Guide To

The Wars of Alexander the Great

336 323 BC

Waldemar Heckel

Contents

Introduction

The conquests of Alexander the Great form a watershed between the world of the Greek city-state (polis) and the so-called Hellenistic world, the eastern kingdoms, where Alexanders successors applied a veneer of Greek culture and administration to a barbarian world. These ancient Near Eastern territories had always been the battleground between eastern and western civilisations, and would continue to be so well beyond the chronological confines of the ancient world.

Western contact with the Near East had begun in the Bronze Age, in Hittite Asia Minor, in the Orontes valley of Syria and in the Nile delta of Egypt. The spectacular frescoes and other artefacts of the prehistoric civilisations of the Aegean depict contact, friendly and hostile, between foreigners and MycenaeanMinoan Greeks. Even after the fall of Troy ended what the historian Herodotus regarded as the first great struggle between east and west, and after the collapse of the Bronze Age civilisations under circumstances that are still not clear new waves of Greek migrants splashed against the shores of Asia Minor. From there, they spread to the Black Sea coast and the Levant, and eventually to the west as well.

By the sixth century BC, however, Greek settlements in Asia Minor became subject to the authority of the Lydians. This kingdom had allied itself with the Medes, who ruled the Persians from Ecbatana (modern Hamadan) until they were overthrown by Cyrus the Great. Croesus, whose name is synonymous with fabulous wealth, was the last of the Lydian rulers and, in 548/7, he raised an army against the Persian upstart, misled by Greek oracles into thinking that he would acquire a greater empire. After an indecisive battle near the Halys, the Lydian troops disbanded, as was their practice for it was not customary to wage war over the winter months but Cyrus brought his Persians up to the walls of Sardis, seized its citadel and put Croesus to death. (Greek tradition was embarrassed by the oracles deception and maintained that Apollo intervened at the last minute, saving Croesus from the flames and transporting him to an idyllic world.)

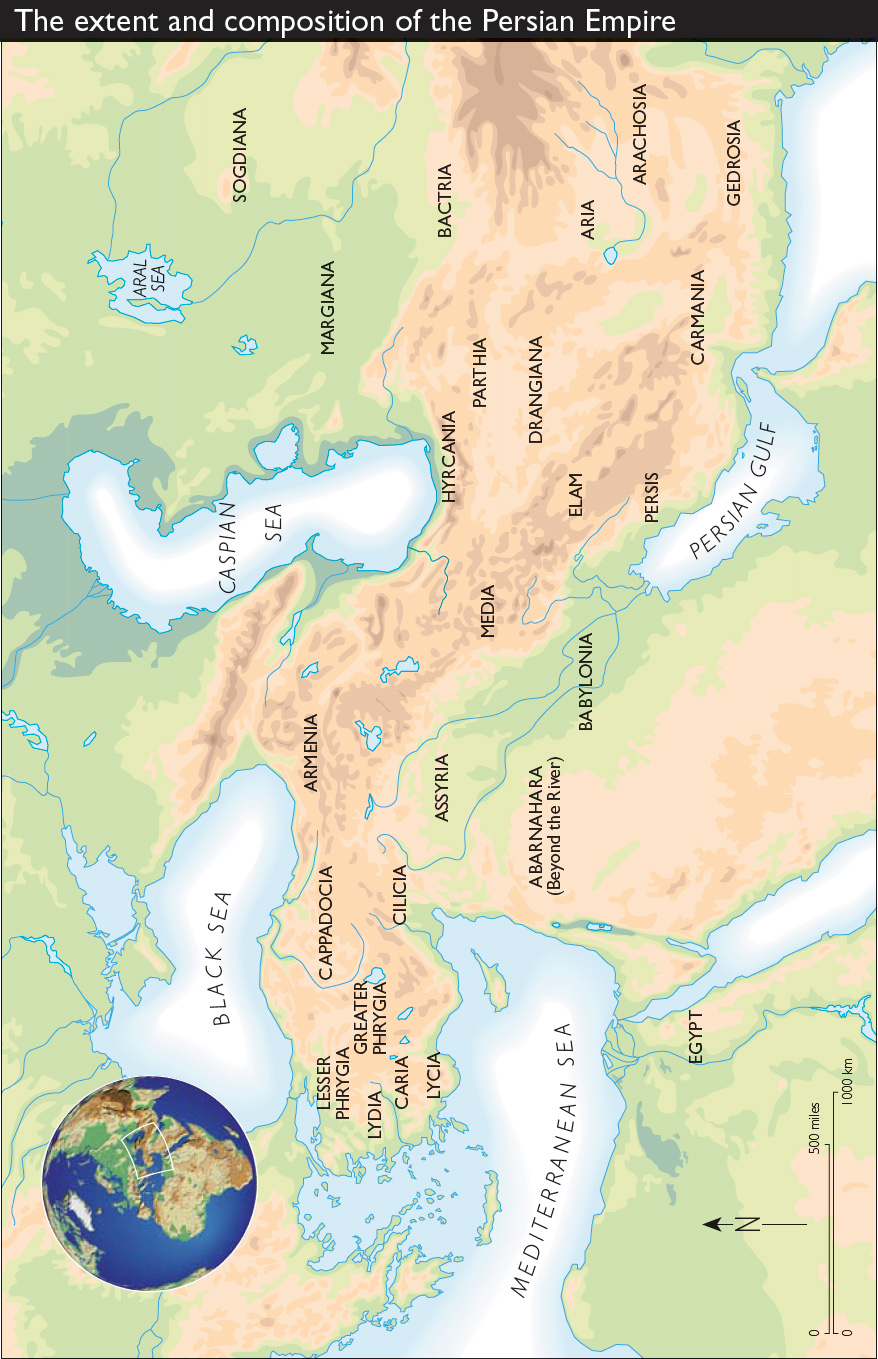

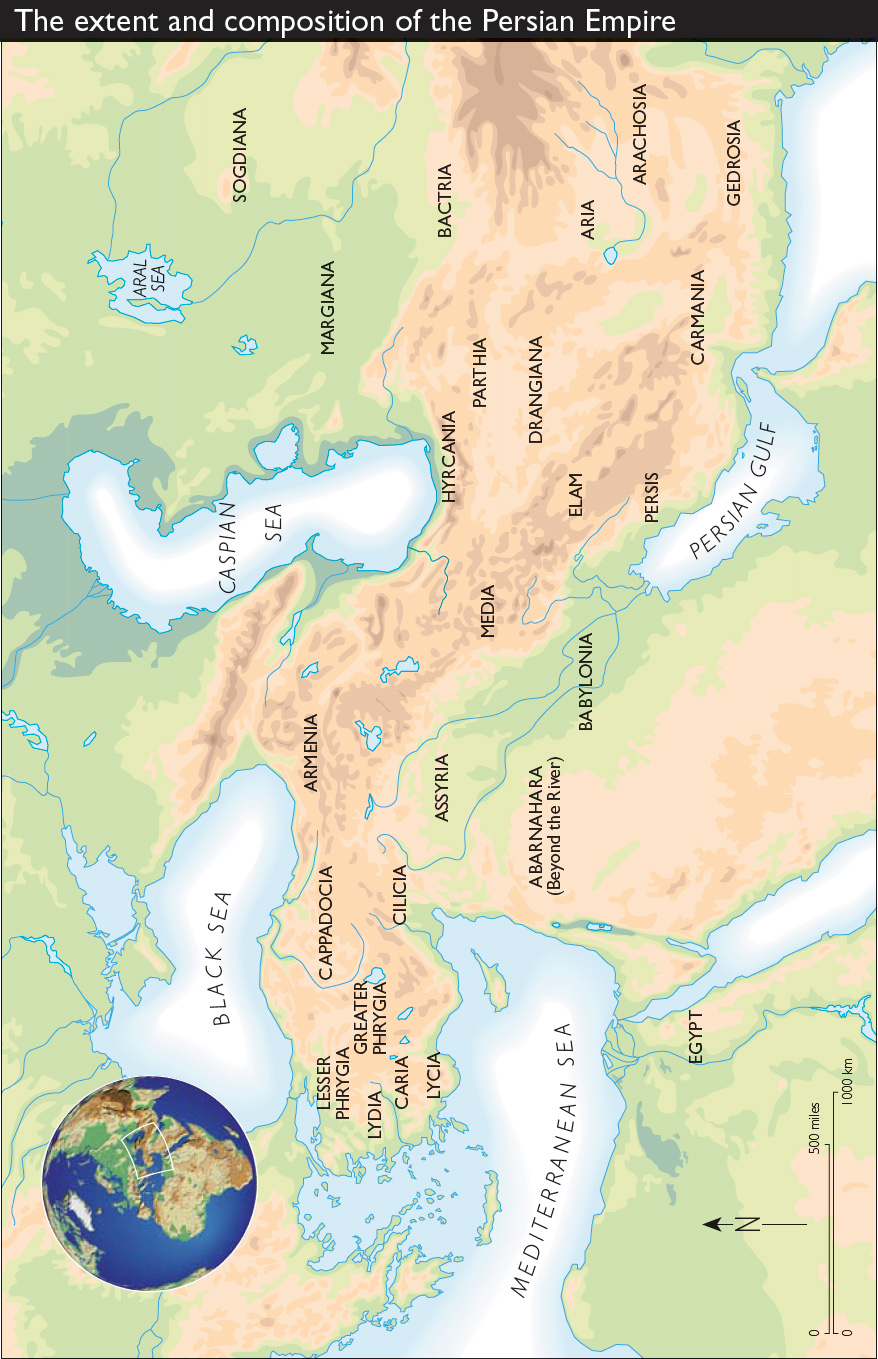

Between 547 and 540 Cyruss generals subdued coastal Asia Minor, while he turned his attention to the Elamites and Babylonians. By the end of the century, the Achaemenids ruled an empire that extended from the Indus to the Aegean and from Samarkand to the first cataracts of the Nile. The title King of Kings was thus no empty boast.

Persian domination of Greek Asia Minor threatened the city-states of the peninsula to the west, as well as the islands that lay in between. In 513 Darius I crossed the Hellespont (Dardanelles), the narrow strait that separates the Gallipoli peninsula of Europe from what is today Asiatic Turkey. Portions of Thrace were annexed and administered as the Persian satrapy of Skudra, and at some point thereafter the Persians received the submission of Macedon. Even the isolationist states to the south, in particular Sparta, were forced to take notice.

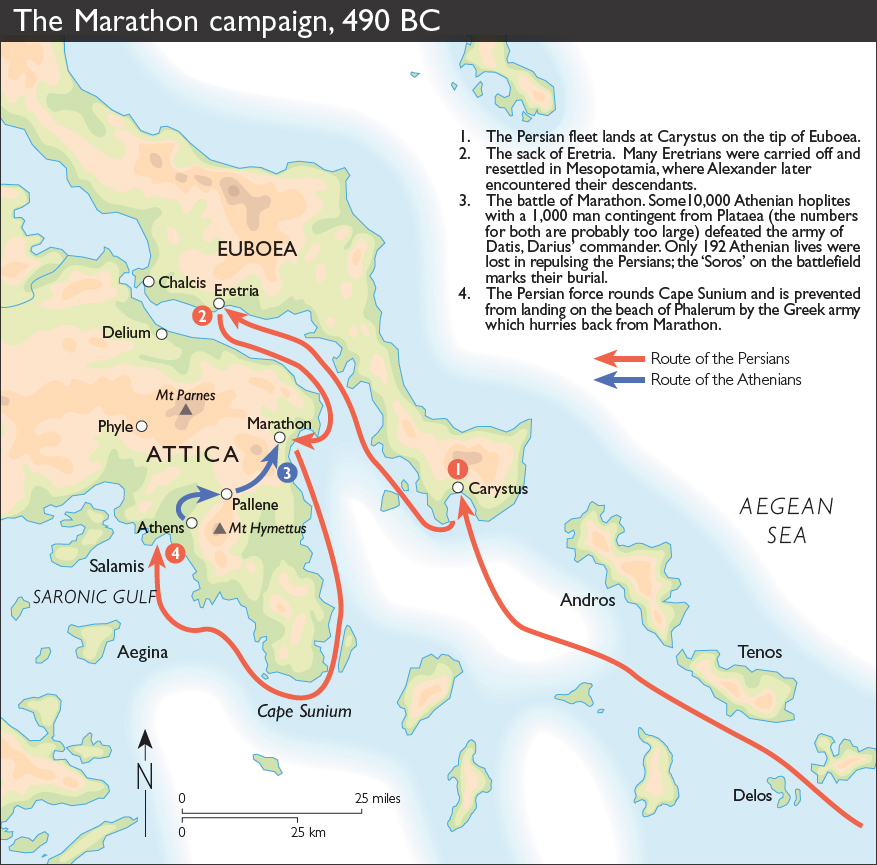

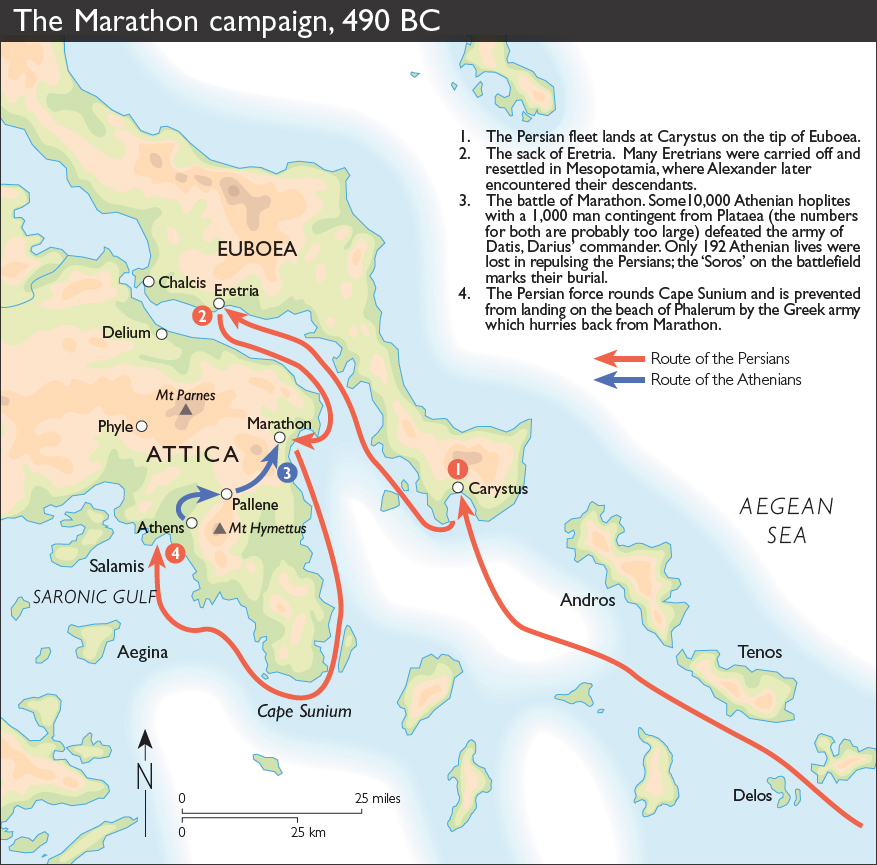

The Athenians and the Eretrians of Euboea had aided a rebellion by the Ionians, futile (as it turned out) attempt to throw off the Persian yoke (499/498494/493). Victorious over the rebels, Darius launched a punitive campaign against their supporters: in 490 his general, Datis, crossed the Aegean and destroyed the city of the Eretrians, many of whom were subsequently enslaved in the heart of the Persian Empire their descendants, the Gortyae, fought Alexander at Gaugamela. Then Datis landed on Athenian soil at Marathon; however, contrary to expectation, a predominantly Athenian force defeated the Persian army.

The Athenian victory provided an immense boost to Greek confidence, which would be put to the test ten years later, when Darius son and successor, Xerxes, came dangerously close to defeating a coalition of Greeks and adding the lower Balkans to the Persian Empire. Only the great naval victory at Salamis (summer 480) prevented the Persian juggernaut from crushing all resistance in Greece. That victory hastened the retreat of Xerxes with the bulk of his army; those who remained under Mardonius were dealt the decisive blow on the battlefield of Plataea in 479.

The ill-fated expedition of Xerxes resulted in strained but stable relations between Greece and Persia, a balance of power that in some respects resembled the Cold War of the twentieth century. The Greek world, however, was itself divided and polarised, with the Spartans exercising hegemony over the Peloponnesian League as a counterweight to Athens, which, under the guise of liberating the Hellenes from Persia, had converted the Delian League originally, a confederacy of autonomous allies into an empire. By the middle of the fifth century, Athens was reaping the financial benefits of the incoming tribute and unashamedly extolling the virtues of power politics. The inevitable clash of Greek powers took place between 431 and 404 and was known as the Peloponnesian War (see The Peloponnesian War in this series). When it was over, the Athenian Empire existed no more and the gradual decline of the Greek city-states through internecine warfare set the stage for the emergence of a great power in the north: the kingdom of Macedon.

Demosthenes on Persia

I consider the Great King to be the common enemy of all the Greeks Nor do I see the Greeks having a common friendship with one another, but some trust the King more than they do some of their own [race].

Demosthenes 14.3

The struggle for hegemony amongst the city-states of Sparta, Thebes and Athens made it clear that Greek unity the elusive concept of Panhellenism was something that could not be achieved peacefully, through negotiation or commitment to a greater purpose; rather it was something to be imposed from outside. Earlier the Greeks had closed ranks in order to resist the common enemy, Persia. But when the threat receded, the Hellenic League dissolved and the political horizons of the Greeks narrowed. Certain intellectuals nevertheless promoted the concept of Panhellenism, even if it meant the forcible unification of the city-states. When Philip achieved this, by means of his victory at Chaeronea and the creation of the League of Corinth, he attempted to renew Panhellenic vigour by reminding the Greeks of the common enemy, the Persians.

The concept of a war of vengeance was, however, a hard sell. Although some appealed directly to Philip to bring about the unification of Greece and lead it against Persia, others, like Demosthenes, who criticised the interference of the Persian King in Greek affairs, espoused Panhellenism only if it could be accomplished under Athenian leadership or for Athenian benefit. And there were like-minded politicians in the other poleis who favoured unity under the hegemony of their own states. In the face of Macedonian imperialism, Demosthenes was content at least, according to his accusers to accept Persian money to resist Philip and Alexander.

Chronology

| 560550 | The rise of Cyrus the Great |

| 547 | Cyrus defeats Croesus of Lydia |

| 513 | Darius Is invasion of Europe results in near disaster north of the Danube |

| 499493 | The Ionian Revolt |