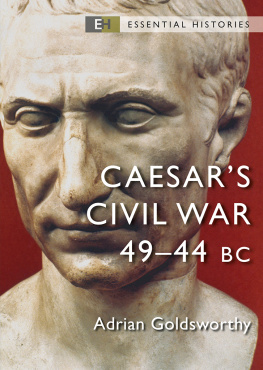

Guide To

Caesars Civil War

4944 BC

Adrian Goldsworthy

Contents

Introduction

The Roman Republic and its growing problems

Although originally a monarchy, Rome had become a Republic near the end of the sixth century BC. Such political revolutions were commonplace in the city-states of the ancient world, but after this Rome proved remarkably stable, free from the often violent internal disputes that constantly beset other communities. Gradually at first, the Romans expanded their territory, and by the beginning of the third century BC they controlled virtually all of the Italian peninsula. Conflict with Carthage, which began in 265 (all dates are BC unless stated otherwise) and continued sporadically until that city was utterly destroyed in 146, resulted in the acquisition of overseas provinces. By this time Rome dominated the entire Mediterranean world, having defeated with ease the successor kingdoms which had emerged from the break-up of Alexander the Greats empire.

Roman expansion continued, and time and time again her legions were successful in foreign wars, never losing a conflict even if they sometimes suffered defeat in individual battles. Yet, the stability and unity of purpose which had so characterised Roman political life for centuries began to break down. Politicians started to employ violent means to achieve their ends, the disputes escalating until they became civil wars fought on a massive scale. A succession of charismatic military leaders emerged, men able to persuade their soldiers to fight other Romans. In 49 Julius Caesar, faced with the choice between being forced out of politics altogether or starting a civil war, invaded Italy. His success effectively tolled the death knell of the Republican political system, for after his victory he established himself as sole ruler of the Roman world. Caesar was murdered because his power was too blatant, and the assassination returned Rome to another period of civil war, which ended only when Caesars nephew and adopted son Octavian defeated his last rival in 31. It was left to Octavian, later given the name Augustus, to create the regime known as the Principate, a monarchy in all but name, returning stability to Rome and its empire at the cost of a loss of political freedom.

The Roman republican system was intended to prevent any individual or group within the state from gaining overwhelming and permanent power. The Republics senior executive officers or magistrates, the most senior of whom were the two consuls, held power (imperium) for a single year, after which they returned to civilian life. A mixture of custom and law prevented any individual being elected to the same office in successive years, or at a young age, and in fact it was rare for the consulship to be held more than twice by any man. Former magistrates, and the pick of the wealthiest citizens in the state formed the Senate, a permanent council which advised the magistrates and also supervised much of the business of government, for instance, despatching and receiving embassies. The Senate also chose the province (which at this period still meant sphere of responsibility and only gradually was acquiring fixed geographical associations) to be allocated to each magistrate, and could extend the imperium of a man within the same province for several years.

Roman politics was fiercely competitive, as senators pursued a career that brought them both civil and military responsibilities, sometimes simultaneously. It was very rare for men standing for election to advocate any specific policies, and there was nothing in any way equivalent to modern political parties within the Senate. Each aristocrat instead tried to represent himself as a capable man, ready to cope with whatever task the Republic required of him, be it leading an army or building an aqueduct. Men paraded their past achievements and since often before election they personally had done little the achievements of past generations of their family. Vast sums of money were lavished on the electorate, especially in the form of games, gladiator shows, feasts and the building of great monuments. This gave great advantages to a small core of established and exceptionally wealthy families who as a result tended to dominate the senior magistracies. In the first century there were eight praetorships (senior magistracies of lower ranking than consulships), and even more of the less senior posts, but still only ever two consulships. This meant that the majority of the 600 senators would never achieve this office. The higher magistracies and most of all the consulship offered the opportunity for the greatest responsibilities and therefore allowed men to achieve the greatest glory, which enhanced their family name for the future. The consuls commanded in the most important wars, and in Rome military glory always counted for more than any other achievement. The victor in a great war was also likely to profit from it financially, taking a large share of the booty and the profits from the mass enslavement of captured enemies. Each senator strove to serve the Republic in a greater capacity than all his contemporaries. The propaganda of the Roman lite is filled with superlatives, each man striving to achieve bigger and better deeds than anyone else, and special credit was attached to being the first person to perform an act or defeat a new enemy. Aristocratic competition worked to the Republics advantage for many generations, for it provided a constant supply of magistrates eager to win glory on the states behalf.

However, in the late second century BC the system began to break down. Rome had expanded rapidly, but the huge profits of conquest had not been distributed evenly, so a few families benefited enormously. The gap between the richest and poorest in the Senate widened, and the most wealthy were able to spend lavishly to promote their own and their familys electoral success. It became increasingly expensive to pursue a political career, a burden felt as much by members of very old but now modestly wealthy families as by those outside the political lite. Such men could only succeed by borrowing vast sums of money, hoping to repay these debts once they achieved the highest offices. The risk of failure, which would thus bring financial as well as political ruin, could make such men desperate. At the same time men from the richest and most prestigious families saw opportunities to have even more distinguished careers than their ancestors by flouting convention and trying to build up massive blocks of supporters. Both types were inclined to act as populares, an abusive term employed by critics to signify men who appealed to the poorer citizens for support by promising them entertainment, subsidised or free food, or grants of land. The popularis was an outsider, operating beyond the bounds of and with methods unattractive to the well-established senators. It was a very risky style of politics, but one which potentially offered great opportunities. In 133 a radical tribune the ten tribunes of the plebs were magistrates without military responsibilities who were supposed to protect the interests of the people from one of the most prestigious families, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, was lynched by a mob of senators when he tried to gain re-election to a second year of office. In 121, his brother Caius, who pursued an even more radical agenda, was killed by his opponents in something that came close to open fighting in the very centre of Rome. Yet a small number of men began to have previously unimaginable electoral success, as many of the old precedents restricting careers were broken. From 104 to 100, a successful general named Caius Marius was elected to five successive consulships.