CAESARS

FOOTPRINTS

A CULTURAL EXCURSION TO ANCIENT FRANCE:

JOURNEYS THROUGH ROMAN GAUL

BIJAN OMRANI

To Sam, Cassian and Beatrix

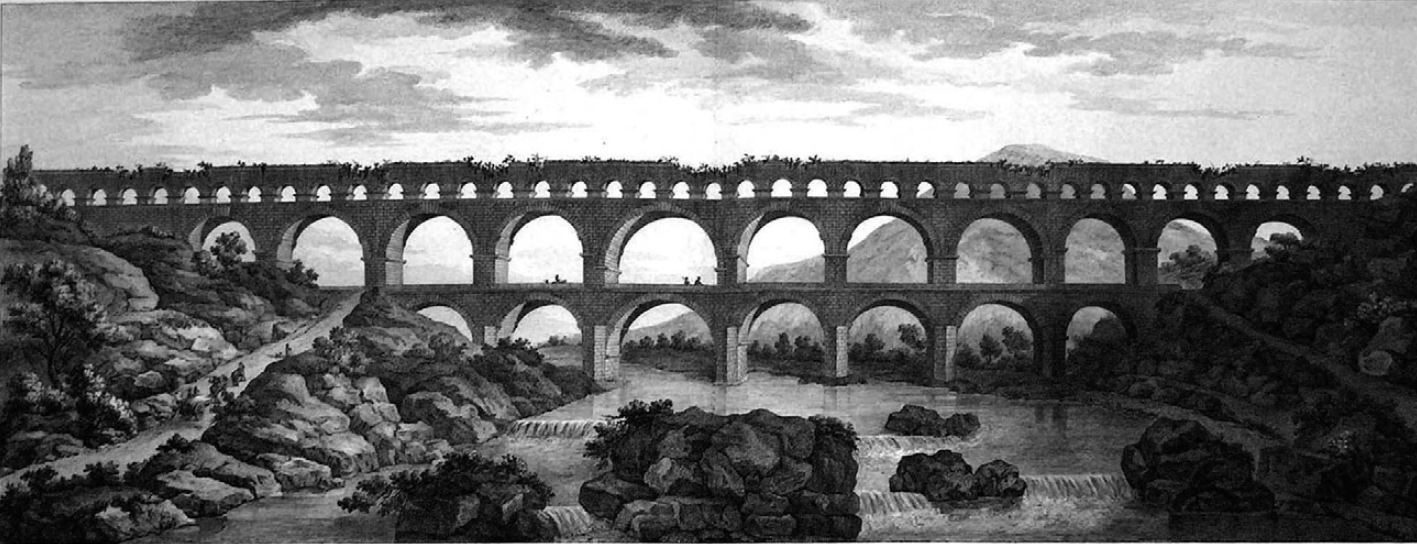

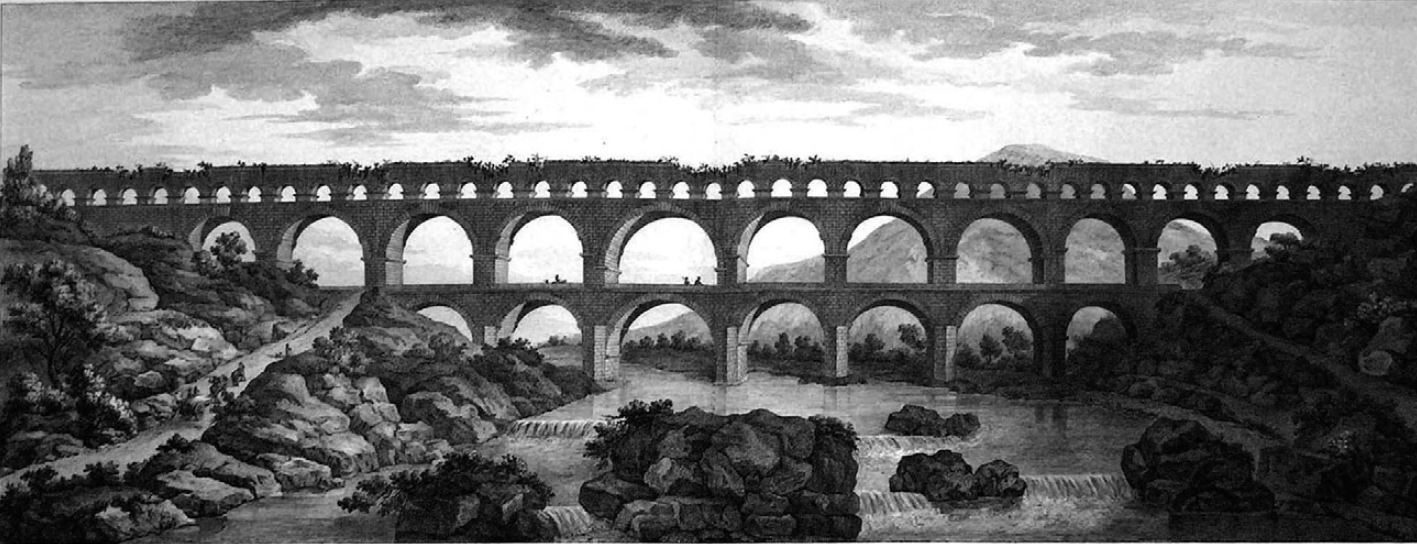

The Amphitheatre at Nmes. Like that of Arles, it was built around ad 70, and was converted into a fortification by the time of the Visigoths. It functioned as a town in its own right, until being restored to its more recognizably Roman form (and function), for bullfights and other public spectacles, in the mid-nineteenth century.

Page numbers listed correspond to the print edition of this book. You can use your devices search function to locate particular terms in the text.

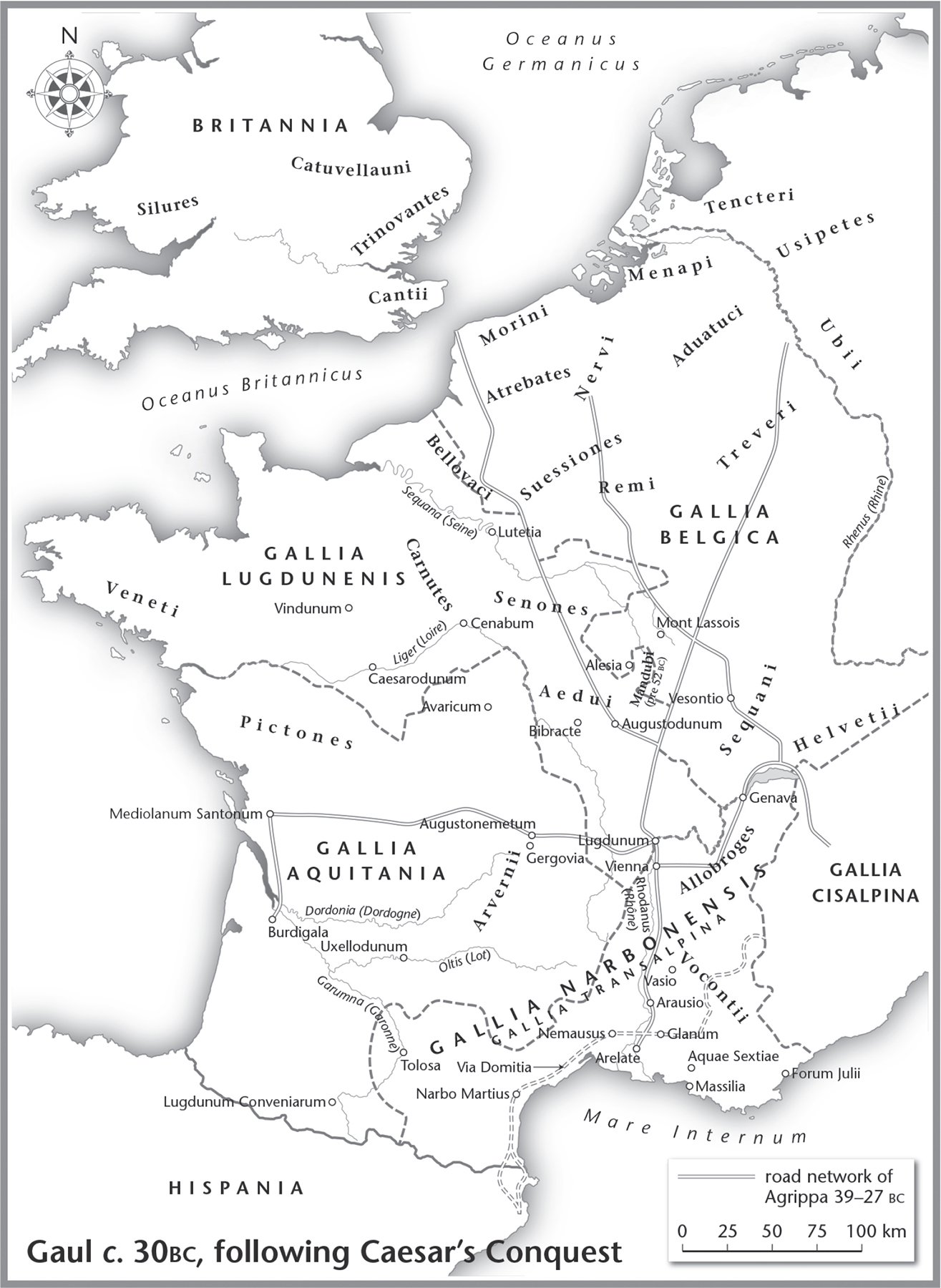

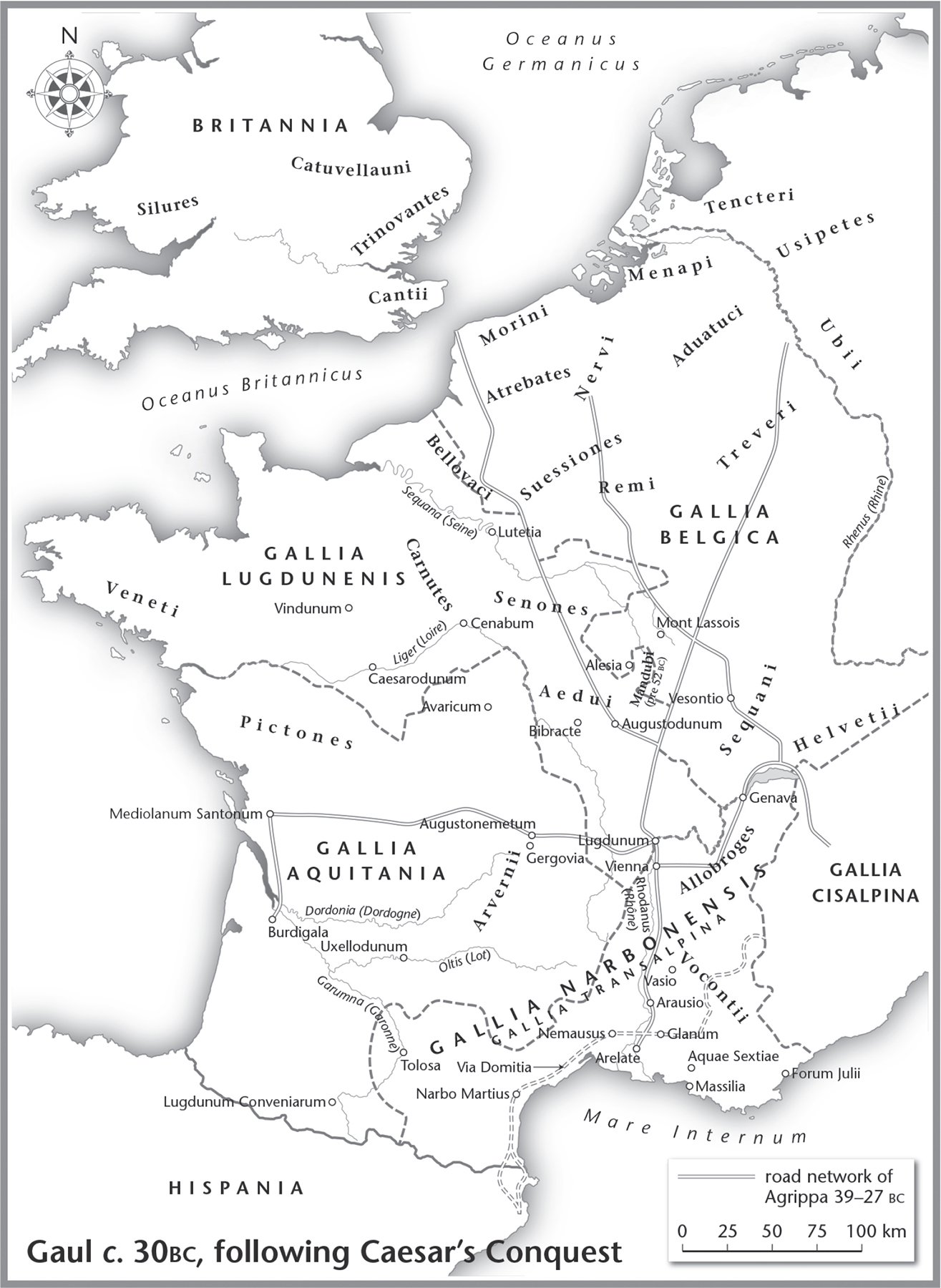

1 The tribes of Gaul at the time of Caesar

2 The course of the Rhne from Geneva to the Pas de Lcluse

3 The Battle of Bibracte

4 The Battle of Gergovia

5 The Battle of Alsia

6 Julius Caesars invasions of Britannia

Maps 25, together with the map that appears in the endpapers, were prepared by Colonel Stoffel in the 1860s during the archaeological investigations ordered by Napoleon III into the Gallic conquests of Caesar. They were first included in Napoleon IIIs Histoire de Jules Csar, published in 1866.

The use of the words Celtic, Gaul and Gallic caused considerable difficulty to classical authors, who could not agree on their exact meanings. There was a debate as to whether all Gauls were Celts, or whether they were mutually exclusive, and whether the term Gallic should be used to denote just those peoples living in the southern and western areas of modern-day France (as opposed to those who lived in the Belgic or Aquitanian regions). This difficulty exists as much for contemporary authors. For simplicity, I use the word Gauls to describe those people who lived in the area designated by Julius Caesar as Gaul.

Another challenge is the use of ancient and modern place names. Here, I make no great claims to consistency. In general, I have tended to use ancient place names when talking about the places in the Roman context. However, this is not always the case. For example, I have stuck with Autun rather than persistently using the lengthy ancient name of Augustodunum. Both ancient and modern names of places are given in the index for clarity.

CAESARS

FOOTPRINTS

T HE IDEA FOR WRITING THIS book came to me a few years ago, while I was teaching a Latin lesson. It was a Wednesday morning deep in the winter term, period two. I was conducting a Latin language session with a bright but not especially motivated lower sixth. The unfortunate fodder for this exercise was the fifth book of Julius Caesars Commentaries on the Gallic War, describing his conquest of Gaul between 58 and 50 BC.

There was something almost ritualized about the pupils misery during these sessions. The use of Caesar as fodder for teenage children to take their first steps in translating real Latin, after leaving behind the safety of language textbooks, is an ancient tradition. Say Caesar to anyone who has been subjected to an education containing a classical component, and there are two likely reactions. One the one hand, a cheerful reminiscence of how good Caesar was for them: how wonderfully hard his writing worked their brain, as if his dialogues were specifically designed like some formidable fibre-laced breakfast cereal to improve their cerebral motions. On the other, a cross-eyed stab of agony, like thinking back to a mental version of the Somme, where all was muddy quagmire and barbed-wire entanglements formed of indirect statements enmeshed with ablative absolutes and gerundives of obligation. My lower sixth form class was very much in the latter camp.

I hated it that, for generations of schoolchildren, this was the miserable end to which Caesars account of the Gallic Wars was put. During that lesson, as someone, floundering in a particularly long and vicious stretch of oratio obliqua, sixteenth centuries and very little likelihood that we would have been sitting in that classroom reading a classic work of Latin literature on a cold Wednesday morning.

I expressed myself largely and eloquently. My class essentially told me to sod off. Not one to give up on a fight with my students, I determined then that I would do something to save Caesar from the slough of grammar and syntactical misery to which he perhaps as fitting punishment from the Furies for the Olympian scale of his ambition had been condemned.

Modern interest in Caesar tends to concentrate on what he did in Rome rather than on what he did in Gaul. It is the political intrigue that marked his rise to prominence and his victory in the civil war, and the period that led up to his assassination, that captures the twenty-first-century imagination. His time in Gaul, and his bloody activities there, are by contrast relegated to the classroom, and the wretchedness of grammatical exercises for reluctant schoolchildren. My aim in writing this book is to redress the balance: to place centre stage what Caesar and the Romans who followed him achieved in Gaul, and to explore their lasting and highly visible cultural legacy.

The purpose of this book is not to give a military account of Caesars time in Gaul; nor, indeed, is it exclusively devoted to Caesar. There are many excellent works that already fill this niche. It is intended rather to examine the circumstances that led to the Roman conquest of Gaul, and to consider the reasons why, after the initial bloodletting of the Gallic Wars, it would prove to be such a long-term success: how the Roman transformation of Gaul laid the foundations of modern Europe. It therefore looks at the history of the engagement of Rome and Gaul and the cultural and economic impact of that connection. Physical evidence of this can still be seen on the ground, and parts of the book are devoted to the surviving vestiges of Roman Gaul amphitheatres, aqueducts, triumphal arches, temples and mausoleums. I will also trace the impact of Roman Gaul on cultural ideas, literary remains and religious traditions.

The question as to how Rome managed to knit Gaul to itself so effectively that it remained a part of the empire for half a millennium has an enduring relevance. In an age in which the aspiration for European unity looks increasingly chimerical despite the blessings of technology and the modern era, it is instructive to look back to when this ideal, under Rome, was first born, how it was brought about and what in the example of Gaul was its cost. It is tied up in questions not just of material change, but also culture, and in particular how Rome dealt with outsiders and migration. The Roman movement into Gaul was arguably born as a response to the first European migration crisis for which we possess an eye-witness account (however slanted it may be). To describe Caesar and the conquest of Gaul is also to describe how Rome treated the barbarian other. And this demands that we look at Caesar not just as a grammatical exercise, but as the brooding presence the vast ghost in the words of Lawrence Durrell that still hangs over a Europe which struggles to be at one.

Next page