OSPREY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Kemp House, Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford OX2 9PH, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

E-mail:

www.ospreypublishing.com

OSPREY is a trademark of Osprey Publishing Ltd

First published in Great Britain in 2023

This electronic edition published in 2023 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2023

The text in this edition is revised and updated from: ESS 42: Caesars Civil War: 4944 BC (Osprey Publishing, 2002).

Essential Histories Series Editor: Professor Robert ONeill

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4728-5507-7 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-5506-0 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-5505-3 (ePDF)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-5508-4 (XML)

Cover design by Stewart Larking

In reference to the image : Isteni, Janka,

ROMAN MILITARY EQUIPMENT FROM THE RIVER

LJUBLJANICA. Typology, Chronology and Technology.

Catalogi et monographiae 43, Ljubljana 2019, p. 261, fig. A1.1a.

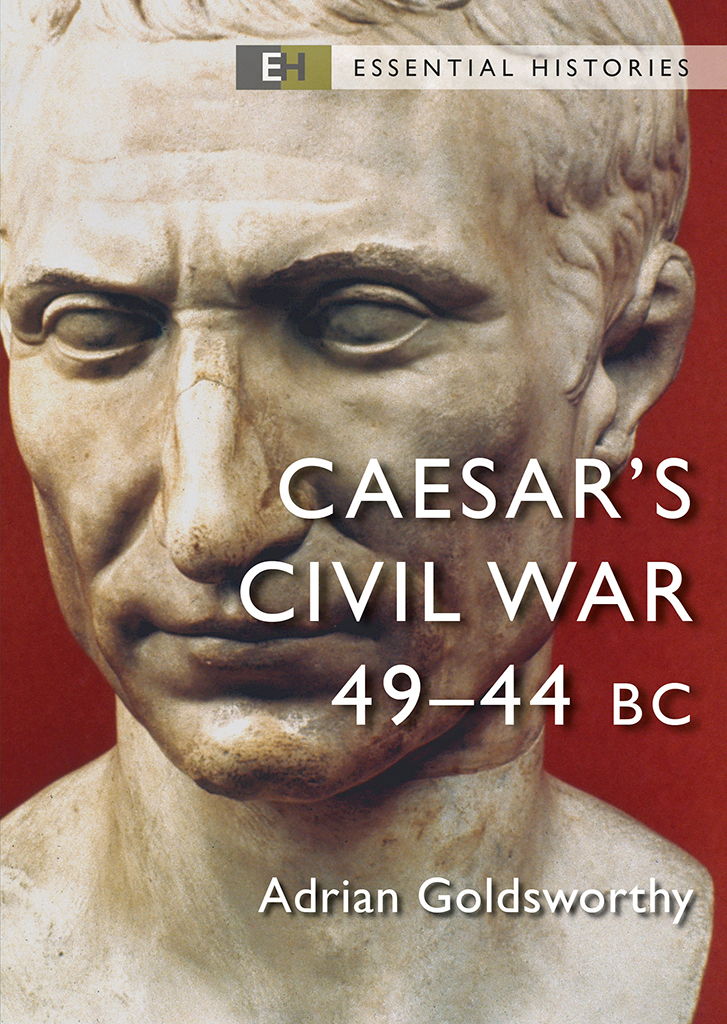

Front cover image: Roman bust of JuliusCaesar. (GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo)

Maps by The Map Studio, revised by J B Illustrations

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find our full range of publications, as well as exclusive online content, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters. You can also sign up for Osprey membership, which entitles you to a discount on purchases made through the Osprey site and access to our extensive online image archive.

CONTENTS

The First Triumvirate

Legion against legion

Crossing the Rubicon

Civil War

A Mediterranean war

The Ides of March

Civil wars and the end of the Republic

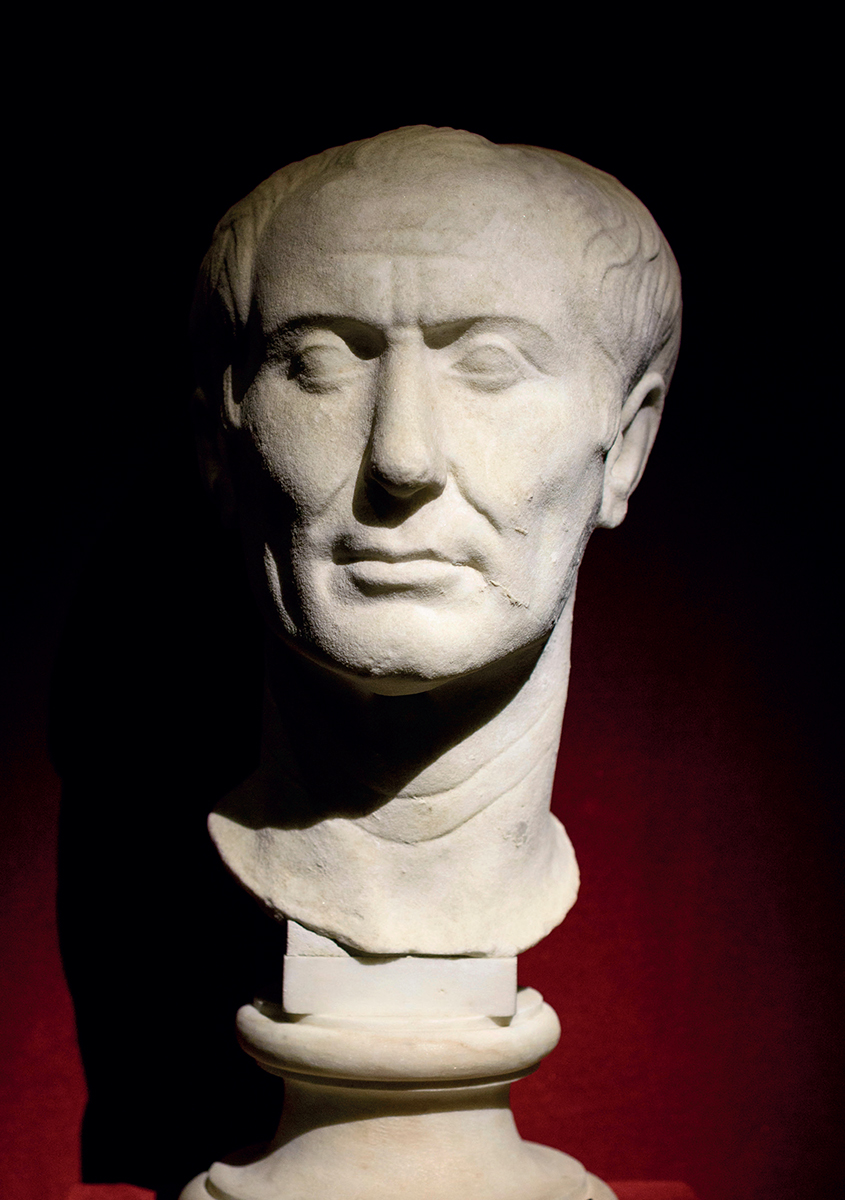

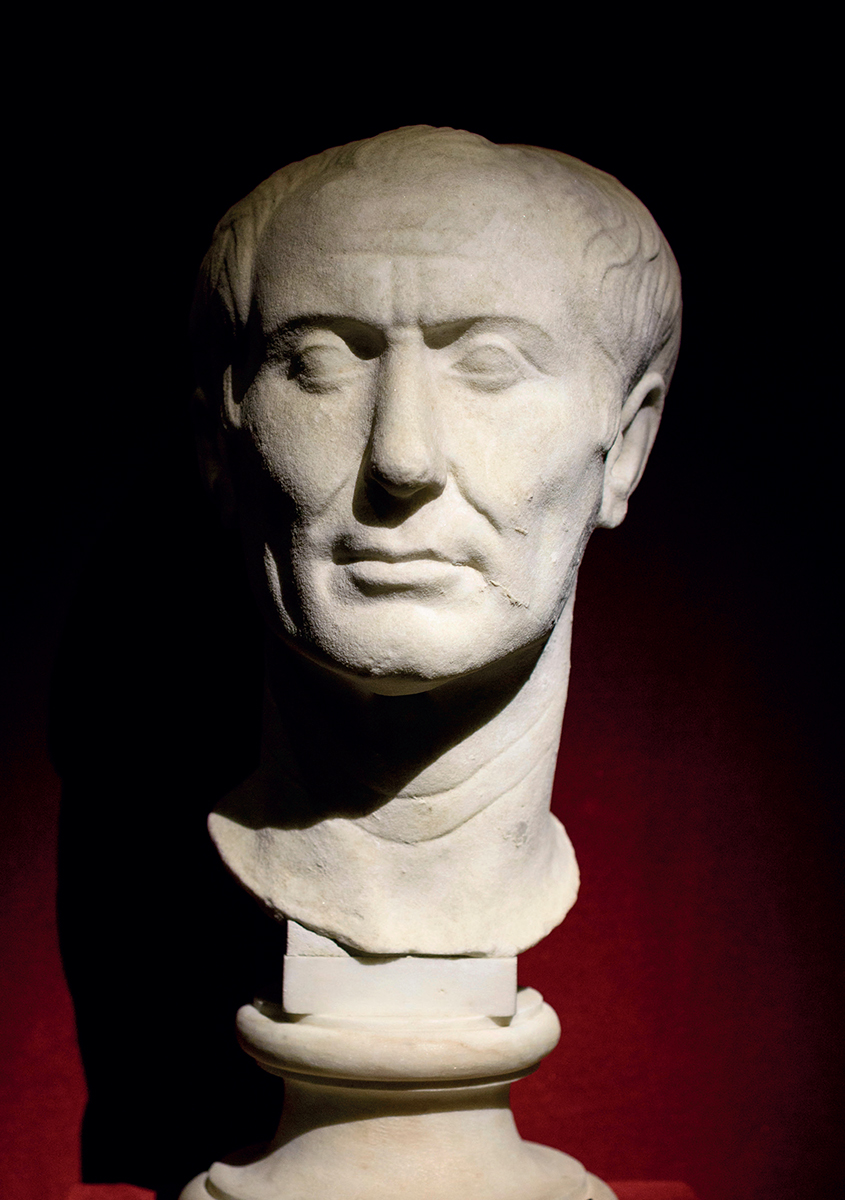

This bust from Tusculum is probably the most accurate depiction of Caesar in later life. Many of the later images of Caesar tended to idealise his features. (Adam Eastland Art + Architecture / Alamy Stock Photo)

Julius Caesar remains famous to this day, even though the Classics no longer play much role in education. He is remembered as a statesman, as a great soldier, as the lover of Cleopatra, and because of Shakespeares play (even though he is murdered early in Act 3 and the real tragic hero of the play is Brutus). Journalists use expressions like Crossing the Rubicon, The die is cast, or The Ides of March, confident that the references will be sufficiently understood to make their point. All three refer to moments covered in this book.

Caesar was widely considered the most successful commander in Romes history, with Pliny the Elder noting that he fought and won more battles than anyone else, although also lamenting the heavy death toll resulting from his campaigns. Yet like all Roman commanders until Late Antiquity, Caesar was not a full-time soldier, but a politician following a career in public life that brought him civil as well as military posts. In his youth he spent little time with the army, although he managed to win an award for bravery, the corona civica, in his late teens and gave hints of immense self-confidence. At the age of 39 he was appointed to govern one of Romes Spanish provinces and from then on until his death in his 56th year, his life was dominated by warfare in way that had never been true before. Thus, the battles Pliny mentions were all fought in this last period of his life and it was then that he forged his reputation as a military genius. Hindsight means that we do not find any of this surprising, but like Alexander or Napoleon or Lee we come to his campaigns expecting to see signs of immense talent and knowing that as military leaders these men were special. At the time, Romans, and especially other senators, had no reason to expect that Caesar would overrun Gaul so rapidly. Even after this, they may have wondered whether Caesar and his army would match up so well against disciplined opponents, let alone against the proven talent of Pompey. Whatever their feelings about Caesar and his cause, relatively few senators shared Caelius Rufus opinion that he had the better army and was much more likely to win. Far more of them placed their trust in Pompeys record, and, after his death, in the prestige of the remaining commanders, or preferred to remain neutral.

Caesar was not simply a great general, but a remarkably fluent writer and it is well known that the bulk of our evidence for his campaigns comes from his own Commentaries. (In the case of the Civil Wars, we are a little better off as from the end of 48 BC the accounts of the remainder of the conflict were written by others after Caesars death, albeit by men who had served under him and were admirers). Many generals would surely envy this, although few men of action have matched Caesars skill with words Churchill is an obvious exception, but there are not many others. Overtly dispassionate, referring to himself in the third person, and often vague about his own activities, allowing readers or at the time often listeners, since books were expensive and public readings common to imagine for themselves appropriately heroic actions, the Commentaries combine pacy storytelling with self-serving propaganda. Whatever the details, the overwhelming impression is that when Caesar was present or his influence most obviously felt the right decisions were made and his men fought with an unsurpassed skill and heroism as true Romans. That critics of individual decisions or of Caesars generalship more widely have found plenty of ammunition in his own narrative, let alone reading between the lines of his account, highlights its essential honesty, but also its subtlety. Allowing the reader to see apparent misjudgements only reinforces the overall sense of immense ability and the undoubted ultimate success.

However we judge Caesar as a commander, the simple truth remains that he did keep winning, and that setbacks like Dyrrachium did not turn into catastrophic defeats. He never lost a war, and his ultimate failure was political, misreading the mood of the senators who conspired against him. The campaigns described in this book were all civil wars, with the exception of the Zela campaign and Alexandria, although there many of his opponents were former Roman soldiers in service of the Ptolemies. Civil war plagued Romes Republic from 88 to 31 BC, as it would later plague the Roman Empire from the 3rd century AD until the final collapse in the West in AD 476. The impact of these Roman against Roman clashes on the development of the army is rarely considered, so it is worth reminding ourselves that the last five years of Caesars life, and many of his hardest campaigns, were waged against armies led by men he knew well, following the same doctrines and tactics.