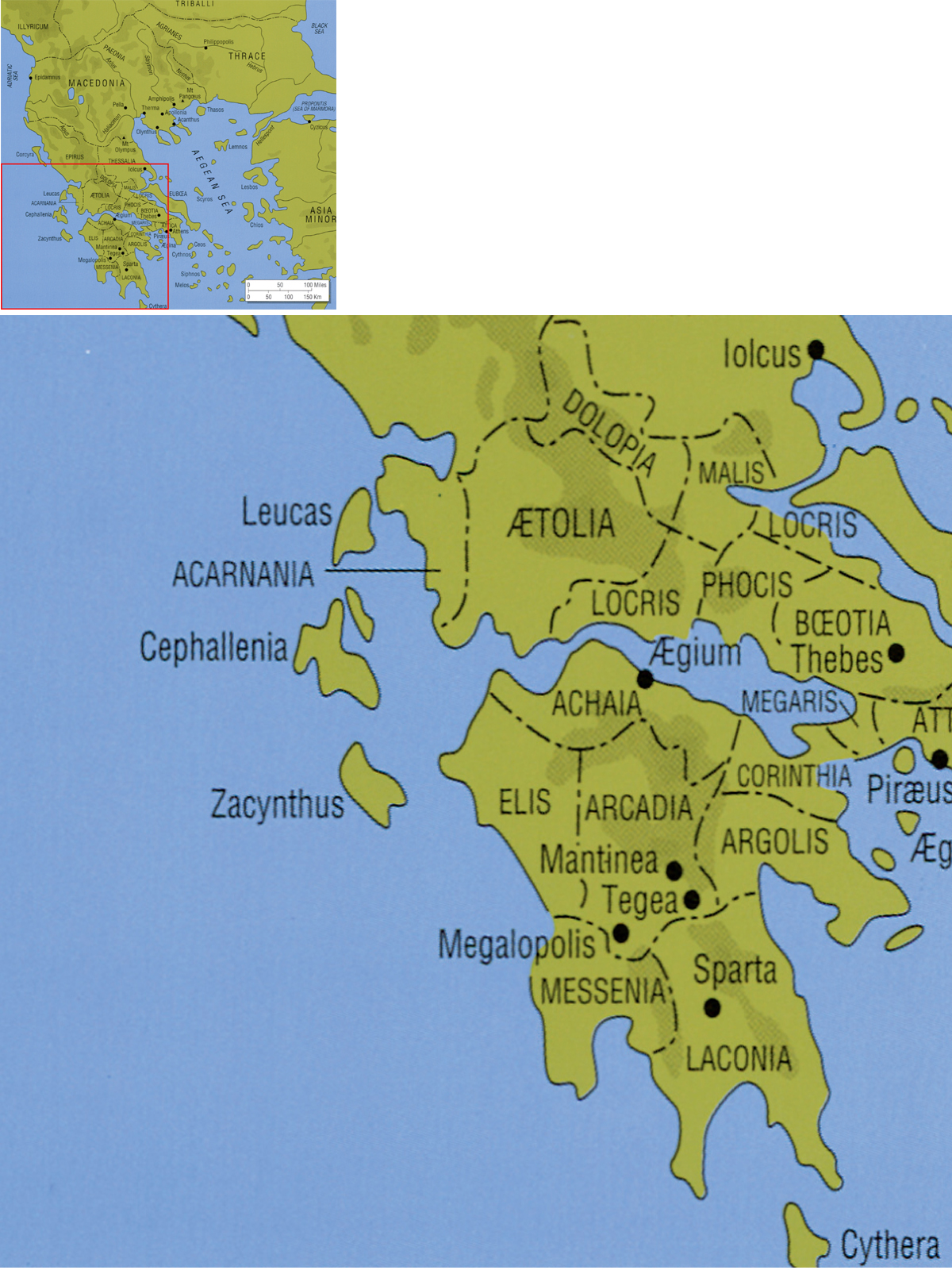

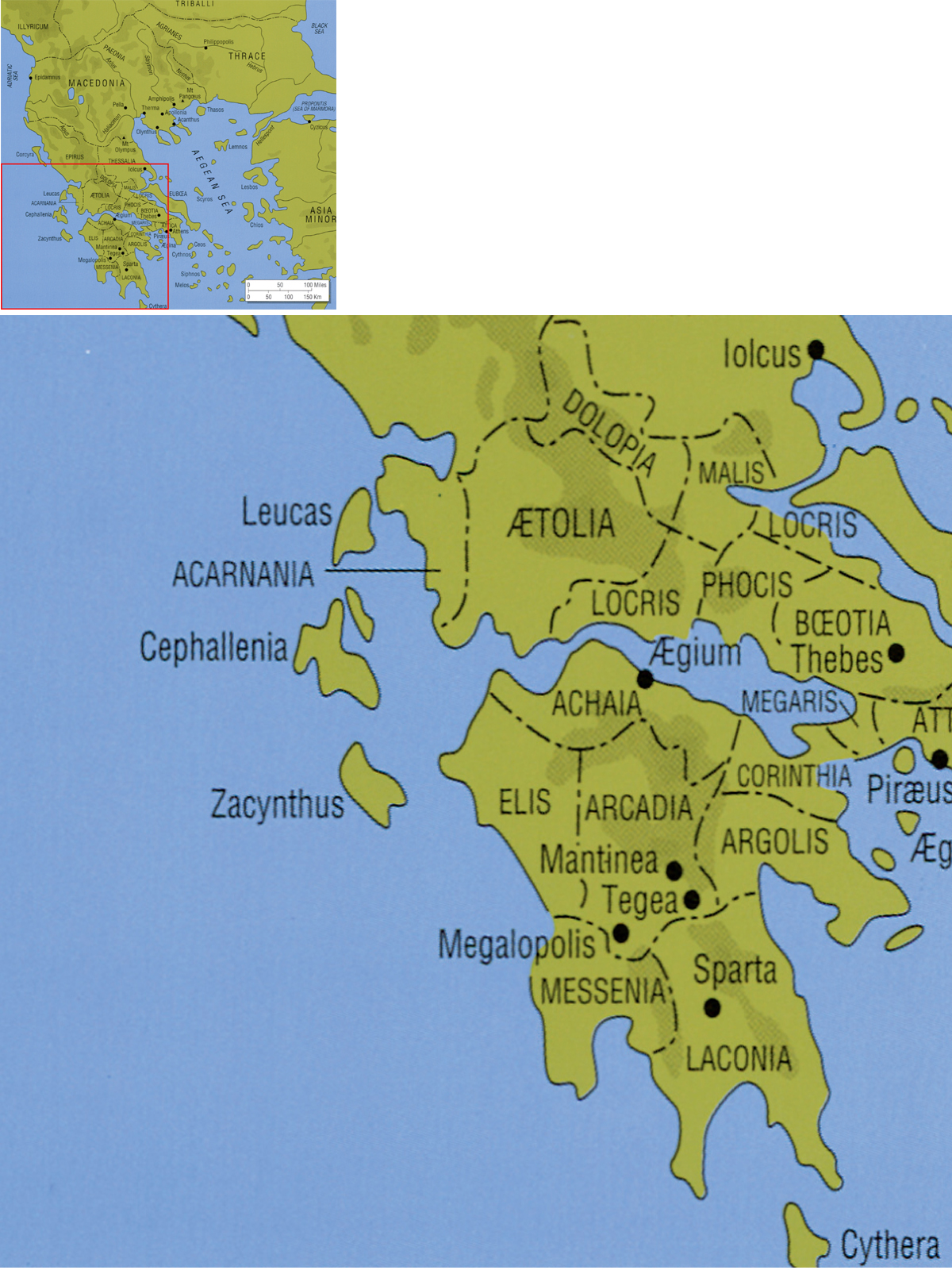

The Persian invasions were repelled and the independence of Greece was secure. But the Greek cities soon relapsed into hostilities among themselves, and the long Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens (431404BC), with its shifting patterns of alliance and confrontation, exhausted Greece. If the Persians were unable to take advantage of Greek weakness, it was because they themselves, following the death of Xerxes in 464BC had entered a period of military weakness. Xerxes immediate successor, Artaxerxes I, showed considerable diplomatic ability, but in 404 Persia lost control of Egypt, and this province was to be recovered for the Persian Empire by Artaxerxes III, with the help of the Greek mercenary leader Mentor, only in 343BC.

In the last years of the Peloponnesian War, the Persian satraps (provincial governors) of Asia Minor, acting sometimes in combination, sometimes independently, alternately lent their support either to Athens or Sparta in a way best calculated to preserve a balance of power and ensure the continuation of the war. The Athenian defeat of 404BC was brought about because Lysander, the Spartan admiral, had been able to rely on Persian money for the equipment and maintenance of a fleet.

But Spartan supremacy soon alarmed the Persians, and an alliance of Persian and Athenian fleets restored the power of Athens by a naval victory at Cnidos in 396BC. Meanwhile, a Greek army of 10,000 men had supported the pretensions of the Persian Prince Cyrus in a war against his brother Artaxerxes II. This army was committed to a march into Mesopotamia and an arduous withdrawal to the Black Sea coast. As a feat of arms the adventure did not escape notice in Greece, and Spartan generals championing the Greek cities of Asia against Persian satraps were encouraged to campaign in the Asian hinterland. But in 386BC, both Sparta and Athens, in return for Persian recognition of their own claims, conceded the right of Persian dominion over the Greek cities of mainland Asia Minor. Even this somewhat cynical peace did not last long, and the pattern of continual warfare in Greece was soon resumed. War was in fact endemic both in Europe and Asia, and the wealth and energies of all states and nations involved was dedicated year after year to acts of violence and destruction, which were not even prompted by any very obvious patriotic motive.

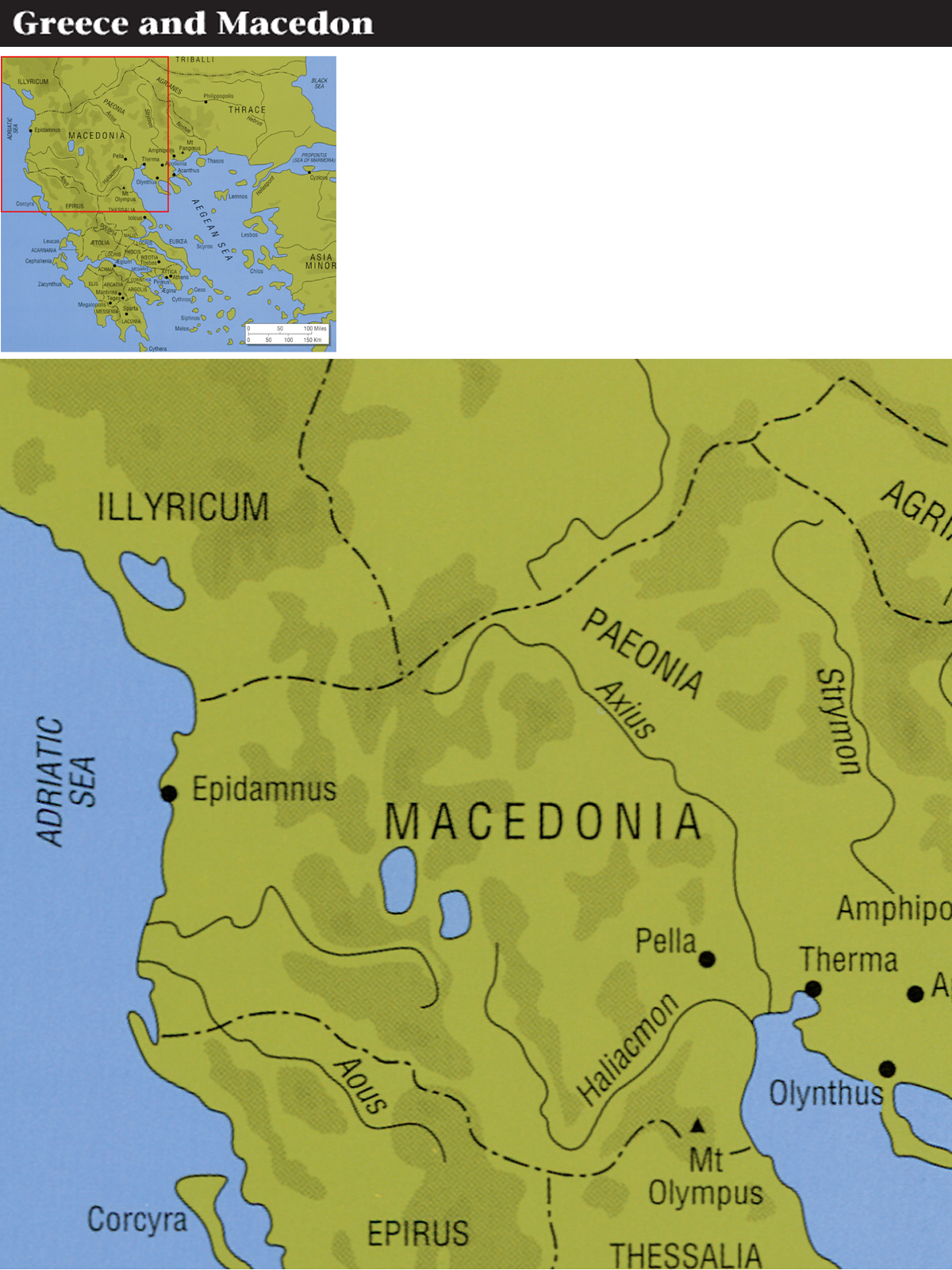

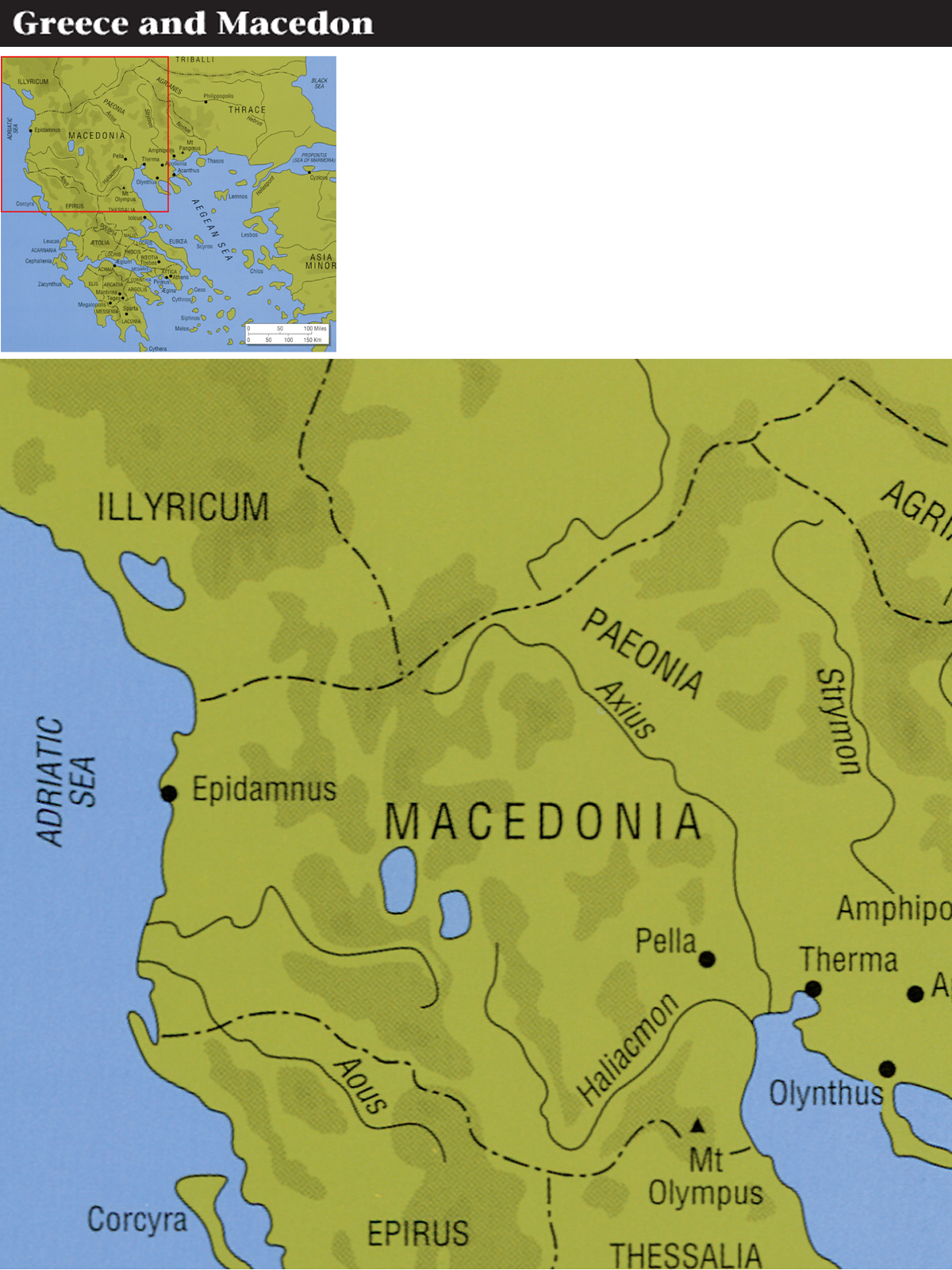

The Rise of Macedon

From this miserable state of affairs, the territory of Macedonia had been largely exempt. Its geographical position and its strategic significance in the first half of the fourth century were of little account in Greco-Persian politics. Notably, it had not been a party to the treaty of 386 which ceded control of the Greek Asian mainland to Persia. That is not to say that the Macedonians were unwarlike. On the contrary, the mixed populations of Macedonia Greek, Thracian and Illyrian jostled each other and resisted encroaching neighbours.

At last in 358BC, the Greek regent of Macedon made himself king. This was Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. With his seat of government at Pella, some twenty miles north of the Thermaic Gulf, Philip asserted his authority over the whole Macedonian territory and extended his frontiers to embrace the Strymon valley in western Thrace with its ready access to silver mines and gold deposits. Within the next twenty years, by use of political opportunism and a highly trained standing army, Philip was able to dominate the whole field of Greek politics. By imposing on the Greeks a peace they were unable to impose upon themselves, he satisfied that personal ambition which is natural to every able statesman and could at the same time justly be regarded as a benefactor of Greek civilization.

Certainly Philip did not impose himself without a diplomatic and military struggle, which was protracted and often deviously conducted, but when Athens and Thebes at last decided to unite their armies against him, he defeated them suddenly and decisively at Chaeronea in Boeotia in 338BC. Sparta remained aloof. But Philip was able to summon a congress of Greek states to a conference at Corinth, from which he emerged as leader of a Greek federation in war against Persia.

The head of Apollo, as was common on coins of Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great, and the inscription on the reverse is that of Philip (Philippou). The name Philip literally means horse-lover, but we should not suspect a deliberate pun: horse types had long been a feature of Macedonian coins and sometimes derive from those of a Thracian mining district occupied by Alexander I of Macedon (498454BC).

War against Persia had gone far to uniting many of the Greek states at the time of Xerxes invasion in 480BC. Leading a similarly combined war effort but this time offensive instead of defensive Philip could hope to assert his authority over Greece both for its own good and for his. He was, however, assassinated in the year 336, as the result of a domestic plot. Alexander, then twenty years old, executed the murderer without asking questions: perhaps he guessed that the crime had been instigated by his mother, Olympias, in his own interest for Philip made no pretence to monogamy. At all events, Alexander now inherited his fathers kingdom and all that went with it.

Alexander in Charge

Although the war against Persia was for Alexander, as for Philip, a prime political and military aim, he was immediately called to wars nearer home. Philips pan-hellenic policies had admittedly found friends as well as enemies in Greece. But Alexanders swift descent with his army through Thessaly and Thermopylae (336) was in itself enough to discourage any independent aspirations among the Greek cities, who quickly recognized him as his fathers successor in all that concerned the war against Persia.

Alexander soon made sure that Greece was controlled by Macedonian garrisons or sympathetic politicians. To these latter the term puppets cannot be quite fairly applied: they included sincere men as well as timeservers. In any case, Greece remained tranquil while in 335 Alexander was called away to secure his garrisons in Thrace against rebellion. The tribes in question were receiving help from Scythian allies across the Danube, but Alexander unexpectedly transported his Army across the Danube in local fishing boats and put an end to hostilities on this front. Having the Persian war in mind, he certainly needed to leave Thrace fully pacified, for it lay on the route to the Hellespont (Dardanelles) and the Persian hinterland.

Next page