CROSSING THE RUBICON

Originally published in Italian as Il dado tratto. Cesare e la resa di Roma

2017 Gius. Laterza & Figli. All rights reserved.

First published in English by Yale University Press in 2019.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947812

ISBN 978-0-300-24145-7

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

MAPS

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

The chronological references relating to the events and to the early sources are all to be understood as BC , unless otherwise indicated. The dates are those of the republican calendar prior to Caesars reform in 46 BC (and which made it necessary, among other things, to recover more than two months in order to bring the official year in line with the astronomical year).

TRANSLATORS NOTE

The translations of all quotations throughout this book are my own. Where possible, I have consulted the translations referred to in the Bibliography and Further Notes below, in particular the translations of Ciceros letters published by Cambridge University Press, but have also used the invaluable Perseus Digital Library and other online resources. My special thanks to Giuliana Paganucci for her advice on the interpretation of particular words and phrases, and to Peter Greene for his comments and suggestions for improvements to the translation.

A NOTE ON SOURCES

In retelling the events of 49 BC , I draw extensively on Ciceros letters. Marcus Tullius Cicero (10643) was an orator, politician and tireless letter-writer and an important contemporary voice. His letters, much more authentic inasmuch as they were not meant for publication, reveal their author to be the personality of the ancient world whom we know best in the hidden corners of his mind. The letters also offer a lively glimpse of Romes short century, or its age of revolution, populated by the restless and extraordinary last generation of the res publica. Among his correspondents were Caesar and Pompey.

The material is vast and hitherto undervalued. The letters, often referred to as hysterical, have only fuelled depictions of Cicero as incapable of political judgement and struck by chronic blindness.

As historians, we are fortunate to possess such a rich testimony for this crucial period rich, although unreliable in its objectivity since Cicero vacillated in his views as a result of partial or false news that he received about the war. Nonetheless, not all of Caesars adversaries could boast equal lucidity, coherence, nor indeed heroism. The correspondence is therefore valuable, particularly those letters addressed in the early months of 49 to Titus Pomponius Atticus (11032) who was not only a friend but also his brother-in-law (Tituss sister Pomponia had married Ciceros brother Quintus). It is also valuable as long as we keep in mind that it is the product of a man from the ruling class a class which had in Pompey an uncertain leader and strategist. The correspondence therefore reflects the elites anxieties at that time.

Atticus himself, a cultured intellectual and very well-informed businessman, was a point of reference for many people during those days of turmoil. To friends leaving to join Pompey he gave what was necessary from his own pocket and in this way did not offend the feelings of Pompey (whose wife Cornelia was related to Atticus maternal uncle); Caesar appreciated his neutrality, so much as to prize him. He would have preferred to follow the chariot of triumphant Caesar so long as the two contenders came to an agreement; he gave advice to the former, pleading several times with the latter, trying to mollify and pacify both of them. When the situation deteriorated and Pompey left Rome, Cicero did not flee but seemed to be trying to attach himself to Caesar. Tormented by doubts, he did not know which side to take. The jurist Gaius Trebatius Testa wrote to him that, in Caesars view, he ought to have joined his side; but if he felt unable by reason of advanced age, he would be better off going to Greece and living there in peace, far away from both. Cicero, amazed that Caesar hadnt written to him personally, replied angrily that he would do nothing that was unworthy of his past political record. The episode in question can be read in his letters.

In the chaotic tragedy of the res publica, Ciceros correspondence seems in our view, as it did to Plutarch, to be a mine of information: on the lack of preparation in Pompeys camp, on the difficulties in communication, on the opportunistic behaviour of the ruling class, on the fate of the ancient city-state which had now become a megalopolis and which Cicero feared could be prey to anarchy and starvation. Neither of

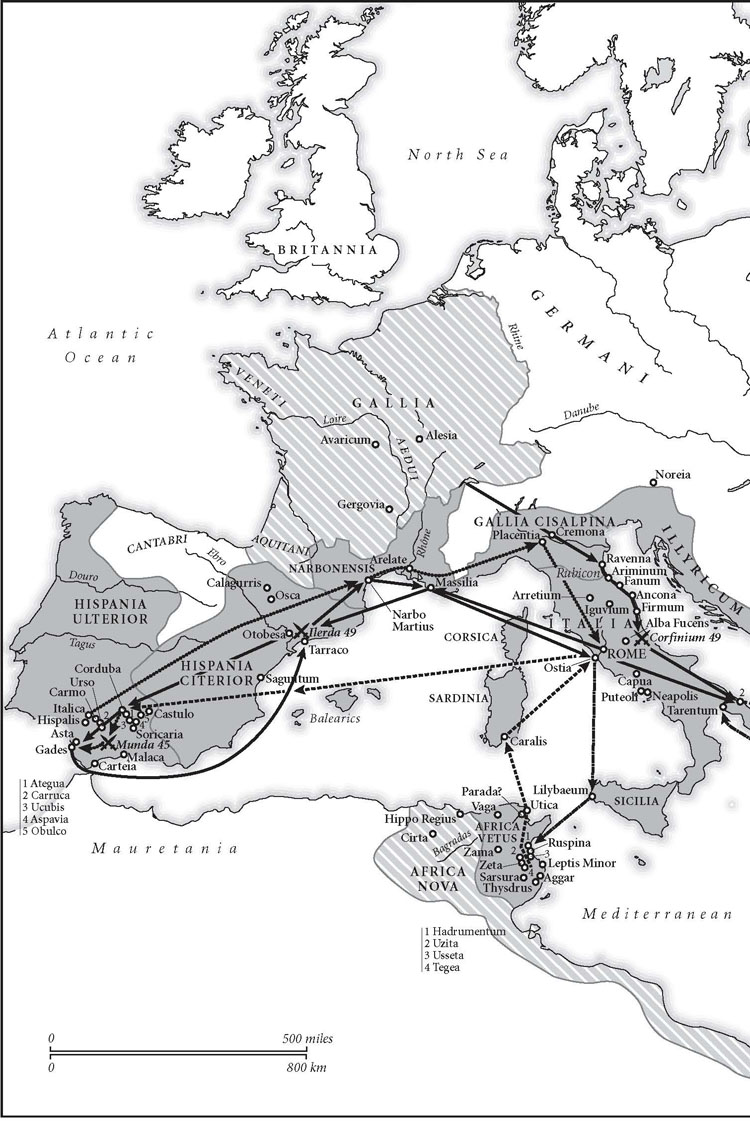

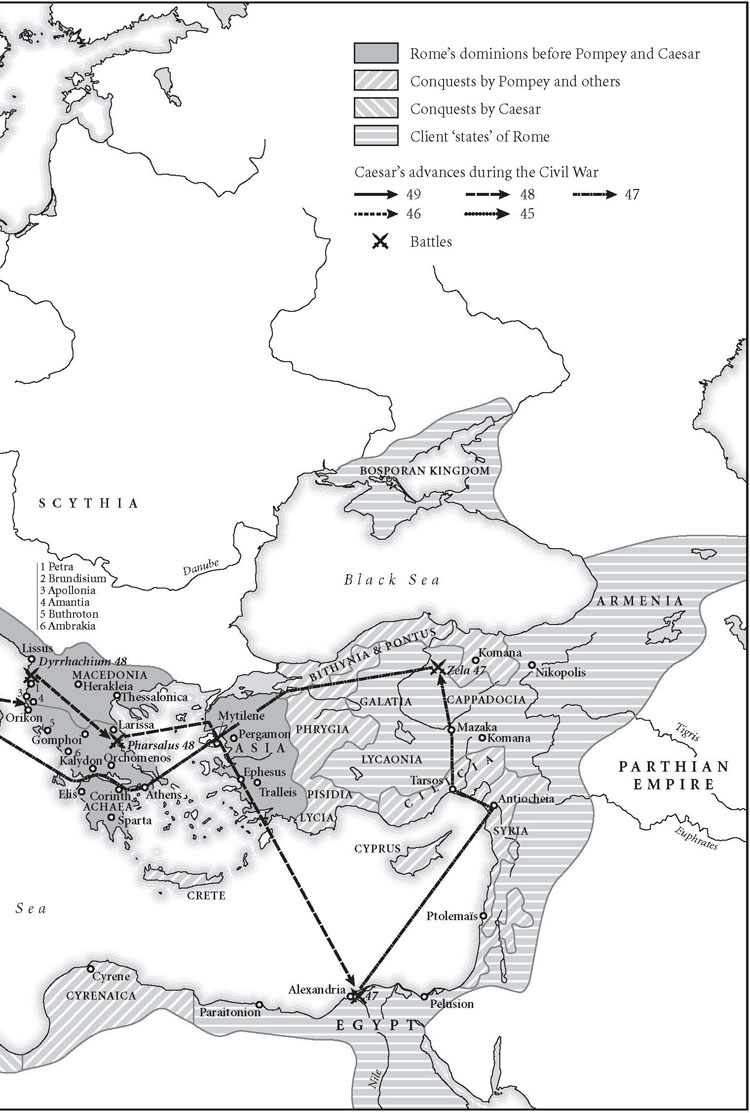

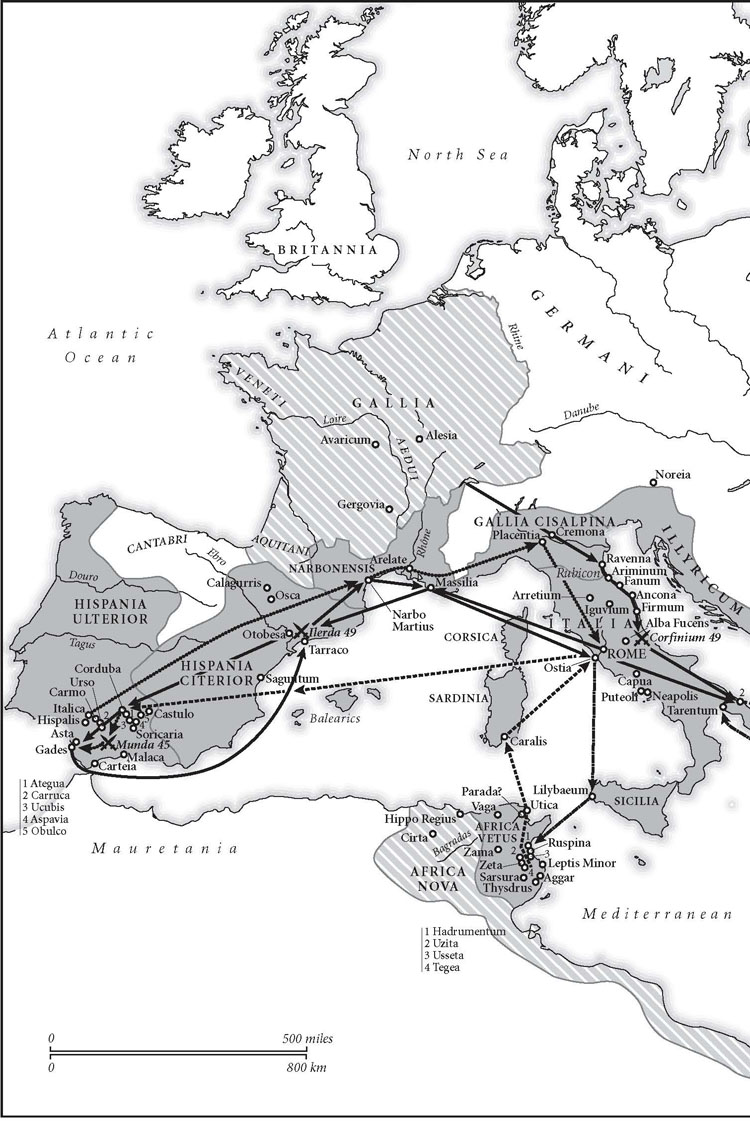

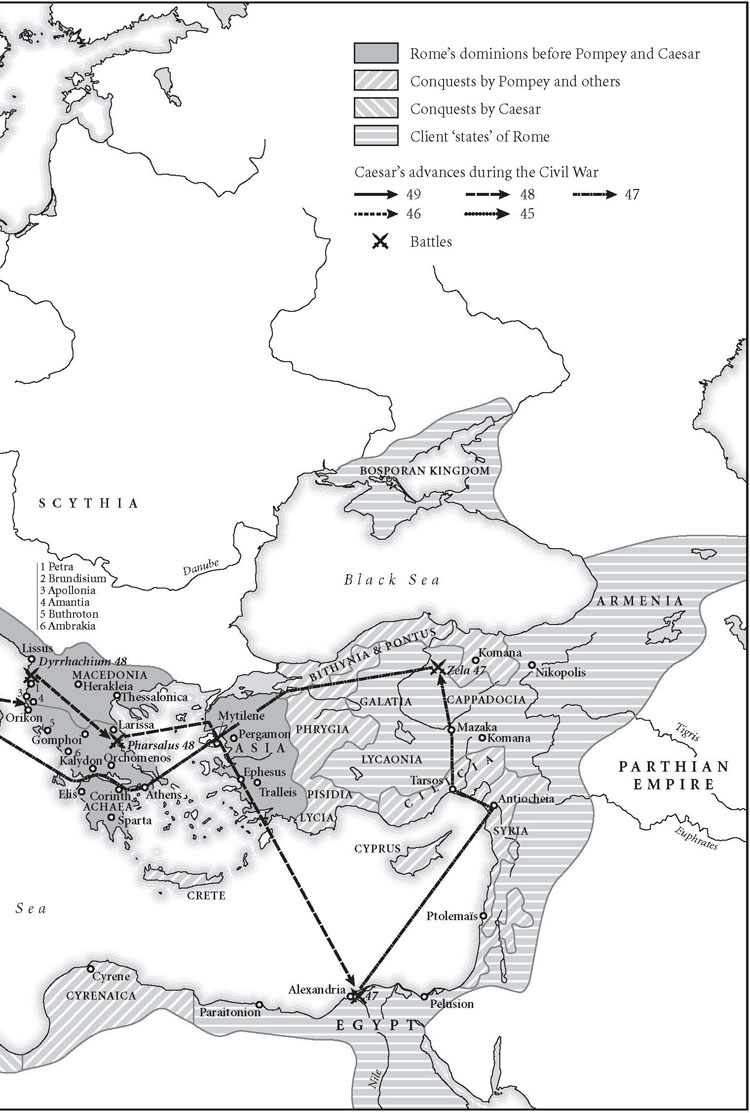

Map 1 The Roman world and the Civil War of 4945

PROLOGUE

What he did after he left Ravenna

and leapt the Rubicon, was such a flight,

as neither tongue nor pen could follow.

Dante, Paradise, 6,613

In 49 BC , a crowd of soldiers was waiting for its commander to arrive. For some time, the soldiers had been gathered along the northern bank of one of the streams that crossed their route towards nearby Rimini. The commander was making his way to them under the cover of night, but had got lost several times. Forced to abandon his mules and wagon, he sought the help of a local guide who led him on foot along narrow paths. Finally, he arrived in the early morning of 11 or 12 January and stood before his troops. He hesitated.

Gaius Julius Caesar, patrician, pontifex maximus and proconsul, knew that when he led his men across the small stream ahead the Rubicon he would trigger a war he could not be sure of winning. The Rubicon was the border between the south-eastern corner of Cisalpine Gaul and terra Italia. Cisalpine Gaul was a province, a territory subject to Rome and governed at that time by Caesar; terra Italia was the peninsular area of Italy, whose inhabitants some forty years before had received Roman citizenship. By crossing the Rubicon, Caesars men would be defying a twofold prohibition and an ultimatum recently issued by Rome. The twofold prohibition forbade the leading of armies outside a commanders own province particularly in terra Italia without the authorization of the Senate (the assembly of ex-magistrates that regulated Roman foreign policy). The ultimatum, which was issued soon after the declaration of a state of emergency, instructed Caesar to disband his troops.

Caesar knew that crossing the Rubicon was the point of no return. But he had a strategic objective to achieve. His aim was to occupy Ariminum (present-day Rimini), an ancient colonia built as a garrison against Gallic invaders and the first municipium urban centre of Roman citizens to be reached on entering terra Italia

Next page